Impacts of Tourism Development in Cultural and Heritage Sites: An Empirical Investigation

W. K. Athula Gnanapala, J. A. R. C. Sandaruwani*

Dept. of Tourism Management, Faculty of Management Studies, Sabaragamuwa University of Sri Lanka, Belihuloya, Sri Lanka

Abstract

Tourism has become an important industry in the Sri Lankan economy and placed the fourth largest source of foreign exchange earner of the national economy in 2015. As a developing country, Sri Lanka takes much effort to develop tourism as an economic development strategy and it is targeted to attract 2.5 million of tourists by 2016. In this scenario, the cultural and heritage attractions are considered as an important area for future tourism developments. Sri Lanka is rich with 6 cultural world heritage sites, declared by UNESCO, and other important cultural treasures and attractions. Therefore, the main objective of this paper is to discuss the impacts of tourism development in cultural and heritage sites in Sri Lanka and their implications for heritage management and sustainability of the industry. The study is carried out in the cultural world heritage sites in Sri Lanka and has adopted a range of data collection methods including semi-structured interviews, focused group discussions, document analysis, and participant observation and also gathered secondary data from online media. The findings revealed that even though tourism has brought many economic and socio-cultural advantages, there are several issues and problems that need to be addressed comprehensively such as over concentration on tourism, the conflicts of interests, unauthorized constructions and modifications, misinterpretations through guiding and poor site management etc. These factors have created dissatisfaction among the tourists and finally the negative publicity about the destination. It has concluded that the relevant and responsible authorities have to take necessary actions to answer the said problems and issues before further degradation of tourism occurs in heritage and cultural sites; otherwise the country has to endure further negative consequences.

Keywords

Cultural Tourism, Impacts, Industry Sustainability, Tourism Development, World Heritage Sites

Received: June 16, 2016

Accepted: August 19, 2016

Published online: November 12, 2016

@ 2016 The Authors. Published by American Institute of Science. This Open Access article is under the CC BY license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

1. Introduction

Tourism has become an important industry in the Sri Lankan economy and was the fourth largest source of foreign exchange earnings for the national economy in 2013. As a developing country, Sri Lanka takes much effort to develop tourism as an economic development strategy and is targeted to attract 2.5 million of tourists by 2016. In this scenario, the cultural and heritage attractions are considered as an important area for future tourism developments. Sri Lanka is rich with 6 cultural world heritage sites, declared by UNESCO, and other important cultural treasures and attractions.

There are many definitions on cultural tourism, for example, [54] defines it as the movement of persons to cultural attractions in cities in countries other than their normal place of residence, with the intention to gather new information and experiences to satisfy their cultural needs and all movements of persons to specific cultural attractions, such as heritage sites, artistic and cultural manifestations, arts and drama to cities outside their normal country of residence.

According to [55], tourism has experienced continued growth and deepening diversification to become one of the fastest growing economic sectors in the world. Modern tourism is closely linked to development and encompasses a growing number of new destinations. These dynamics have turned tourism into a key driver for socio-economic progress. As highlighted by [16] the cultural dimensions are powerful pull motives to attract the tourists to a destination.

Cultural and heritage tourism, as a form of alternative tourism is one of the most significant and fastest-growing global tourism segments [1], [19] because of the tourists’ inclination to seek out novelty, including that of traditional cultures, history, lifestyles of a particular destination [10], [58] & [16]. Furthermore, past studies suggest that the purpose of visiting cultural and heritage sites is to enhance learning, grow spirituality, satisfy curiosity, relax and get away from daily routines [51], [37], & [17].

An integration of physical, psychological and social elements of cultural landscapes with inherent cultural heritage values is the main motivation factors of the tourists. Culture, heritage and creative industries are increasingly being used to promote destinations and enhance their competitiveness and attractiveness. Many locations are now actively developing their tangible and intangible cultural and heritage assets as a means of developing comparative advantages in an increasingly competitive tourism marketplace, and to create local distinctiveness in the face of globalization. However, those precious elements and values seem to become degraded whereas they actually shape the heritage tourism destination and when incorporated with an integration of the traditional community and its landscapes, they offers tourists a destination with cultural heritage tourism [46].

Recent studies have been focused on cultural and heritage tourism in identifying the characteristics, development, and management of cultural and heritage tourism, as well as on investigating demographic and travel behavior characteristics of tourists who visit cultural and heritage destinations. But, there have been few studies that identify the effect of tourism development in cultural and heritage sites. According to [38] cultural and heritage tourism strategies in various countries have in common that they are a major growth area, that they can be used to boost local culture, and that they can aid the seasonal and geographic spread of tourism. Based on this background, the main objective of this paper is to discuss the impacts of tourism development in cultural and heritage sites in Sri Lanka and their implications for heritage management and sustainability of the industry.

2. Literature Review

The literature review first discusses the definitions of cultural and heritage tourism, as well as explains the benefits of cultural/heritage tourism. Next, it discusses the cultural and heritage sites in Sri Lanka and finally it describes the impacts of tourism developments in cultural and heritage sites.

2.1. Cultural and Heritage Tourism

There is no explicit definition of either cultural or heritage tourism. According to [11], some call it as cultural tourism, some as heritage tourism, and some as cultural & heritage tourism or shortly cultural heritage tourism. However, there are many definitions given by different scholars or institutes for cultural and heritage tourism, also known simply as cultural tourism or heritage tourism.

