Success Factors in Operational Performance of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) in Nigeria for Poverty Reduction

Samuel Taiwo Toluyemi1, *, Mubarak Sanni2, Temitope Titilayo Toluyemi3

1Department of Agricultural Development Management, Agricultural & Rural Management Training Institute (ARMTI), Ilorin, Nigeria

2Department of Accounting & Finance, College of Humanities, Management and Social Sciences, Kwara State University, Malete, Nigeria

3Department of Operations, Pension Alliance Limited (PAL), Lagos, Nigeria

Abstract

There is little evidence of research efforts into success factors in MSMEs in Africa. However, many research efforts have focused on constraints or challenges of MSMEs performance. No doubt these efforts have provided some insights into the understanding of the practice of entrepreneurship in Africa. However, they failed to provide adequate understanding of processes, mechanisms and procedures through which these factors influence performance of enterprises in Africa: This study therefore, attempts to bridge this gap by examining the extent at which some identified factors influence performance of enterprises in Nigeria. Appropriate descriptive statistics and Ordinary Least Square (OLS) regression analysis were used to describe and analyze the data collected. The study revealed that the age at which a potential entrepreneur starts apprenticeship, entrepreneur’s level of education, family type of entrepreneur and the enterprise start-up arrangement have negative relationship with the performance of enterprises. On the other hand, period of apprenticeship, backward, forward and horizontal networkings have positive relationship with the level of performance of enterprises. However, only forward networking is significant at 1% level of significance while backward networking and family type are significant at 5% level of significance. In the same vein enterprise location is significant at 10% level of significance. The study recommended that the Nigerian Educational Curriculum be amended to include entrepreneurial development right from the primary school to the tertiary level. Similarly, Government at all levels should embark on empowerment programmes for youth to encourage them to get attached to a master trainer for mentoring. The master trainers should be given incentives based on the number of their mentees. However, at the end of the mentoring, professional certification should be given to successful participants. This certification will enable them to approach any designated financial institution with a bankable proposal for funding. In addition the study also recommends enhancement of Value Chain Development skills and processes especially for agricultural produce. The study also recommends further research to be made into success factors on industry and sector basis as each industry and sector are unique.

Keywords

Success Factors, Performance Entrepreneurship, Micro, Small and Medium, Enterprises (MSMEs)

Received:May 24, 2016

Accepted: June 4, 2016

Published online: September 23, 2016

@ 2016 The Authors. Published by American Institute of Science. This Open Access article is under the CC BY license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

1. Introduction

Nigeria is an African country that is populated with about 170 million people making it the most populous African nation. It accounts for between 10 to 15 percent of African population. About 60% of these population live in rural areas. The country is endowed with rich human and material and financial resources. For instance it is the eight world largest exporter of crude oil is blessed with. The country is also blessed with wide arable land and is also very rich in other solid minerals such as iron ore, tin, columbite etc.

However, Nigeria is scored very low in terms of economic and social progress. For example, Human Development Index (HDI) which measures development in terms of life expectancy, Educational enrolment and income rated Nigeria as number 158 out of 182 countries of the world (UNDP [31]. Indeed it lags behind some smaller African nations such as Kenya, Pakistan, Angola and Tanzania in terms of economic development. Similarly, more than 50% of Nigeria live on less than one dollar a day. The unemployment rate in the country reached 10.6 percent in 2012.

1.1. Role of Entrepreneurship in National Development

A general belief by researchers, development practitioners and agents is that a robust Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) must be the bedrock of an inclusive and sustainable development. Indeed a significant characteristic of developed and emerging economies is a booming and blooming MSMEs. (Toluyemi et al [29], Eniola, [7], and Ogbo and Agu [17]. Therefore, MSMEs sector is a driving force and mainstay of economic growth of most developed and emerging economies of the world. It is the harbinger and catalyst of positive economic change. MSMEs play significant role in growth, development and industrialization of many countries. However, the contribution of MSMEs varies with the different sectors and level of economic development Onuba [19].

Beck et al [2] cited UNIDO that Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) consist of 90% of all enterprises in the world and on the average, are accountable for 50 to 60 percent of total employment. In the whole of Asia and the pacific more than 95% of companies are SMEs, Japan 99%, Singapore, 99.7% and in Malaysia 96%. SMEs account for 75% Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in Uganda and 40% GDP of Kenya. SMEDAN [26] observed that MSMEs are about 96% of Nigerian enterprises.

An important reason for encouraging MSMEs is employment generation. It is estimated that MSMEs has higher propensity to generate employment per capita or Naira investment than large scale enterprises. Most MSMEs employ mainly indigenous people and people at the lower half of the income distribution. Hence, it brings about inclusive development and more equitable distribution of income. UNCTAD [30] observed that the countries that have high number of MSMEs have more equitable distribution of income regionally and equitably. Consequently, it leads to improved standard of living and reduce the gap between rural and urban development. This assists in reducing rural urban migration and inequalities. Hence, MSMEs contribute significantly to poverty reduction in any economy.

