Delayed Development of Symptomatic Nontraumatic Chronic Subdural Hematoma Following Surgical Excision and Radiotherapy for Intracranial Glioma Causing Cognitive Impairment: Review

Guru Dutta Satyarthee1, *, Luis Rafael Moscote Salazar2

1Department of Neurosurgery, Gamma Knife, AIIMS, New Delhi, India

2Neurosurgeon-Critical Care, RED LATINO Latin American Trauma & Intensive Neuro-Care Organization, Bogota, Colombia

Abstract

Neurological worsening in case of glioma during follow-up period, following gross total surgical excision and subsequently received radiotherapy, common causes are recurrence of lesion at the operative site, radiation necrosis, radiation induced intracranial tumor recurrence at distant site, seizure, vasculitis, hydrocephalus, meningitis, however, rarely chronic subdural haematoma can also be responsible. Authors report a 39-year -old female with grade II astrocytoma in the right temporal lobe, underwent craniotomy and gross total excision of glioma, received radiotherapy and a course of chemotherapy. She presented with recurrence of symptoms, 18 months after the adjuvant therapy. Cranial computed tomography revealed chronic subdural hematoma (CSDH) and underwent burr-hole craniostomy for evacuation of chronic subdural hematoma. After surgical evacuation of chronic subdural haematoma, headache along with fresh neurological deficit improved completely. To the best of knowledge of authors, current study is the first report in the western literature. Pertinent literature and management is briefly discussed. Authors recommends, possibility of chronic subdural hematoma development in the follow-up period must also be kept as one of differential diagnosis for neurological worsening of surgically resected glioma followed by radiotherapy.

Keywords

Corpus Callosal Glioma, Radiotherapy, Chronic Subdural Hematoma

Received: June 29, 2016

Accepted: July 22, 2016

Published online: August 16, 2016

@ 2016 The Authors. Published by American Institute of Science. This Open Access article is under the CC BY license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

1. Introduction

Spontaneously hemorrhage can occur in 4-6% cases associated with intracranial tumours, being common in gliomas, intracranial metastasis but infrequent in pituitary adenomas [1]. The chronic subdural hematoma is an important cause of morbidity and its commonest aetiology is craniocerebral trauma, other causes includes adverse effect of chemotherapy administration, anticoagulants medications; congenital vascular malformation i.e. AV malformation, aneurysms and extremely uncommonly following sequlae of previous craniotomy or associated with haematological malignancies like acute myeloid leukaemia. Diagnosis of CSDH requires computed tomography scan of head to evaluate total amount of hematoma, assess the mass effect produced, and suitability of surgical intervention and presence of other associated intracranial pathology. Development of CSDH following craniotomy of glioma is extremely uncommon, however can occur following aneurysm clipping in casse of subarachnoid hemorrhage caused by aneurysmal rupture. However, a patient showing significant clinical neurological deterioration in case of operated glioma surgery during follow-up period, received radiotherapy following surgery, common causes reported in the literature include recurrence of lesion, radiation induced necrosis, seizure, vasculitis, hydrocephalus, meningitis however chronic subdural haematoma is extremely uncommon cause of neurological deterioration. Cornerstone of management of CSDH is commonly burr-hole drainage or rarely craniotomy is indicated if membranes are well organized and very thick and densely adherent to overlying dura. Authors report a case of chronic subdural hematoma (CSDH) developing in a case of temporal glioma, which underwent surgical resection and also received radiotherapy, developed chronic subdural hematoma 18- months following radiotherapy.