As highlighted by [9], "culture and heritage tourism occurs when participation in a cultural or heritage activity is a significant factor for traveling. Cultural tourism includes performing arts (theater, dance, and music), visual arts and crafts, festivals, museums and cultural centers, and historic sites and interpretive centers".

According to [59], "the movement of persons to cultural attractions in cities in countries other than their normal place of residence, with the intention to gather new information and experiences to satisfy their cultural needs and all movements of persons to specific cultural attractions, such as heritage sites, artistic and cultural manifestations, arts and drama to cities outside their normal country of residence"

Further, US National Endowment for the Arts highlights cultural tourism as the "travel directed toward experiencing the arts, heritage, and special character of a place. America’s rich heritage and culture, rooted in our history, our creativity and our diverse population, provides visitors to our communities with a wide variety of cultural opportunities, including museums, historic sites, dance, music, theatre, book and other festivals, historic buildings, arts and crafts fairs, neighborhoods, and landscapes".

According [21], cultural and heritage tourism encompasses landscapes, historic places, sites and built environments, as well as biodiversity, collections, the past and continuing cultural practices, knowledge and living experiences. Furthermore, it records and expresses the long processes of historic development, forming the essence of diverse national, regional, indigenous and local identities and is an integral part of modern life. Together, all these definitions emphasize the various dimensions of this sector.

2.2. Cultural and Heritage Tourism in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka has a massive potential to offer value-added products that could meet the expectations of high-end tourist markets with the rich natural reserves and abundant cultural heritages. Because the cultural and heritage sites have diverse and unique characteristics which make them stand out among other tourist attractions. According to [24], heritage site is a place which is historically evolved, unique and extremely rare and its authenticity is its main attractiveness for tourists to visit. Sri Lanka's cultural and heritage attractions are spread all around the island. However, the major concentration of cultural attractions of Sri Lanka lies within a zone called "Sri Lanka Cultural Triangle" in the central and north-central provinces (Figure 1); which is the area of concentration for this paper. The origin of the concept of Sri Lanka Cultural Triangle lies in the UNESCO-sponsored project launched to preserve the major cultural, historical, archaeological and Buddhist sites of Sri Lanka located within the North Central region called WeweBandi Rata (English: the land of man-made irrigation reservoirs) and also called Raja Rata (English: the king's domain) during ancient times. Figure 1 gives a clear understanding about the areas covers under this study.

By sheer coincidence, the locations of Sri Lanka's prime cultural attractions can be contained within an imaginary triangle (approximately each side is 80 km) connecting the three cities of Anuradhapura to the north; Polonnaruwa to the east; and Kandy to the south, all of which are incidentally UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Then again, as if those three glorious cities wouldn't do, the cultural attractions of Sigiriya Lion Rock Citadel and Golden Dambulla Rock Cave Temple more or less in the very centre of the Sri Lanka Holidays Cultural Triangle are by no means, mere tourist attractions: those two are UNESCO World Heritage Sites too [39].

The other remaining cultural world heritage site; located beyond the cultural triangle is the Old Town and the Fortress of Galle.

Figure 1. Location of World Heritage Sites within Sri Lanka.

Source: Wikipedia, 2015

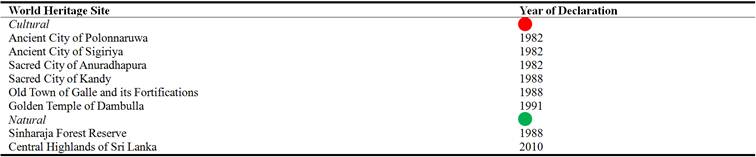

Table 1. UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Sri Lanka.

Source: UNESCO, 2015

However, the island also faces many challenges to utilize those resources for tourism, which mean good and effective strategies are required to strengthen heritage tourism. Introducing policies and principles that are aimed at promoting tourism in heritage sites and ecological areas, development of infrastructure, educating the local communities, tourism strategies to attract heritage and eco-tourists who prefer specialized services are some of the challenges [50].

2.3. Impacts of Tourism Development

Government bodies focus on tourism developing in with the aim of maximizing selected positive impacts while minimizing potential negative impacts. First, it is essential to identify the possible impacts. Various tourism researchers have identified a large number of impacts in the areas of economic impacts, socio-cultural impacts and environmental impacts [3], [4], [5], [13], [18], [22], [23], [27], [28], [33], [36], [43] & [56].

Tourism impact can be classified as negative when they lead to the disruption of society’s components, and as positive when they upgrade vital attributes. Tourism and its influence on host communities have given highly controversial beliefs: some suggest that it is an opportunity for underdeveloped countries to provide economic growth and social wellbeing development. Oppositely, some researchers pointed out that mass tourism may obstruct the authenticity of local cultures [35]. But, the majority of studies have shown that residents, who perceive a greater level of economic gain or personal benefit, tend to have more positive perceptions of impact than others [5], [18], [23], [27], [48] & [32].

2.3.1. Positive Economic Impacts

Tourism developments highly contribute to the income generation, improvement of economic quality of life through increasing of personal income and increasing tax revenues [30], [34] & [26] increases employment opportunities, improves investment development, and profitable local businesses [22], [29], and investment in infrastructure, improves public utilities infrastructure, improves transport infrastructure [22], [18], [25], [45] & [47], increases opportunities for shopping, economic impact (direct, indirect, induced spending) is widespread in the community and creates new business opportunities.