Following from the experience of the large scale enterprises in both developed and emerging economies they transited from small scale to large scale. Hence, the MSMEs are large scale enterprises in the embryo if given conducive environment to thrive. In addition, MSMEs also produce intermediate and final goods for the large enterprises and the economy as a whole. Indeed large companies sub-contract their components to MSMEs rather than competing with them. Hence, it provides for both forward and backward integration which is a sine qua non for a sustainable development. As a result of the above any discourse on economic growth in the developing economies always has development of MSMEs in the front burner.

In spite of the general consensus about the contributions of MSMEs to economic growth and development, empirical evidence to support this position is rather weak and inconclusive. For instance Institutional Reform and Informal Sector (IRIS) commissioned by USAID and cited by Mwangi et al [13] limited correlation between economic growth and number of SMEs. Similarly, there were inconclusive links between medium enterprises and economic growth. In the same vein there is no significant connection with micro and small enterprises and economic growth (Mwangi) [13].

Studies such as Back et al [2] observed a strong association between relative size of SMEs and GDP per capita but no strong evidence that SMEs alleviate poverty or reduce income disparities. It is important here to note that studies that attempts to link MSMEs to national growth and development are few. In addition such studies have questionable definitions and methodology. For instances operational definition of SMEs varies from country to country. IRIS study measure SMEs solely by number of employees. The study also relied on static data which has a limited application in regression analysis. Therefore, the results of such studies are likely to have limited application. As a result of these realities we can tentatively conclude that the lack of casual link does not necessarily imply that such linkage does not exist. However there is substantial evidence to show that successful enterprises are germane to economic growth and development because of its wealth creation and employment generation abilities. However, based on these criteria, Nigerian enterprises are scored very low. This is attributed to poor attitude and habits, skills deficiencies, environmental factors including policies and infrastructural decay.

A concerted effort at improving entrepreneurial activities in the country started in 1972 with the indigenization law i.e Nigerian enterprises policy. Since then succeeding governments in Nigeria have made efforts at improving entrepreneurship in Nigeria. These efforts range from provision of infrastructure, employment generation policy/guideline, provision of funds for MSMEs. In most cases, government efforts led to establishment of institutions such as Directorate of Food, Road and Rural Infrastructure (DFRRI) 1986, National Directorate of Employment, (NDE) 1986, Agricultural Credit Guarantee Scheme Fund, (ACCSF) 1977, National Industrial Policy 1988, Micro-Finance Bank Policy 2004, Small and Medium Enterprises Development Agency (SMEDAN) 2003, Bank of Agriculture (BOA) 1973, Bank of Industry (BOI) 2001, Small and Medium Enterprises Equity Investment Scheme (SMEEIS) 1999 which is the bankers forum initiative, Raw Material Development Council (RMRDC) 1987. Etc.

However, the performance of MSMEs has been affected by low level of entrepreneurial orientation. In addition most business owners have high technical skills but have very low management and entrepreneurial skills. The managerial skills that are majorly inadequate include; time management, communication, human resources, marketing, financial management as well as business ethics, social responsibility, leadership and decision making Oyeku et al [24], Blossom et al [3] and Eniola [7].

The mortality rate of MSMEs is very high in its first five years. Agbo and Agu 2012 attributed this to a lack of clear vision and mission by entrepreneurs. Hence they are easily blown away by intense competition as well as harsh business environment.

Similarly, Odii and Njoku [16] observed that majority of those that ventured into MSMEs do so because of their need to make money. Hence in most cases such entrepreneurs lack relevant and adequate information about the business. Therefore in case of any problem they lack adequate problem solving skills. Hence, they find it difficult to survive any turbulent business season(s).

In spite of the huge financial and human resources that are invested in entrepreneurship in Nigeria, the results have been considerably low. Some reasons attributed to this is inadequate and untimely release of funds, engagement of unqualified and incompetent staff, in some cases staff are engaged on the basis of their political affiliation and willingness to manage the agencies for the benefits of their sponsors to the detriment of the nation. Hence, loans and facilities are granted to politicians, relations and friends who may not have any business outfit. Such beneficiaries see the facility as their own share of the national cake or reward for their political patronage and loyalty (Odii and Njoku [16].

1.2. Constraints to Entrepreneurship in Nigeria

Several reasons have been adduced for the poor performance of MSMEs in Nigeria. Toluyemi et al [29] classified the challenges of MSMEs into three namely: demand side, supply side as well as government regulation/policies and institutional supports.

(a) Supply side refers to constraints that affect all requirement/inputs for the enterprises to achieve its missions. This include:

(i) Inadequate Human Resources in terms of quality and attitude – Poor managerial and technical skills including planning, leadership and Information and Communication Technology (ICT) skills;

(ii) Inadequate Flow of Financial Resources – This refers to poor access to affordable long and short term funds as well as discrimination against MSMEs by banks;

(iii) Poor Access to Technology – This include poor access to research and technology;

(iv) Infrastructural decay including non-functional, absence or deteriorating infrastructural facilities such as transport, water, electricity security etc.

