The Dance of Poverty and Education for Childhood Nutritional Victimization in Bangladesh

Md. Abdul Hakim1, Md. Kamruzzaman2, *

1School of Food Technology and Nutritional Science, Mawlana Bhashani Science and Technology University, Tangail, Bangladesh

2School of Victimology and Restorative Justice, Institute of Social Welfare and Research, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Abstract

Nutritional victimization in childhood is going spiral in view of a global health threat as in Bangladesh as the children are not aware of importance of taking balanced diet in order to their ongoing pauperism across the country. They cannot achieve proper education as a passive affect of their poverty as well. The primary aim of the study is to highlight the nutritional victimogenesis engulfing the societies. The secondary aim is the verbal sketching of the workflow for reducing childhood victimization across different societies in Bangladesh.

Keywords

Nutritional Victimization, Childhood, Education and Poverty, Socio-Economic Status, Bangladesh

Received:May 18, 2016

Accepted: July 11, 2016

Published online: August 5, 2016

@ 2016 The Authors. Published by American Institute of Science. This Open Access article is under the CC BY license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

1. Introduction

Children are the kids aged less than 18 years ages coming to fight to gild the globe aiming to adapt a decent life as the globe is their habitual abode [1-3]. The facing of nutritional victimization in childhood in a big headache in the world now-a-days due to deprivation of getting educational opportunities because of the giant poverty by name in the developing countries [4-9]. About 1.3 million children and infants die in developing countries and the greater bulk of these deaths are linked to malnutrition [10] and malnutrition is the largest single contributor to child mortality in the developing countries [11-13]. Nearly 4 of each 5 malnourished children in South - East Asian region and it is now documented to occur 83% of child deaths are attributed to mild to moderate malnutrition [14,15]. Childhood malnutrition leads to stunted growth and enlarged morbidity and mortality which decrease the survival chances of adults in later life span and intellectual and spiritual development [16-19]. There are only few studies found on the topic related studies in abroad denying any study in Bangladesh, the South Asian developing country in the previous years and therefore the current study is conducted to focus the poverty and educational background in care of nutritional victimization offenders to affect the upright childhood in Bangladesh.

2. Poverty and Nutritional Victimization

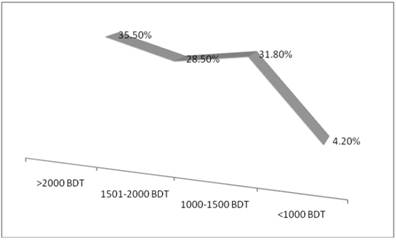

Bangladesh is an agricultural country and around 2/3rd of the population are the earners of their income from agriculture. The crops were destroyed at yearly flooding session leads their life in a misery condition depriving of adequate health care, water, shelter and sanitation [20-23]. They cannot give proper support to their children and hence a big portion of them are turned into the thrown away children. They migrate to rural areas to gain their economic support to earn their foods and other essentials [24,25]. Of them, about 35.5% children are able to earn >2000 BDT and about 4.2% are <1000 BDT per month living their life as a homeless kids in different streets, factories and other informal works to manage two times meals (light meals) by 15%of them [26].

Figure 1. Earning of thrown away children in Bangladesh [26].

3. Education and Nutritional Victimization

The parents are mostly illiterate working as farmers and other lower class works in the societies in various topographic sites in Bangladesh. The parents cannot but making their children as an earning member of their family due to their not being educated and they cannot give their children the proper education facilities [27-29]. The education level improves the nutritional condition of the children [6, 17 and 30-32].

4. Nutritional Victimization Influencing Factors

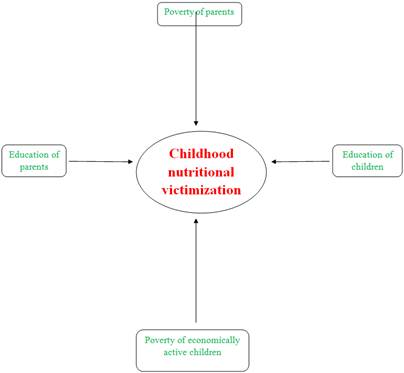

There are different social, cultural, religious, demographic, topographic, seasonal, environmental and many others confounding factors to create child victimization in nutritional arena [33-35]. The basic causes of childhood nutritional victimization are as sketched in the figure 2 as a complex network of different factors to hit upon the nutritional victimogenesis [36,37].