2.3.2. Negative Economic Impacts

The negative economic impacts of tourism development are increasing price of goods and services, increasing price of land and housing, increasing cost of living, increasing potential for imported labour, cost for additional infrastructure (water, sewer, power, fuel, medical, etc.), increasing road maintenance and transportation systems costs, creating seasonal tourism high-risk under- or unemployment issues, severe competition for land with other (higher value) economic uses, profits may be exported by non-local owners, jobs may pay low wages [26], [18] & [29].

2.3.3. Positive Socio Cultural Impacts

According to [41], indicated the potential positive socio-cultural impacts including; building community pride, enhancing the sense of identity of a community or region, promoting intercultural/international understanding, encouraging revival or maintenance of traditional crafts, enhancing external support for minority groups and preservation of their culture, broadening community horizons, providing funding for site preservation and management; and enhancing local and external appreciation and support for cultural heritage.

The social and cultural ramifications of tourism warrant careful consideration, as impacts can either become assets or detriments to communities. Tourism development can positively affect in improving quality of life [26] facilitates meeting visitors (educational experience) positive changes in values and customs, promotes cultural exchange, improves understanding of different communities [12] & [47] preserves cultural identity of host population [48] increases demand for historical and cultural exhibits, cultural events, entertainment facilities, historical and cultural exhibits, and cultural exchange [29] greater tolerance of social differences [6], satisfaction of psychological needs.

Cultural and heritage tourism offers several benefits to tourists and residents, as well as governments. First of all, cultural and heritage tourism protects historic, cultural, and natural resources in communities, towns, and cities. People become involved in their community when they can relate to their personal, family, community, regional, or national heritage. This connection motivates residents to safeguard their shared resources and practice good stewardship. Second, cultural and heritage tourism educates residents and tourists about local/regional history and traditions. Through the research about and development of heritage/cultural destinations, residents will become better informed about local/regional history and traditions which can be shared with tourists. Third, cultural/heritage tourism builds closer, stronger communities. Knowledge of heritage provides continuity and context for communities, which instils respect in their residents, strengthens citizenship values, builds community pride, and improves the quality of life. Fourth, cultural/heritage tourism promotes the economic and civic vitality of a community or region. Economic benefits include: the creation of new jobs in the travel industry, at cultural attractions, and in travel-related establishments; economic diversification in the service industry (restaurants, hotels/motel, bed-and-breakfasts, tour guide services), manufacturing (arts and crafts, souvenirs, publications), and agriculture (specialty gardens or farmers’ markets); encouragement of local ownership of small businesses; higher property values; increased retail sales; and substantial tax revenues [57].

2.3.4. Negative Socio Cultural Impacts

According to [41], the potential negative socio-cultural impacts are such as commoditization and cheapening of culture and traditions, alienation and loss of cultural identity, undermining of local traditions and ways of life, displacement of traditional residents, increased division between those who do and do not benefit from tourism, conflict over (and at times loss of) land rights and access to resources (including the attractions themselves), damage to attractions and facilities, loss of authenticity and historical accuracy in interpretation; and selectivity in which heritage attractions are developed.

Tourism can bring to a community with a dark social and cultural side and create various negative impacts to the host culture, too. Illegal activities tend to increase in the relaxed atmosphere of tourist areas. Increased alcohol use and underage drinking can become a problem especially in beach communities, areas with festivals involving alcohol, and ski villages [18], [31], [52] & [26]. It is easier to be anonymous where strangers are taken for granted; bustling tourist traffic can increase the presence of smugglers and buyers of smuggled products and as well as tourism is a potential determinant of crime [5], [18], [31] & [52]. Lifestyle changes such as alterations in local travel patterns to avoid tourist congestion and the avoidance of downtown shopping can damage a community socially and culturally. Hotels, restaurants and shops can push tourism development into residential areas, forcing changes in the physical structure of a community. Development of tourist facilities in prime locations may cause locals to be or feel excluded from those resources and fell loss of resident identity and local cultures such as habits, daily routines, social lives, beliefs, and values [14] & [42]. The "demonstration effect" of tourists (residents adopting tourist behaviors) and the addition of tourist facilities may alter customs, such as dating habits, especially those of a more structured or traditional culture. The potential of meeting and marrying non-local mates may create family stress [26].

Furthermore, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) highlighted the prostitution and sex tourism severe as negative socio-cultural impacts of tourism development. Further, it describes the commercial sexual exploitation of children and young women have paralleled the growth of tourism in many parts of the world. Though tourism is not the cause of sexual exploitation, it provides easy access to abuse and exploitation. Tourism also brings consumerism to many parts of the world previously denied access to luxury commodities and services. The lure of this easy money has caused many young people, including children, to trade their bodies in exchange for T-shirts, personal stereos, bikes and even air tickets out of the country. In other situations children are trafficked into the brothels on the margins of the tourist areas and sold into sex slavery, very rarely earning enough money to escape.

2.3.5. Positive Environmental Impacts

According to [26], tourism development helps for the protection of selected natural environments or prevention of further ecological decline, preservation of historic buildings and monuments, improvement of the area’s appearance (visual and aesthetic), a "clean" industry (no smokestacks).