(b) Demand side refers to market and marketing risks such as:

(i) Poor market and marketing including harsh competition;

(ii) Cultural hindrances including gender discrimination as well as ethnic and religious intolerance;

(iii) Poor networking i.e. backward, forward and horizontal linkages or networking;

(iv) Poor entrepreneurial attitude – Many young potential and existing entrepreneurs see entrepreneurship as a means to eke out a living or make money Odii and Njoku [16]. Most of them are ill prepared for the tasks of entrepreneurship because they are in a hurry to make money.

(c) Government regulations/policies and institutional supports. This include:

(i) Multiple taxation, inconsistent government policies, political upheaval which results from ethnic intolerance.

(ii) Wide-spread corruption and greed which makes procurement of licenses, permits, goods and services from government agencies costly, cumbersome and time consuming.

In addition Bowen et al [4] identify competition, insecurity, poor debt collection, lack of working capital and power interruption as the five top challenges of MSMEs.

1.3. Statement of Problem

In spite of the fact that MSMEs constitute over 90% of the enterprises in Nigeria its contributions to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), employment generation and income distribution is nothing to write home about. For instance, Eniola [7] and SMEDAN [26] observed that MSMEs sector contributes between 5% to 40% of the GDP in Nigeria. Therefore all the efforts of succeeding governments, developing partners at evolving programmes and policies that will harness the nation’s abundant resources via MSMEs promotion to engender economic development has not yielded the desired result.

In addition, Toluyemi et al [29] observed that the growth rate of enterprise is slower than that of the population growth while the existing MSMEs are collapsing Tarus and Nganga [27] opined that 60 per cent of SMEs close down within the first year while 40 per cent of those that survive the first year are likely to close down in the second year. Smit and Watkins [25] and Mead and Liedholm [12]) observed that more MSMEs close down than those that expand and that only 1 percent grow from five to 10 employees. Indeed, it was said that a significant number of MSMEs are survivalist enterprises with no signs of growth.

Oyeku et al [24] observed that very little attention is paid to research on entrepreneurial success in spite of the increasing challenges of business failures often times orchestrated and accelerated by harsh business environment. Indeed most African studies tend to focus on causes of failure of MSMEs and less on success factors. No doubt this approach offers some useful insight into the state of MSMEs sector across various regions of Africa but hardly reveals the mechanism and process through which factors influence the enterprise success.

1.4. Conceptual Framework

Successful enterprises are germane for national economic development because of its wealth creation and employment generation abilities. However, based on these criteria, Nigerian enterprises have been rated low. Performance of MSMEs has been variously looked at or measured from different perspectives. Islam et al [11] looked at enterprise performance as ability to create an acceptable financial outcome such as profitability or income generation level. This is often measured in quantitative terms with indices such as Return on Assets (ROA), Return on Investment (ROI), Sales/Turnover, Net Profit etc. On the other hand, Owoseni and Akanbi [20] looked at a successful enterprise as a function of financial and non-financial variables. Non- financial variables are measured in qualitative terms. They include knowledge and business experience, ability to develop and offer quality products and services, ability to manage and work in group, labour productivity and corporate responsibility.

ENSR [8] and Coad 6] defined successful enterprises as those that survive the first five years of existence especially those that adapts more effectively and take advantage of the opportunities offered. Other authors that see enterprise as a mirror of societal values of the domiciled localities believed that SMEs success should be in alignment with the local management practices.

Entrepreneurial success factors have been looked at on country basis. For example Jordanian SMEs success factor is said to include technical procedures and technology, firm structure, financial structure, marketing, productivity and human resources structure. On the other hand, Malaysian SMEs success factors are based on personal initiative, education, working experience, managerial and technical skills and parent’s involvement (Mwangi et al [13]. However, studies conducted in many African Countries link enterprise success to entrepreneurial orientation, personal initiatives, strategy and formalization of enterprise status (Bowen et al [4], Oyeku et al [27] and Eniola [7].

Generally, measure of enterprise success can be classified into three namely:

(i) Performance denominated measures e.g. profits, turnover, number of employees etc.

(ii) Survival and sustainability factors such as enterprise age

(iii) Non qualitative measures such as satisfaction and reputation.

1.5. Objectives of the Study

As a result of the popular support for the important role MSMEs could play in national development, it is germane to understand the success factor in MSMEs. Therefore, this study examined the relative importance of some success factors in the performance of MSMEs as catalyst of national development in Nigeria. Attempt was also made to identify some constraints militating against effective application of these success factors with a view to proffering practical solutions to constraints identified.