2. Case Report

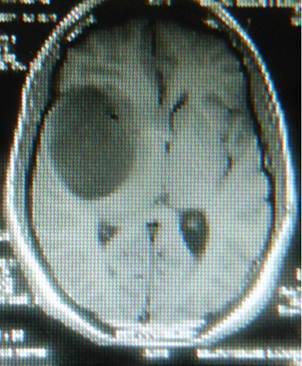

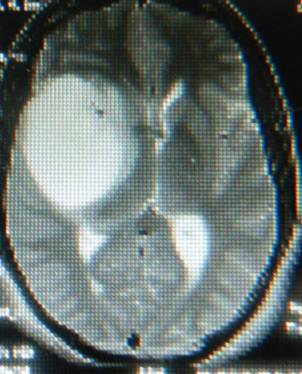

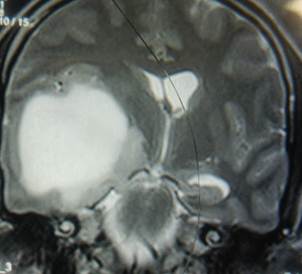

A 39- year- old house wife presented with two years history of left sided focal motor seizure with secondary generalization and associated insidious onset progressive weakness of left side of body. On examination, she was conscious, well oriented to time, place and person with no speech or memory impairment, but minimal left sided hemiparesis was present. Magnetic resonance image on T1WI, axial section showed presence of a large mass lesion, located in the right temporal region, showing hyperintense signal, (Fig-1) causing significant mass effect with lifting and upward displacement of ipsilateral right Sylvian fissure and also causing compression of ipsilateral lateral ventricle with subfalcine herniation and transtentotrial herniation, which on T2 W image showed hyperintense signal (fig-2, 3). On sagittal section image onT1W image showing anterior displacement of Sylvian cistern and contained branches of the middle cerebral arteries. (Fig: 4) A radiological diagnosis of glioma was made. She underwent gross total surgical excision under general anaesthesia (fig -5). The histopathological examination revealed astrocytoma grade II. In the immediate post-operative period, she received adjuvant therapy. A total dose of 64 Gy radiations was administered over a period of 6 -weeks. A repeat follow-up contrast CT scans of the cranium one year after radiotherapy revealed marked regressions in the size, she was doing well.

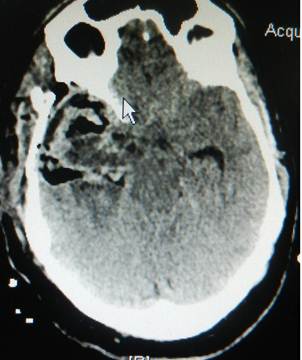

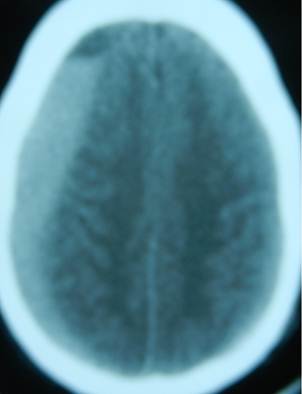

She again presented with of insidious onset progressively worsening headache for the last three months and aggravation of residual left hemiparesis for two months. A CT scan of head was performed to exclude the recurrence of lesion in view of recurrence of previous symptoms. CT scan head revealed iso-dense chronic subdural hematoma over right frontal and parietal region with effacement of sulci and compression of ipsilateral frontal horn. There was subfalcine herniation and significant midline shift (Fig-6). The routine haematological and biochemistry test, bleeding and coagulation parameters were within normal limits.

Fig. 1. Magnetic resonance imaging, T1W image, axial section showing hyperintense mass lesion, located in the right temporal lobe, causing significant mass effect, anterior displacement of adjacent frontal lobe.

Fig. 2. Magnetic resonance imaging, T2W, axial section image showing signal intensity like CSF, temporal mass lesion with subfalcine herniation.

Fig. 3. Magnetic resonance imaging, T2W image, coronal section showing hyperintense, mass lesion in the temporal lobe, causing effacement of ipsilateral lateral horn and chinked temporal horn, causing upward displacement of Sylvian fissure a with subfalcine herniation.

Fig. 4. Magnetic resonance imaging, T1W image, sagittal section showing large hyperintense mass lesion in the right temporal lobe.

Fig. 5. Post-operative non-contrast enhanced cranial computed tomography scan showing resected surgical cavity with evidence air-pockets in the cavity.

Fig. 6. Non-contrast enhanced cranial computed tomography scan showing marked right frontoparietal isodense chronic subdural haematoma producing significant mass lesion with midline shift.

She underwent right frontal burr-hole and evacuation of chronic subdural collection, which was two cm thick, consisting of dark colour fluid mixed with altered blood, came under high pressure. Brain was pulsating at the end of the surgery. Histopathology of the outer membrane taken during the hematoma evacuation revealed only inflammatory infiltrates, however, no malignant cells were observed even on cytological examination of subdural collection. Postoperatively, she had complete resolution of headache and hemiparesis. She was well at the last follow-up 6 months after the evacuation of chronic subdural hematoma.