Tourism can directly contribute to the conservation and preservation of sensitive areas and habitats through the revenue earned from entrance fees and similar sources [7]. Some governments collect money in more far-reaching and indirect ways that are not linked to specific parks or conservation areas. User fees, income taxes, taxes on sales or rental of recreation equipment, and license fees for activities such as hunting and fishing can provide governments with the funds needed to manage natural resources. Such funds can be used for overall conservation programs and activities, such as park ranger salaries and park maintenance [7].

[49] elaborates how tourism can contribute to environmental conservation; first, Improved Environmental Management and Planning; planning early for tourism development, damaging and expensive mistakes can be prevented, avoiding the gradual deterioration of environmental assets significant to tourism. Second, raising Environmental Awareness; tourism has the potential to increase public appreciation of the environment and to spread awareness of environmental problems when it brings people into closer contact with nature and the environment. Third, Regulatory Measures; regulatory measures help offset negative impacts; for instance, controls on the number of tourist activities and movement of visitors within protected areas can limit impacts on the ecosystem and help maintain the integrity and vitality of the site. Such limits can also reduce the negative impacts on resources.

2.3.6. Negative Environmental Impacts

Tourism development has potential negative impacts on the environment as it creates air, water, noise, solid waste, and visual pollution [5], [15], [28] & [8] loss of natural landscapes and agricultural lands to tourism development, loss of open space, destruction of flora and fauna (including collection of plants, animals, rocks, coral, or artifacts by or for tourists), degradation of landscape, historic sites, and monuments, water shortages, introduction of exotic species, disruption of wildlife breeding cycles and behaviors [26], [2] & [7]. Influx of tourists creates traffic and noise [2], [5], [22], [25], [30] & [34] which leads to the congestion and overcrowding [6] & [7].

3. Methodology

The study is carried out in the cultural world heritage sites in Sri Lanka and has adopted a range of data collection methods including semi-structured interviews, focused group discussions, document analysis, and participant observation and also gathered secondary data from online media. The use of different data collection methods allowed for triangulation that enabled the researchers to examine where the data converged and, in turn, provide credibility for the findings (Bowen, 2009; Denzin, 2006). The secondary data used for this research was based on government policy documents, annual statistical reports prepared by Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority, peer-reviewed academic journals and books, official websites.

The study is carried out covering all the six cultural world heritage sites in Sri Lanka such as Sacred City of Anuradhapura (1982), Ancient City of Polonnaruwa (1982), Golden Temple of Dambulla (1991), Ancient City of Sigiriya (1982), Sacred City of Kandy (1988) and the Old Town of Galle and its Fortifications (1988). The data collected from the tourists, officers of the respective sites, tour guides and vendors adopting a range of qualitative methods including semi-structured interviews, focused group discussions, document analysis, and participant observation and also gathered secondary data from online media.

The interviews were guided by a set of pre-determined questions about the cultural tourism and its impacts; both negative and positive on cultural and heritage sites in Sri Lankan. The purpose of the interviews was to identify the benefits of tourism development in cultural and heritage sites and to identify the stakeholder attitudes on the impacts.

The active participant observation was used to collect primary data to enable an increased understanding of the behavior of the foreign tourists, officers, tour guides, vendors, pilgrimages (domestic tourists) and others. Also, highlighted by Podoshen (2013) participant observation assist the researchers in determining the accuracy of the information gathered though other primary and secondary data sources. The primary data collected during the month of July and August 2015 employing the undergraduates who follow their degrees in Tourism Management. The active participant observations were conducted by the researchers by themselves using a predetermined checklist to maintain the accuracy of the information. Interview participants were selected via a non-random, convenience and snowball sampling method (Kitchenham & Pfleeger, 2002; Coyne, 1997; Patton, 1990). Finally, the content analysis and the narrative analysis were employed to analyze the collected data to meet the objectives of the study.

4. Findings

The findings concluded that the cultural tourism has brought many economic and socio-cultural advantages. With a history expanding over 3000 years, Sri Lanka holds world heritage sites including their once glorious townships, palaces, temples, monasteries, hospitals, museums and theaters etc. The cultural and heritage sites have become one of the key pull motives of the country to stimulate the tourists’ interest to visit Sri Lanka. As a result, the travel agent and tour operators include those places to the travel itineraries of the foreign tourists.

4.1. Positive Impacts

4.1.1. Income Generation

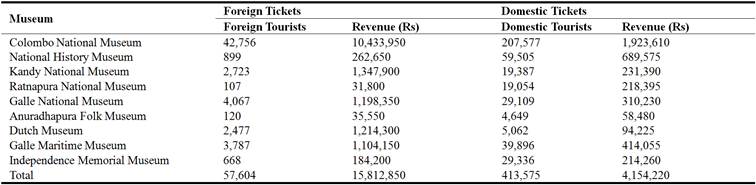

The tourists visit many different places related to the culture and heritage of the country. The museums are becoming more attractive to the foreign tourists and 57,604 tourists have visited museums and the country has earned Rs. 15,812,850 in 2014. Table 2 has summarized the tourists both foreign and locals who visited the national museums and the income earned from them in 2014.

Table 2. Number of Visitors in Museums and Revenue – 2014.

Source: SLTDA, 2015

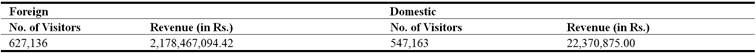

The archeological and historical monuments play a major role to attract a large number of tourists to the world heritage sites and other historical sites. The tourists generate a considerable income to the government revenue. The table 3 and table 4 have summarized the income received through tourism.