1.6. Meaning of Some Terms

1.6.1. Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs)

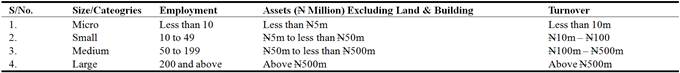

Are defined differently by different authors and countries of the world. However, a common ground seems to be that they all look at it from both number of employment generated, total assets or capital investment and sometimes annual turnover/sales (Zimerer [32]). In Nigeria MSMEs are defined by various programmes such as SMEEIS, Nigeria Ministry of Commerce and Industry (2003); Operational Guidelines of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises and National Policy on MSMEs which adopted SMEDAN definition. This study also adopted the SMEDAN definition because it is more current and comprehensive. (Toluyemi, et al [29]).

Micro enterprises are enterprises that have less than N5 million assets minus land and buildings and also employ less than ten (10) people as well as having less than N10 million turnover per annum. On the other hand, small enterprises have at least N5 million but not up to N50 million assets minus land and building as well as employ between ten (10) and forty nine (49) people. In addition it has between N10 million and N100 million turnover annually. Medium enterprises have at least N50 million but less than N500 million assets minus land and building as well as employ between fifty (50) and one hundred and ninety nine people. It also has between N100 million and N500 million turnover annually. See table 1 for details. In case of conflict between assets and employment criteria, the employment criterion takes precedence.

Table 1. Msmes in Nigeria.

Source: National Policy on MSMEs 2010 as quoted in Survey Report on Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) in Nigeria (2012).

1.6.2. Performance of MSMEs

Based on National Economic Empowerment Strategies (NEEDS) NPC [14]) and Literature such as Owualah [21] and Onwumere [22]) identification of indicators of economic growth and poverty reduction, this study measured enterprise success by the following criteria namely;

(i) Wealth creation/profitability

Sustainability/number of years of existence of enterprises. Employment generation/number of people employed.

(ii) Distribution of income.

The study, however, assumed that if the first two criteria (i and ii) are effectively achieved, the last two (iii and iv) will automatically be achieved. Hence, performance of an enterprise is proxied by the product of its profit and sustainability index. This is justified by the research findings that indicated that only about 20 percent of enterprises live to see their fifth anniversary (Tarus and Nganga [27] and Toluyemi et al [29]). The sustainability index is categorized into five and measured as follows; Enterprises in existence for 1-5 years are scored 1; 6-10 years 2; 11-15 years 3; 16-20 years 4; and 21 years and above 5. Subsequently, the following index were allocated 1/5, 2/5, 3/5, 4/4 and 5/5 to 1-5 years, 5-10 years, 11-15 years, 16-20 years and 21 years respectively.

2. Methodology

2.1. Model Specification

The model is structured to ascertain the extent to which the identified factors affected the performance of the enterprises. The model is expressed as follows:

Y=![]() o+ß1ApprAge1+ß2LenAppr2+ß3EE3+ß4 FamTyp4+ß5NetFor5+ß6NetBac6+ß7

o+ß1ApprAge1+ß2LenAppr2+ß3EE3+ß4 FamTyp4+ß5NetFor5+ß6NetBac6+ß7

![]() (1)

(1)

Where;

Y = Performance Index of MSMEs, ApprAge = Apprenticeship age, LenAppr = Period/Length of Apprenticeship, EE = Entrepreneurs’ Level of Education, FamTyp = Family Type, NetFor = Forward Networking, NetBac = Backward Networking, NetHon = Horizontal Networking, StatUp = Entrepreneur Start Up, EntLoc = Enterprise Location.

2.2. Data Collection

Primary data were collected through structured questionnaires and interviews. These instruments were used to elicit information on success factors in entrepreneurial practice in Nigeria. Respondents were requested to respond to some issues on the identified success factors. These identified success factors were chosen based on observation of characteristics of successful enterprises in Nigeria. Unstructured interviews were held with fifty of the respondents to ensure validity and reliability of their responses. Three hundred entrepreneurs were randomly sampled from twelve states out of 36 states of Nigeria. In order words two states were randomly chosen from each of the six geopolitical zones of the country.

2.3. Method of Analysis

The study applied descriptive statistics techniques such as mean/averages, percentages to describe some characteristics/phenomenon of the success factors. In addition Ordinary Least Square (OLS) technique is applied to examine the extent to which the identified success factors contribute to the performance of MSMEs in Nigeria.

3. Data Analysis and Findings

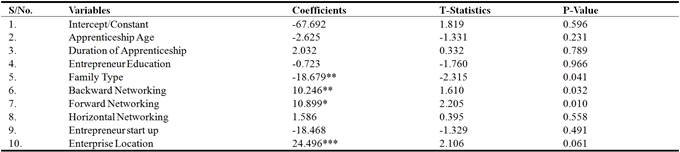

The regression model is formulated to have some insight into the extent to which the identified success factors impacts on the performance of enterprises in Nigeria. Nine success factors were identified namely; apprenticeship age, period or duration of apprenticeship, Entrepreneur level of education, Family type, Backward, Forward, and Horizontal networking, Entrepreneurs’ start-up arrangement and Enterprise Location.