3. Discussion

Chronic subdural haematoma in patients under 50 years of age should be considered as rare occurrence [2]. The reduced brain-duramater interface, which partially prevents brain motion under trauma and cortico-dural disruption, decreases the chances of subdural collection. The incidence of hemorrhage in brain tumours is 3.9%, but incidence will rise up to 15% if microscopic and /or sub clinical hemorrhage is also considered [3, 4]. Hemorrhage tendency vary with histology of tumours but overall as a group, metastatic tumours are relatively more likely to produce hemorrhage than primary. Although spontaneous hemorrhage has been reported virtually with almost every histological type of intracranial tumour. Among primary tumour of brain, gliomas are most prone to produce spontaneous bleed. Glioblastoma multiformre, oligodendroglioma and mixed glioma has highest rate of spontaneous bleed [4].Among the intrinsic brain tumours, intratumoral hemorrhage is by far the commonest pattern, followed by intra-parenchymal, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and subdural hematoma development. Wakai et al reported the relative incidence of these were 67%, 15.5%, 15.5% and 2% respectively [5]. In meningioma subarachnoid hemorrhage is commonest presentation than intrinsic tumours. Kohli and Crouch reported after analysis of 46 meningiomas, relative incidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage was 30.4%, intracerebral 28.3% intra and extra-parenchymal 23.9%, subdural 10.9%, intratumoral 2.2% and other 6.5% [6]

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the mechanism of haemorrhage occurring in the intracranial tumour. The vascular supply of tumour is outrunning the required supply, evident as areas of central necrosis being commonly attributed to bleed inside metastatic tumour. Even structural failure of tumor vessel is also important factor. The vascular organization of tumour is also very aberrant. The endothelial proliferation along with microvasculature of malignant gliomas dispose a network of tortuous and glomeruliod vessels with conglomerate of retiform capillaries, immature capillary buds and thin wall sinusoid [7]. Even such microvasculature are prone to progressive thrombosis leading to infarction of tumor, loss of perivascular support and increasing chances of bleed. As peritumorlal angiogenesis spread from host vessels, peritumoral normal brain also shows aberration of microvasculature promoting intracerebral bleed. Even widespread structural failure is also attributed for genesis of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Even direct spread of gliomas to surface of cerebral hemisphere and direct erosion of cerebral vessels and pseudo aneurysm may also contribute [8,9]. However, in present case, tumour was not surfacing and its size has reduced significantly following radiotherapy. However, in minority of cases a coagulation disorder may be the confounding factor.

Intracranial tumor associated with bleed may either have acute or chronic presentation. However, substantial portion of cases present with subacute progression mimicking evolving stroke [4]. In most of the cases the bleed may the first sign of underlying lesion. So imaging should be carried out, non-contrast enhanced CT scan shows better delineation of hematoma and those with contrast shows tumour [11-17]. A hemorrhage whose radiographic appearance or location deviates slightly from typical hypertensive, aneurysmal, or amyloidal angiopathy, tumour should be suspected and MRI or angiography may be required to establish the diagnosis and subsequent further management [10-12]. Where surgery is indicated, every attempt should be made for as complete resection. Residual tumour may promote recurrence or further bleed. If tumour is not visible after drainage of subdural hematoma biopsy should always be taken to exclude tumour as possible aetiology [18]. Mahayana et al reported three case of chronic subdural hematoma which was observed as metastatic deposit from acute monocytic leukaemia in one year old girl, while rest two cases were elderly patients suffering with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and gastric carcinoma with mammary carcinoma [13]. Authors further reported cytology of subdural fluid revealed presence of malignant cell in one- year- old girl and biopsy of outer membrane of CSDH revealed invasion with metastatic adenocarcinoma with overall 66% positive yield. Further authors stressed the importance of cytological and histopathological examination in every case of chronic subdural hematoma specially suspected to harbour metastatic disease must be carried out. In our case, cytology for malignant cells was negative and histopathology of outer membrane of CSDH did not show evidence of either glioblastoma or metastatic disease.

Takahashi et al analyzed development of chronic subdural hematoma (CSDH) in the post-operative period following craniotomy observed in only four cases out of 372 patients following craniotomy surgery and noted in one case with aneurysm surgery and rest with brain tumor surgery with observed overall incidence of CSDH rate is 1.1%. The chronic subdural hematoma (CSDH) in the post-operative period following craniotomy period developed after 3 to 5 months with a mean of 4.3 months. CSDH were located on the operative sides in three patients and the contralateral side in the rest one case. Although early computed tomography scans revealed presence of the subdural fluid collection in all patients and well substantiated again with Magnetic resonance imaging showing linear meningeal enhancement in all patients. CSDH development in the post-operative period may represent mixture of blood in subdural cerebrospinal fluid collection which persists due to wider opening of subarachnoid membrane resulting in to neomembrane formation and reduced brain elasticity leading to development of hematoma [19]. Satyarthee et al reported occurrence of symptomatic chronic subdural haematoma (CSDH) following transsphenoidal decompression of pituitary adenoma, managed with surgical evacuation, which was solitary case observed in a series of 480-transsphenoidal surgery series. A 52-year old female underwent transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary adenoma. She developed cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea in the immediate post-operative period, which responded to conservative therapy. She presented with severe headache and paresis of left lower limbs one month after cessation of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea, which necessitated burr hole evacuation of chronic subdural haematoma following which, noticed complete resolution of headache and limb paresis. [16]