Table 3. Number of Visitors Visiting the Cultural Triangle and Income from Sale of Tickets – 2014.

Source: SLTDA, 2015

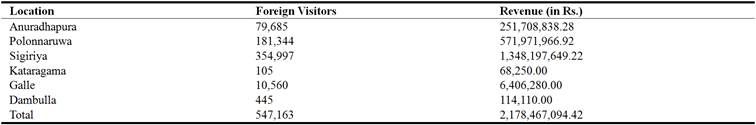

Table 4. Foreign Tourists Visiting the Cultural Triangle and Income (Details by Locations) – 2014.

Source: SLTDA, 2015

In 2014, a large number of foreign tourists, 627,136, have visited the cultural triangle and therefore has earned Rs. 2,178,467,094.42 and the majority have visited Sigiriya (354,997 foreign tourists) and Polonnaruwa (181,344 foreign tourists) respectively when comparing with other archaeological places. These figures are clearly mentioned in table 3. According to SLTDA (2014), Sigiriya has become the highest foreign income earning cultural site in Sri Lanka and has earned Rs. 1,348,197,649.22 in 2014.

Sri Lanka as a developing country otherwise faces much difficulties in allocating money to maintain, restoration and development activities in archaeological and historical places. Therefore, the earned money can be used for conservation, restoration of the sites and also for the provision of more improved facilities for the tourists; both international and domestics. However, when we consider the present situation of the study sites, the collected money is not fully utilised for the restoration and development of the sites instead of that the money goes to the treasury and need to receive money back from treasury (Personnel communication with government officers). It is revealed that the government and other related authorities are highly interested to develop tourism in culturally important places without assessing the feasibility and the possible negative impacts of tourism development in cultural sites.

4.1.2. Employment Generation

As usual, the cultural and heritage sites have generated more employment opportunities both direct and indirect for the poor rural community live surrounding areas. Most of the cultural attractions are situated in very remote areas in the dry zone, therefore the majority of the community depend on agriculture and it is seasonal and it is affected severely by the bad weather conditions i.e. drought and flood, therefore the community has faced a lot of difficulties to fulfill their basic needs. However, the community is able to work in tourism and supportive organizations. In addition to that, the people work as helpers and site guides as well as doing self-employments targeting the tourists. For example, the community has started small scales shops to provide foods, beverages, fruits, vegetables, souvenir items etc. Also, provide accommodation facilities for both domestic and international tourists as home-stays units.

4.1.3. Development of Cottage and Supportive Industries

Cottage industry brings products and services which are often unique, distinctive, and home-based; usually not mass-produced and typically people engage in their part time. It is obvious to see, the development of tourism industry in the cultural and heritage sites has given the rebirth to the cottage industry and other supportive industries such as pottery, woodcarvings, brassware and silverware, lacquer work, handlooms, batik, reed and rush ware, wooden masks, lace making etc.

As the majority of the local communities surrounded by the cultural and heritage sites are engaged in agriculture, they have both the time and the desire to have additional income throughout the year as the agriculture is seasonal and severely affected by the bad weather conditions. So the majority is trying to engage in home-based tourist product manufacturing and service delivering to the tourists as it is much easier and profitable than the exhausting agriculture. Also, nowadays most of the tourists prefer to purchase such unique home-made products as souvenirs.

4.1.4. Supports for Regional Development

The rural areas get benefits through tourism development. The infrastructure facilities have developed rapidly in rural areas for examples the road networks, water, electricity and safety and security etc.

4.2. Negative Impacts

Even though the tourism has brought many economic and socio-cultural advantages, there are some problems and issues related to the tourism development in cultural and heritage sites such as over-dependence on tourism, the conflicts of interests, unauthorized constructions and modifications, misinterpretations through guiding and poor site management etc. These issues have created dissatisfaction among the tourists and finally the negative publicity about the destination.

4.2.1. Overconcentration on Tourism

The cultural and archeological institutions are very much keen to attract more tourists to the respective sites in order to earn more money without considering the carrying capacity and other socio-cultural and environmental impacts. It is identified that officers of the respective sites need more tourists however there are no proper plans to provide required facilities and to manage the possible negative impacts. The main objective of the archeological and historical places is to preserve, conserve and protect these treasures to see the next generations and to tell the world about our history and heritage. The tourism development should be a secondary objective without compromising the primary objective of the cultural and heritage sites of the country.

4.2.2. Conflicts of Interests

Both domestics and international tourists visit the cultural and heritage places. The locals visit these places in relation to their religious activities, however, the foreign tourists patronage these places as a part of their round tour to get experience and satisfaction. The tourism activities may disturb the religious activities of those devotees and other pilgrimage tourists. On the other hand, the foreign tourists need to pay money to enter for those places but the locals will not pay money to enter the most of such places. Since the foreign tourists are charged, they need to get the value for their money; therefore the overcrowding and the unethical behaviors of some of the locals may negatively affect the ultimate satisfaction of the foreign tourists. It is noticed that the authorities are also more interesting about the foreign tourists than the locals since the foreign tourists bring more revenue to those places.