The regression model indicated that the success factors identified adequately explained the variation in the performances of MSMEs in Nigeria (R2 = 0.882 coefficient of determination) i.e. the explanatory variables explains 88.2% the variation in the independent variable (the performance index). The regression model is significant 1% level of significance. Hence, we can conclude that the identified success factors contribute significantly to the performance of enterprises in Nigeria.

3.1. Apprenticeship Age

Majority of the respondents do not serve apprenticeship. Precisely 53 percent of them said they do not serve as apprentice under anybody. Most of those that serve apprenticeship are artisans. Indeed the educated entrepreneurs hardly served apprenticeship.

The ages that a potential entrepreneur starts his apprenticeship training have impacts on his ability to imbibe some of the essentials discipline and entrepreneurial characteristics. For instance the younger the trainees the higher their ability to imbibe the required entrepreneurial characteristics. About 6 percent of the respondents started apprenticeship 16 and 25 years of age. Only 19 percent started at about 25 years and 20 percent started at age less or equal to 15 years. The apprenticeship age of the trainee is negatively related to the performance of the enterprise (Coefficient is -2.265) in other words the younger the age of an entrepreneur when he/she starts entrepreneurship training the better the performance of the entrepreneur. However, it is not significant. This may not be unconnected with the fact the at younger age one can learn faster and are amendable to discipline that entrepreneurship requires.

3.2. Duration / Period of Apprenticeship

This refers to the period with which a potential trainee stays with a mentor for mentoring. The period of apprenticeship is the period in which the entrepreneur acquires skills including psychological and emotional attitude to cope with the task of entrepreneurial activities. The period ranges between six months to about seven years. The longer the duration the higher will the ability to learn the psychological, emotional, attitudinal, managerial and technical skills be. Indeed, the longer the period, the more the understanding of the industry’s terrains. Respondents’ response indicated that about 40%, 35% and 25% of the people served apprenticeship for less than two years, four years and above four years respectively.

In most cases many people especially the educated ones believe that you can start any business without undergoing some period of mentorship so long as you have your money. No wonder some businesses collapse when they face some challenges in the business due to inadequate information and understanding of the industry. The model indicated that duration or period of apprenticeship is positively related to enterprise performance (coefficient is 2.032). This is to say that the longer the period of apprenticeship the higher the performance. However, it is not significant. The period of apprenticeship exposes the entrepreneur to different hazards and decision situations. Hence, the longer a person stays as apprentice, the more he/she understands the market and the workings of the industry.

3.3. Entrepreneur Level of Education

No doubt education prepares one with the intellectual and emotional ability to cope with the task of life. Therefore, it is expected that the higher the level of education the higher the chances of success in any chosen career. Majority of MSMEs entrepreneurs have maximum of Senior School Certificate (SSE). Precisely 38.4% are said to have maximum of Senior School Certificate. On the other hand, 30.9% of MSMEs’ entrepreneurs have degree while only 9.3% had post graduate degree. The regression model indicated that level of education of the entrepreneur is negatively related to the performance of the enterprise. (Coefficient is -16.723) However, it is not significant. In other words the lower the level of education the higher the performance of the enterprises. The reason may not be unconnected with the fact that the less educated people see entrepreneurship as their last hope of means of livelihood whereas the educated ones have alternatives. Hence, the less educated people put in the whole of their being into the business. In addition, most of the educated people want to start a relatively big enterprise. Hence, the learning curve is truncated with little or no cognate experience.

3.4. Family Type

The African culture including religion allows men to marry more than one wife. This also translates into large family size. Hence, a man with more than one wife will have a larger family. Therefore, most family businesses are often over whelmed by the demands on returns from the enterprise. Polygamy and large family size also has implications on the family cohesion and unity which affects the family support for the enterprises. The situation gets worsened after the demise of the promoter of the business. This affects the sustainability of the business. Therefore, in some cases some enterprises do not out-live their promoters because of family internal wranglings and poor succession planning. Responses of respondents indicated that about 70% are married. However, about 43% have only one wife while about 57% have more than one wife.

Regression analysis result indicated that the number of wives of the entrepreneur has negative relationship with the performance of the enterprise (Coefficient is -18.679). This is to say that the lower the number of wives of an entrepreneur the higher the performance of their enterprise. This is significant at 5% level of significance. The monogamous family business has a higher potential to be sustainable because members of the family have higher sense of belonging and ownership. Hence, succession planning is practicable.

3.5. Networking

Networking refers to ability to have a working relationship with enterprises that provides inputs, market or at the same level of production. Hence, networking can be classified into three namely: forward, backward and horizontal networking.

3.5.1. Backward Networking

Backward networking refers to having relationship with firms that supply inputs for the enterprises. This enables the firm to have a firm grips on its input supply. Responses from respondents indicated that 19.2%, 29% and 42% have backward networking always, often and sometimes respectively. Only 9.8% hardly have backward networking. The regression analysis showed that backward networking has a positive relationship with performance of the enterprise (Coefficient is 10.246). This is to say that the higher the backward networking the higher the performance of the enterprise. This is however not significant. Relationship with source of supply guarantees constant and quality supply of goods and services to the enterprise.