4. Conclusion

In patients suffering from intracranial malignancy, developing recrudesce of previous symptoms after a prolonged period of relief, following surgical therapy and/or adjuvant therapy, chronic hematoma should also be kept as differentials although rare possibility but important cause, which can be readily managed with gratifying result. Special care should be given during interpretation of neuroimaging, as isodense chronic subdural hematoma may be missed on plain CT scan film. The cytological and histopathological examination also must be carried out to find out a possible aetiology. Simple surgical procedure for evacuation of chronic subdural hematoma may provide immediate relief of symptoms, however, few cases may respond even to conservative therapy and extremely uncommonly may need craniotomy.

References

- Scott M. Spontaneous intracerebral hematomas caused by cerebral neoplasms. J Neurosurg. 1975; 42:338-342.

- Missori P, Maraglino C, Tarantino R, Salvati M, Calderaro G, Santoro A, Delfini R. Chronic subdural haematomas in patients under 50. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 2000; 102:199-202.

- Salcman M. Intracranial hemorrhage caused by brain tumour. In: Kangman HH. (Ed) Intracerebral hematomas, New York, Raven Press. 1992, pp95-106.

- Kondziolka D, Bernstein M, Resch L et al. Significance of hemorrhage into brain tumours: Clinicopathological study. J Neurosurg. 1987; 67; 852-857.

- Wakai S, Yamakowa K, Monaka et al. Spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage caused by brain tumours, its incidence and clinical significance. Neurosurgery 1982; 10; 437-444.

- Kohli CM, Crouch RL. Meningioma with intracerebral hematoma. Neurosurgery. 1984; 15:237-240.

- Liwnicz BH, Wusz, Tew JM. The relationship between the capillary structure and haemorrhage in gliomas. J Neurosurg. 1987; 66:536-541.

- Glands B, Abott KH. Subarachnoid hemorrhage consequent to intracranial tumour. Review of the literature and report of seven cases. Am Med Assoc Arch Neurol Pshychia. 1955; 73:369-379.

- Cowel Rl, Siqudra EB, George E, Angiographic demonstration of glioma involving the wall of anterior cerebral artery. Report of a case Radiol 1970; 97:577-578.

- Prabhu VC, Bailes JE. Chronic subdural hematoma complicating arachnoid cyst secondary to soccer –related head injury: Case report. Neurosurgery. 2002; 50:195-198.

- Ranganadham P, Mohandas S, Purohit AK, Ratnakr KS, Dinkar I. Subdural haematoma associated with fibroblastic meningioma: Case report and review of literature Neurol India. 2001; 49:182-184.

- Tsai FG, Huprich JE, Segall HD, Teal SJ. The contrast-enhanced CT scan in the diagnosis of isodense subdural hematoma. J Neurosurg. 1979; 50:64-69.

- Mashiyama S, Fukawa O, Metani S, Asano S, Sai T. Chronic subdural hematoma associated with malignancy: report of three cases. No Shinkei Geka. 2000; 28:73-178.

- Satyarthee GD, Mahapatra AK. Giant pediatric glioblastoma multiforme causing primary calvarial erosion and sutural diastasis presenting with enlarge head in 13-year old boy: Rare entity. J Ped Neurosciences. 2015; 10:290-293.

- Raheja A, Satyarthee GD, Mahapatra AKChronic subdural hematoma development in accelerated phase of chronic myeloid leukemia presenting with seizure and rapid progression course with fatal outcome. Romanían Neurosurgery. 2015; 29(2):199-202.

- Satyarthee GD. Chronic Subdural haematoma development following transsphenoidal surgery for Pituitary Adenoma Apoplexy: An incidental or Real Association. American Journal Clinic Neurol Neurosurg. 2015; 1 (3):150-153.

- Borker SA, Satyarthee GD, Mahapatra AK, "Armoured brain"syndrome: chronic calcified subdural hematoma. Pan Arab J Neurosurg 2013:17; 23-27.

- Garg K, Singh PK, Chandra PS, Singh MM, Satyarthee GD, Sharma BS. Bilateral armoured syndrome due to calcified subdural hematoma following VP shunt surgery. Neurol India. 2013; 63:548-550.

- Takahashi Y, Ohkura A, Sugita Y, Sugita S, Miyagi J, Shigemori M. Postoperative chronic subdural hematoma following craniotomy--four case reports. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1995;35(2):78-81.