4.2.3. The Unauthorized Constructions and Modifications

The tourism has become a popular economic activity in all of the cultural and heritage sites of the country and also has created more business opportunities. Therefore, the various business establishments are operating with targeting the tourists in and around of those sites such as souvenir shops, hotels, restaurants and spa etc. For example, in Galle, the heritage buildings are modified, renovated and reconstructed to start those business establishments without getting the approval of the World Heritage center and without preserving the historical values. The similar things are happening in Kandy world heritage city since the tourism has become the key business and therefore the tourists require more facilities and attractive business environment. As a result, the business organizations tend to do alterations for their buildings without proper approvals. The Golden Temple of Dambulla is declared as a world heritage sites in 1991 by the UNESCO, however the recent construction of the site’s loss historical value and authenticity, a Chinese Buddha statue placed at the entrance to the temple altering its original look. In addition to that, there are many modifications and constructions have been done without getting the proper approvals and affected for the historical values. These inappropriate contractions and modifications will deteriorate the historical and aesthetic values of the destination and create the frustration and dissatisfaction among the tourists finally which lead to create negative publicity about the destination.

4.2.4. Inappropriate Behavior of Tourists

The behaviors of tourists at cultural sites really offend the feelings of people of host religions and it is considered as unethical and is obviously a punishable offense. Such unethical dilemmas of religious tourism have been recorded as kissing the Buddha statues, imitating the posture of the Lord Buddha, taking the unethical selfies with the Buddha Statues.

The unethical behavior of tourists at the cultural and heritage sites is not conforming to the operating rules, practices and advices, for example inappropriate attire of the tourists. Some tourists enter the temples with bare shoulders and knees. Furthermore, they visit the places of worship, taking simultaneously plenty of photos during the religious ceremonies and rituals. They often use mobile phones inside the premises and even during the religious services, or they talk loudly, taking the heritage away in the form of unethical souvenirs (fragments of walls, objects from the sites visited. Moreover, some sites are not properly monitored and some local guides are not restricting such unethical behaviors as they perceive it may damage the tour experience of the tourists. So, the site management officials should advertise the cues avoiding those unethical behaviors of the tourists. The local guides’ responsibility is to make the tourists aware of those site operating rules, warnings and explain their purposes prior to their arrival or entering to the site in a way that does not distract the tourists’ satisfaction.

4.2.5. Misinterpretations Through Guiding

Cases have been recorded that the local guides interpret the invaluable and rich local history of the sites in a wrong manner due to their poor knowledge about the history of the heritage sites when tourists are questioning more into the deep. This definitely damages the proud of the Sri Lankan culture and heritage. The most of the tourists read the facts related to the destinations in which they are going to have their holidays. Therefore, they come with a sound knowledge about the destination and even traveling within the destination the tourists use guides books further, due to the advanced communication technology, the majority of the tourists use portable electronic devices which help them to access to the relevant web pages to get information. It is noticed that the majority of the site guides provide contradictory information about the cultural site. Further identified that the poor proficiency of English and other foreign languages with poor communication skills has lead the tourists towards dissatisfaction and frustration at cultural and heritage sites in the country. The previous researchers also have highlighted the magnitude of this issue and its effect on the future well-being of the industry (Sandaruwani & Gnanapala, 2016).

4.2.6. Poor Site Management & Site Facility Management

Currently, the major problems of many cultural & heritage sites are high tourist traffic and the expectations of visitors. The site managers must recognize that the sites entrusted to their care will remain the same size; means that the number of visitors and their behavior has to be controlled to protect the sites. But in Sri Lanka, the priorities are reversed: tourism is being promoted before conservation.

Even though the site operators usually see their primary role as bringing more international tourists to the sites, they do not much concern about the requirement of the site facility management. Actually, as a country, we lose the economic potential of those sites if we fail in proper facility management at those cultural & heritage sites. Moreover, as the tourists are often obliged to purchase an expensive admission ticket with compared to the locals, there should be basic tourist facilities (availability of drinking water, toilets and washrooms, resting areas, professional guiding and interpretations, information centers, safety and security services) in order to satisfy them. So, improving on-site facilities and staff assistance will ensure that tourists experience value for their money.

It is noticed that there is no proper mechanism to control the behavior of tour guide, helpers and sellers (touts) who do their activities on those sites. There are some trained guides but the majority is untrained, however the Central Cultural Fund (CCF) or the Department of Archeology cannot control the behavior of tour guide and it is the responsibility of the Sri Lanka Tourism development Authority (SLTDA) and the SLTDA also cannot stop the guiding practice of the unlicensed guides due to the political and other influences.

5. Conclusion

As a developing country, Sri Lanka faces a lot of economic illness and the country has put forward tourism as one of the key development strategies. Therefore, Sri Lanka takes much effort to promote tourism as an economic development strategy and targeted to attract 2.5 million of tourists by 2016 in order to extract more economic benefits. Hence, cultural and heritage sites in Sri Lanka has become one of the major tourists attractions and they have influenced tourists to select the country as their travel destination. Sri Lanka consists of diverse cultural and heritage attractions including 6 cultural based world heritage sites and other important cultural treasures and attractions. Therefore, the main intention of this paper was to discuss the impacts of tourism development in cultural and heritage sites in Sri Lanka and their implications for heritage management and sustainability of the industry. The study has identified that cultural and heritages sites contribute to generate more economic benefits however there are many issues and problems that need to be addressed effectively as far as the sustainability of the industry is concerned. The burning issues at the cultural and heritage sites are the overconcentration on tourism, conflicts of interests, unauthorized construction and modifications, inappropriate behavior of tourists, misinterpretations and poor sit management etc.