3.5.2. Forward Networking

On the other hand forward networking is having relationship with enterprises that buys the enterprise output. Therefore it allows for a significant influence in the market. Responses of respondents indicate that 35%, 37% and 20% has forward networking always, often, sometimes respectively. However, 12% hardly have forward networking. The model indicated that forward networking has a positive relationship with performance of enterprises (coefficient is 10.899) in other words forward networking has positive impact on the performance of the enterprises. It is significant at 5% level of significance. A robust relationship with the market guarantees price for the organization. Therefore, the enterprise becomes more profitable.

3.5.3. Horizontal Networking

Horizontal networking refers to linkages with enterprises operating at the same level. Hence, it allows for a joint efforts and action to enable them share experiences and speak with one voice on issues of common interest. Responses from respondents show that 21%, 29.4% and 37% have horizontal networking always, often and sometimes respectively. Only 10.6% hardly have horizontal networking. Horizontal networking commonly referred to as joining of association ensures experience sharing and ability to speak with one voice on issues concerning their enterprise. Hence the have firm control of the market, inputs etc. This assists them to be more profitable.

The regression analysis showed that horizontal networking has a positive impact on performance of enterprises, (coefficient is 1.586). This shows that the higher the horizontal networking the better the performance of the enterprise. This is however, not significant.

3.6. Enterprises/Entrepreneurs Start-up Arrangement

This refers to the arrangement that is put in place for a trainee/mentee to start his/her enterprises. In some cases the mentor/trainer has the responsibility to start-up his mentee on his own enterprise. On the other hands there are other plans that the enterprises is outside the training or mentoring arrangement. This includes that which after training the trainee finds a way to start on his own or with the support of family members and relations. In some cases trainees approach financial institutions for support. Responses of respondents show that 22%, 13%, 35% and 28% were set up by Master Trainers, spouses, self and parents and relations respectively. Only 2% were set up by financial institutions. In the same vein the source of start-up capital are 21%, 24% 21% and 9% from Master Trainers, Personal savings, parents and relations respectively. In addition 25% of the start-up funds come from cooperative societies.

The model indicated that the start-up arrangement has negative relationship with performance of the enterprise. In other words the more the start up is not at the mercies of relations the better the enterprise. This is however not significant. This may be explained by the fact that if relations such as spouse (husband and wife), parent’s relations etc provide the start up arrangement the entrepreneur may not consider implication of failure as grievous. However, if such arrangement is made by external party such as master trainer, banks etc the entrepreneur considers implication of failure of the enterprise as very serious. This has a lot of implications on the level of seriousness of the entrepreneur.

3.7. Location of Enterprises

The location of the MSMEs is classified and allocated the following figure Urban Central Business District (CBD) 4, Urban suburb 3, Rural Central Business District 2 and Rural Suburb 1 (Toluyemi and Samuel [28]).

Location of MSMEs has implications on their costs and returns. Generally the overhead cost and indeed turnover in the urban centres are higher than those in the rural areas. The regression analysis revealed that there is a positive relationship with the performance of the enterprises (coefficient is 24.496). It is significant at 10% level of significance. This means that MSMEs in the urban centre perform better than those in the rural areas. This can be explained by the fact that enterprises in the urban centre are nearer to market and they enjoy better public facilities/amenities.

From the above it is clear that Apprenticeship age, Entrepreneurs’ level of education Family type, Entrepreneurs’ start-up arrangement have inverse relationship with enterprise performance. On the other hands Period/duration of apprenticeship, Backward, forward and horizontal networking as well as Enterprise location have positive relationship with enterprise performance.

The analysis showed that Family type (i.e. monogamy or polygamy), forward and backward networking as well as enterprise location significantly enhanced operational performance of enterprises in Nigeria. However the impact of apprenticeship age, period of apprenticeship, entrepreneurs’ level of education, horizontal networking as well as enterprise start-up arrangement have no significant impact on enterprise performance.

Table 2. Regression statistics for the model of the study.

Multiple R = 0.939

R square = 0.882

Adjusted R2 = 0.797

Standard Error = 24.518

Significance F =0.0004

Source: Computer print out from data analysis 2016

* 1% level of significance

** 5% level of significance

***10% level of significance

4. Discussions of Findins and Conclusions

Findings point to the fact that the identified success factors adequately explain the variation in the performance of MSMEs in Nigeria. For instance, the R2 or coefficient of determination explains the variation in performance by about 88.2%. Nine success factors were identified. However, the study revealed that period of apprenticeship; forward, backward and horizontal networking as well as enterprise location have positive relationship with performance of enterprises. On the other hand, age at which apprentice started apprenticeship, Entrepreneur level of education, Family type and enterprise start up arrangement have negative relationships with the enterprise performance.