These issues have created dissatisfaction among the tourists and finally the negative publicity about the destination. The majority of the tourists visit these places as a part of their round tour and the tourists' main travel purpose is pleasure or rest and relaxation. Therefore, the tourists expect everything to support for their satisfaction even they visit cultural and heritage sites in the country. It is concluded that the relevant authorities have to take necessary actions to answer the said problems and issues effectively before further tourism development in those heritage and cultural sites; otherwise the country has to undergo more negative consequences rather than achieving the expected economic benefits.

References

- Alzue, A., O’Leary, J. & Morrison, A. M. (1998). Cultural and heritage tourism: identifying niches for international travelers. The Journal of Travel and Tourism Studies, 9 (2), 2–13.

- Andereck, K. L. (1995). Environmental Consequences of Tourism: A Review of Recent Research. InMcCool, S. F. and Watson, A. E (eds) Linking Tourism, The Environment and Sustainability, General Technical Report No. INT-GTR-323, Intermountain Research Station, Ogton, Utah, 77-81.

- Andereck, K. L., Valentine, K. M., Knopf, R. C. & Vogt, C. A. (2005). Residents' perceptions of community tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 32 (4), 1056-1076.

- Ap, J. & Crompton, J. (1993). Residents’ strategies for responding to tourism impacts. Journal of Travel Research, 32 (1), 47-50.

- Brunt, P. & Courtney, P. (1999). Host perceptions of socio-cultural impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 26 (3), 493-515.

- Burns, P. & Holden, A. (1995). Tourism: A New Perspective. London: Prentice Hall.

- Buultjens, J., Ratnayake, I., Gnanapala, A., and Aslam, M. (2005). Tourism and its Implications for Management in Ruhuna National Park (Yala), Sri Lanka. Tourism Management, 26 (5), 733-742.

- Buultjens, J., Ratnayake, I. & Gnanapala, A. (2016). Whale Watching in Sri Lanka: Perception of Sustainability. Tourism Management Perspective, 18, 125 - 133.

- Canadian Tourism Commission. (1999). Packaging the Potential: A Five-Year Business Strategy for Cultural and Heritage Tourism in Canada. Ottawa: CTC.

- Craik, J. (1997). The culture of tourism. In C. Rojek, & J. Urry (Eds.). Touring cultures: Transformations of travel and theory (pp. 113–136). London: Routledge.

- Cultural & Heritage Tourism Alliance (2002), "CTHA: About the CTHA", http://chtalliance.com/ about.html, Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- De Kadt, E. (Ed.). (1979). Tourism: passport to development? New York: Oxford University Press.

- Demirkaya, H. & Çetin, T. (2010). Residents’ perceptions on the social and cultural impact of tourism in Alanya (Antalya-Turkey). EKEV Akademi Dergisi, 14 (42), 383-392.

- Dogan, H. S. (1989). Socio-cultural Impacts of Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 16, 216-236.

- Gilbert, D. & Clark, M. (1997). An explanatory examination of urban tourism impact, with reference to residents attitudes in the cities of Canterbury and Guildford Cities, 14 (6), 343–352.

- Gnanapala, W. K. A. C. (2012). Travel Motivations and Destination Selection: A Critique. International Journal of Research in Computer Application & Management, 2 (1), 49-53.

- Gnanapala, W. K. A. C. (2015). Travel Motives, Perception & Satisfaction. Germany: Scholars Press.

- Haralambopoulos, N. & Pizam A. (1996). Perceived impacts of tourism: the case of Samos. Annals of Tourism Research, 23, 503–526.

- Herbert, D. (2001). Literary places, tourism and the heritage experience. Annals of Tourism Research, 28 (2), 312–333.

- Institute of Museum Services, National Endowment for the Arts, National Endowment for the Humanities, President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities (1995). Cultural Tourism in the United States: A Position Paper for the White House Conference on Travel and Tourism.

- International Council on Monuments and Sites. (1999). International Cultural Tourism Charter: Managing Tourism at Places of Heritage Significance. Mexico: ICOMOS 12th General Assembly.

- Johnson, J., Snepenger, D. & Akis, S. (1994). Residents’ perceptions of tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research, 21 (3), 629-637.

- Jurowski, C., Uysal, M. & Williams, D. R. (1997). A theoretical analysis of host community resident reactions to tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 36 (2), 3-11.

- Khunou, P. S., Reynish, N., Pawson, R., Tseane, L., Wasung, N. & Ivanovic, M. (2009). Tourism Development I: Fresh Perspective, Cape Town, South Africa: Pearson Educational and Prentice Hall.

- King, B., Pizam, A., & Milman, A. (1993). Social impacts of tourism:: Host perceptions. Annals of Tourism Research, 20(4), 650-665. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(93)90089-L

- Kreag, G. (2001). The Impacts of Tourism. Available at http://www.seagrant.umn.edu/tourism/pdfs/ImpactsTourism.pdf. Retrieved on 22 January 2015.

- Lankford, S. V. & Howard, D. R. (1994). Developing a tourism impact attitude scale. Annals of Tourism Research, 21, 121-139.

- Lankford, S. V. (1994). Attitudes and perceptions toward tourism and rural regional development. Journal of Travel Research, 32, 35-43.

- Liu, J. & Var, T. (1986). Resident attitudes toward tourism impacts in Hawaii. Annals of Tourism Research, 13 (2), 193-214.

- McCool, S. F. & Martin, S. R. (1994). Community attachment and attitudes toward tourism development, Journal of Travel Research, 32 (2), 29-34.

- Mok, C., Slater, B. & Cheung, V. (1991). Residents’ Attitudes towards Tourism in Hong Kong. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 10 (3), 289–293.

- Nayomi, G. & Gnanapala, W. K. A. C. (2015). Socio-Economic Impacts on Local Community through Tourism Development with Special Reference to Heritance Kandalama. Tourism, Leisure and Global Change, 2, 57 - 73.

- Pathirana, D. P. U. T. & Gnanapala, W. K. A. C. (2015). Tourist Harassment at Cultural Sites in Sri Lanka. Tourism, Leisure and Global Change, 2 (1), 42 - 56.

- Perdue, R. R., Long, P. T. & Allen, L. R. (1990). Residents support for tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research, 17 (4), 586-599.

- Perez, E. A. & Nadal, J. R. (2005). Host community perceptions; a cluster analysis. Annals of Tourism Research, 32 (4), 925 - 941.

- Pizam, A. & Milman, A. (1984). The social impacts of tourism. UNEP Industry and Environment, 7 (1), 11-14.

- Poria, Y., Butler, R. & Airey, D. (2004). Links between Tourists, Heritage, and Reasons for Visiting Heritage Sites. Journal of Travel Research, 43: 19-28.

- Richards, G. (1996). Cultural Tourism in Europe. Wallingford: CAB International.

- Riolta Sri Lanka Holidays, (2007). Cultural Triangle. Retrieved from http://www.mysrilankaholidays.com/cultural-triangle.html

- Robinson, C. W. (2003). Risks and Rights: The Causes, Consequences, and Challenges of Development-Induced Displacement. Washington DC: The Brookings Institution- SAIS Project on Internal Displacement.

- Robinson, M. (1999). Cultural Conflicts in Tourism: Inevitability and Inequality. Tourism and Cultural Conflicts. CAB International. p. 1-32.

- Rosenow, J. E. & Pulsipher, G. L. (1979). Tourism, the good, the bad and the ugly. Lincoln: Century Three Press.

- Ross, G. F. (1992). Resident perceptions of the impact of tourism on an Australian city, Journal of Travel Research, 30, 13-17.

- Sandaruwani, J. A. R. C. & Gnanapala, W. K. A. C. (2016). The Role of Tourist Guides and their Impacts on Sustainable Tourism Development: A Critique on Sri Lanka. Tourism, Leisure and Global Change, 3, 62 - 73.

- Sathiendrakumar, R. & Tisdell, C. (1989). Tourism and economic development of the Maldives. Annals of Tourism Research, 16 (2), 254-269.

- Sharma, P. (2013). Lucknow: The Synonym of Culture. SIT Journal of Management, 3 (2), p. 134-146.

- Sharpley, R. (1994). Tourism, Tourists and Society. Huntingdon: ELM Publishers.

- Sirakaya, E., Teye, V. & Sonmez, S. (2002). Understanding residents’ support for tourism development in the Central Region of Ghana. Journal of Travel Research, 41 (1), 57–67.

- Sunlu, U. (2003). Environmental impacts of tourism. In Local resources and global trades: Environments and agriculture in the Mediterranean region (eds. D. Camarda and L. Gras-sini) pp. 263-270. Bari: CIHEAM (Options Méditerra-néennes: Série A. Séminaires Méditerranéens. No 57). Conference on the Relationships between Global Trades and Local Resources in the Mediterranean Region, 2002/04. Rabat, Morocco. Available at http://om.ciheam.org/om/pdf/a57/04001977.pdf. Retrieved on 3 March 2015.

- The Island. (2015). Challenges of tourism industry in Sri Lanka - Travel, available at http://www.island.lk/index.php?page_cat=article-detailsandpage=articledetailsandcode_title=35614

- Timothy, D. & Boyd, S. (2003). Heritage Tourism. Harlow: Prentice Hall.

- Tosun, C. (2002). Host perceptions of impacts: A Comparative Tourism Study. Annals of Tourism Research, 29 (1), 231–253.

- UNESCO (2015). UNESCO world heritage list. Available at http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/

- UNWTO (2008). International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics. Draft Compilation Guide Madrid, March 2011 Statistics and Tourism Satellite Account Programme. 121 p. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/tradeserv/egts/CG/IRTS%20compilation%20guide %207%20march%202011%20-%20final.pdf

- UNWTO (2014). UNWTO Tourism Highlights. 2015 Edition. Retrieved from http://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284416899.

- Upchurch, R. S. & Teivane, U. (2000). Resident perceptions of tourism development in Riga, Latvia. Tourism Management, 21, 499-507. http://www.kdmp.gov.tr, 2015, http://www.wwf.org.tr, 2015.

- Virginia Department of Historic Resources. (1998). Tourism Handbook: Putting Virginia’s to Work. Richmond.

- Williams, S. (1998). Tourism Geography. London. Routledge.

- World Tourism Organization and European Travel Commission. (2005). City Tourism and Culture – The European Experience. Retrieved on March 30, 2015 from www.etccorporate.org/resources/uploads/ETCCityTourism&Culture_LR.pdf