African culture and religion supports polygamy. However, problem of disunity and lack of cohesion are prevalence in most polygamous homes. Consequently after the demise of a successful entrepreneur, his enterprise dies with him. This is because his children, wives and relations will not be able to sustain the enterprise. Therefore, most enterprises hardly out-live their promoters especially polygamous promoters. The results of this study indicated that entrepreneurs that have monogamous families promote better performed enterprises because of the better family support that he/she enjoyed. This conclusion agrees with the assertion of Mwangi et al [13].

The common saying that experience is the best teacher aptly describes the results of this study. It revealed that promoters that served apprenticeship promote better performed enterprises. In addition, it also indicated that promoters that served longer period of apprenticeship and at younger age have better performed enterprises. The reason for this observation may not be unconnected with their entrepreneurial cognate experiences and the fact that they have imbibed entrepreneurial attitude. This is supported by Toluyemi et al [29] which rated problem of poor entrepreneurial attitude very high among constraints to entrepreneurial development. Cognate experience of the industry in which they operate enables entrepreneur to navigate better challenging and turbulent periods in the in the life of the business.

The study also revealed that entrepreneurs’ knowledge is very important but not necessarily academic attainment. Hence, the results show that people with lower academic level of education promote better performed enterprises. This is because people with lower academic education have high knowledge, information and experience about the industry in which they operate because of their practical experiences on the Field.

In addition, they have also built enough shock absorber and resilience to cope with turbulent periods. This is possible because they have imbibed entrepreneurial attitude during period of apprenticeship. Therefore, they have better skills in managing turbulent periods.

The result of the study also revealed that family type and backward networking are significant at 5% level of significance. Similarly, forward networking and enterprise location are significant at 1% and 10% respectively. Hence, networking skills and arrangements are very important for the performance of enterprises in Nigeria. This assists in ensuring constant supply of inputs and also helps in marketing the products. In the same vein, family unity and support assist in building a successful enterprise.

The study also revealed that the enterprise start-up arrangement that is part of the mentoring or training scheme works better. This is because; the mentee or trainee is motivated by the enterprise start-up arrangement. Hence, he puts in his best into the learning and imbibing the knowledge, skills and attitude required to be successful in the enterprise.

In conclusion this study aligned with the earlier studies such as Beck et al [2], Owualah [21], Onwumere [22] and Eniola [7] that enterprise development plays a significant role in achieving an inclusive national development. This is done through wealth creation, employment generation and skills development for people at the lower end of income distribution in the society. Therefore governments and development agents need to develop strategies to enhance the development of the nine identified success factors especially networking. In addition there should be provision of affordable long and short term funds. A good mentoring scheme should also be put in place.

Recommendations

Based on the survey findings and the literature, we proposed the following processes and strategies.

The Nigerian educational curriculum should be amended to include entrepreneurial development right from the Primary School to the tertiary level. Similarly, government at all levels should embark on youth empowerment programme which will involve attachment to master trainers or mentors for proper mentoring. The vocational centres that are being established all over the country should be structured in such a way that participants will be given vocational and managerial knowledge and skills as well as entrepreneurial knowledge at the centre. However, the mentoring will be done by the master trainers. The master trainers should be given incentives based on the number of their mentees. However, at the end of the mentoring programme, a professional certification should be given to successful participants. This should qualify them to approach appropriate financial institution with a bankable proposal for funding.

In addition, the MSMEs should be encouraged to form Professional associations and networks. This is very important in ensuring uninterrupted supply of inputs as well as assessing markets especially exports markets which might be relatively difficult for individual entrepreneur working alone. It is often said that there is a poor Value Chain Development (VCD) especially in agricultural enterprises. Hence this study recommends that skills processes and education in agricultural VCD should be encouraged A good VCD will no doubt go a long way in enhancing the performance of enterprises in Nigeria. Hence, governments at all levels and Development Agents should encourage VCD education in the country. Indeed development of networking system is very important because most (57%) of Nigerian businesses are sole proprietorship and stand alone businesses.

It must be made known that the researchers in this study believed that each enterprise has unique and peculiar combination of success factors in different industry and different sectors. Hence, another research work should focus on critical success factors on industry and sectoral basis.

The focus of this study is on successes of enterprises rather than their failures. Hence, it gives insight on their successes rather than the gloomy picture of failure. It also gives the encouragement that it can be done. Hence, there is hope for the Nigerian MSMEs given the right atmosphere.

References

- Abiola Babajide, (2012) "Effects of Micro Finance on Micro and Small Enterprises Growth in Nigeria". Asian Economic and Financial Review Vol. 2, No. 4 PP 2-16.

- Beck T, Demirguc-Kurt A, and Ross L (2003)" The impact of Growth, Development and Poverty: Cross Country Evidence" Washington D. C World Bank."

- Blossom C, Aslam N, Said A. I. Amiri (2014) "Challenges and Barriers Encountered by the SMEs owners in Muscat" European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org).

- Bowen M, Morara M and Mureithi (2009)" Management of Business Challenges among Small and Micro Enterprises in Nairobi Kenya" KCA Journal of Business Management Vol. 2. Issue 1.

- CBN (2014) Central Bank of Nigeria Annual Economic Report.

- Coad, A (2007) "Firm Growth: A Survey’ Max Plank Institute Economics. Available in http://harchives-overtes.fr/ha/shs 00155762/

- Eniola A. A, (2014) "The role of SMEs performance in Nigeria" Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review (OMAN Chapter) Vol. 3 No. 12 pp 33-47.

- ENSR (2003) "Observatory of European SMEs. European Commission. Available in http://eu.europa.eu/enterprises,Policies/sme/facts-figures-analysis/smeobservatory/index-htm.

- Ibbih J. M. (2005) "New Partnership for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) "International Journal for Economic and Development Issues Vol. 5, No. 1&2.

- International Finance Corporation (IFC) (2011) "SMEs Conference IFC Africa "SME Banking Conference 2011 IFC Johannesburg.

- Islam M. A, Khan, M. A, Obaidullah, AZM, and Alam, M. S (20011) Effects of Entrepreneur and Firm Characteristics on the Business Success of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Bangladesh, International Journal of Business and Management 6 (3) 289-299.

- Meed D C, and Liedholm (1998) "The Dynamics of Small and Micro Enterprises in Developing Countries" World Development. 26 (1) 61–74.

- Mwangi R. M, Sejjaaka S, Canney S, Maina R and Kairo D, Rotich A, Owino E, Nsereke I, and Mindra R (2013) "Constructs of Successful Sustainable Leadership in East Africa" Trust Africa IDRC CRDI Investment Climate and Business Environment Research Fund (ICBE-RF Research Report No 79/13.

- National Planning Commission (NPC) (2004) "Nigeria: National Economic Empowerment Development Strategy (NEEDS).

- Obitoyo, K. M (2001) Creating Enabling Environment for Small Scale Industries Bullion Publication of CBN Vol. 25 (3).

- Odii O. A. I. A, and Njoku A: C (2013) "Challenges and Prospects of Entrepreneurship in Nigeria" Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies MCSER-CEMAS Sapienza University of Rome.

- Ogbo Ann and Agu C. N (2012) "The Role of Entrepreneurial in Economic Development: The Nigerian Perspective" European Journal of Business and Management Vol. 4. No 8 pp 95-105.

- Ogboru P. L (2005) "An Evaluation of Funding Arrangements for Small and Medium Scale Enterprises in Nigeria" Unpublished PhD Thesis, St. Clements University Britain West Indies.

- Onuba J. (2010) "How SMEs can benefit from Micro Finance Polices" Micro Finance Africa. The Punch on the Web 15 July.

- Owoseni, O. O, and Akanbi P. A. (2011) "An Investigation of Personality on Entrepreneurial Success, "Journal Formal of Emerging Trends in Economics and Management Sciences (JETEMs), 2 (2): 95-103.

- Owualah B (1999) "The Role of Small Scale Entrepreneurship in Economic Development of Nigeria" Nigerian Institute of Management Journal Vol. (6) 2.

- Onwumere J. (2000) "The Nature and Relevance of SMEs in Economic Development". The Nigerian Banker-Journal of Chartered Institute of Bankers of Nigeria Vol. (25).

- Oteh Aruma (2009) "The Role of Entrepreneurship in Transforming the Nigerian Economy" Seventh Convocation Lecture, Igbinedon University, Okada, Edo State 4th December, 2009.

- Oyeku O. M, Oduyoye C, Asikhia O, Kabouoh M and Elem O. G (2014) "On Entrepreneurial Success of Small and Medium Enterprises (SME): A Conceptual and Theoretical Framework" Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development Vol 5, No 16, 2014.

- Simit Y and Watkins J. A. (2012) "A literature review of SMEs’ Risk Management Practices in South Africa" African Journal of Business Management Vol. 6 (21) PP 6324–6330.

- SMEDAN & NBS (2012) "Survey Report on Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises in Nigeria".

- Tarus, Daniel K and Nganga, Stephen Iruria (2013) "Small and Medium size Manufacturing Enterprises Growth and Work Ethics in Kenya" Developing Countries Studies Vol. 3 N o 2.

- Toluyemi S. T and Samuel R (2013) "Influence of Location on Performance of Micro Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) in Kwara State" Vol. 13, No. 2 Journal of Arid Zone Economy: A Publication of Department of Economics University of Maiduguri Nigeria.

- Toluyemi S. T. Adigbole E. A. and Kasum A. S (2015) "Constraints Growth and Sustainability of MSMEs in Nigeria: Perception of Entrepreneurs and Experts" African-Asian Journal of Rural Development Vol. 48 No. 1 pp 111-129.

- UNCTAD (2015) World Investment Report: Reforming International Investment Governance unctad.org/en/publicationsLibrary/wir2015_en.pdf.

- UNDP (2015) Table 2: "Trends Human Development Index 1990 2014" hdr.undp.org/en/composite/trends.

- Zimerer T. W. R, searborough 2006 "Essential entrapreneurshp and Small Business Management" New Delhi Prentice Hall of India.