Figure 2. Basic measures to accelerate nutritional victimogenesis during childhood.

5. Discussion

This study is done in a South Asian developing country Bangladesh by name in the world as rule as availability of sample. Nutritional victimization is the state of depriving complete physical, mental, social and spiritual well-being [38] of the population at the societies in the country. To choose the right foods in hygienic way is the key to the observance of healthy life and the children are not able to choose right foods considering nutrients or other food associated substances which can make them healthy and sometimes they are at bay to eat the right foods paying concentration on rumors because they do not know how to consume foods by further processing using easy tricks to make the foods safe for consumption [39-41]. They are not provided constitution approved nutritional facilities at all in Bangladesh [42,43]. The nutrients consuming in the body supports the growth and development, health and nutritional care and physical and mental activities and help to prevent diseases [44-47]. The spatial microsimulation modelling [48-50] can be a constructive bid in designing policies and see any governments and NGOs, environmental and spatial effects across different sites [51-53] in the country as these tools are in galore application in most of the developed countries for observing nutritional soundness of children curbing the health confounding factors to eradicate malnutrition by 2020: an Agenda for Change in the Millennium [54,55].

6. Conclusion

Childhood malnutrition is the largest public health threat in developing countries like Bangladesh. The present study upshot revealed that nutritional victimogenesis is a multi-dimensional threat correlated to socioeconomic and demographic traits; mostly relied on educational background and observed pauperism of the concerned population. So the think tank should come up with splashing bid in order to overcome these sad tales. Future research should move further to investigate the problems aiming to implement different measures to curb the health, hygiene and nutritional confounding effects. Microsimulation modelling methods should be also explored in future studies for the policy designing and implementing to shirk nutritional victimization in the country.

References

- Hakim MA and Rahman A. Health and Nutritional Conditionof Street Children of Dhaka City: An Empirical Study in Bangladesh. Science Journal of Public Health 2016; 4 (1-1): 6-9.

- UNICEF. Street Children, 2007.Available at http:/www.unicef.org.

- Sumon AI. Informal Economy in Dhaka City: Automobile Workshop and Hazardous Child Labor. Pakistan Journal of Social Sciences 2007; 4(6): 711-720.

- Hakim MA. Nutritional Status and Hygiene Practices of Primary School Goers in Gateway to the North Bengal. International Journal of Public Health Research, 2015; 3 (5): 271-275.

- Weitzmawqn M. Excessive school absences. Advances Develop Behav Pediar 1987; 8: 151-78.

- Hakim MA, Talukder MJ and Islam MS. Nutritional Status and Hygiene Behavior of Government Primary School Kids in Central Bangladesh. Science Journal of Public Health 2015; 3 (5): 638-642.

- Kamruzzaman M and Hakim MA. Socio-economic Status of Child Beggars in Dhaka City.Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities2015; 1(5): 516-520.

- Kuddus A andRahman A. Affect of Urbanization on Health and Nutrition, International Journal of Statistics and Systems2015; 10(2): 164-174.

- Hakim MA and Talukder MJ. An Assessment of Health Status of Street Children in Tangail, Bangladesh. Science Journal of Public Health2016; 4 (1-1): 1-5.

- Rahman A and Chowdhury S. Determinants of chronic malnutrition among preschool children in Bangladesh. Journal of Biosocial Science 2007; 39 (2): 161-173.

- Rahman A and Hakim MA. Malnutrition Prevalence and Health Practices of Homeless Children: A Cross-Sectional Study in Bangladesh. Science Journal of Public Health 2016; 4 (1-1): 10-15.

- Megabiaw B and Rahman A. Prevalence and determinants of chronic malnutrition among under-5 children in Ethiopia. International Journal of Child Health and Nutrition 2013; 2 (3): 230-236.

- Rahman A, Chowdhury S, Karim A. and Ahmed, S. Factors associated with nutritional status of Children in Bangladesh: A multivariate analysis. Demography India 2008; 37 (1): 95-109.

- UNICEF. Malnutrition in South Asia. A Regional Profile, UNIEF report (November), 1997; p. 8.

- Rahman A, Chowdhury S and Hossain D. Acute malnutrition in Bangladeshi children:levels and determinants. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health 2009;21 (3): 294-302.

- Hakim MA and Kamruzzaman M. Nutritional Status of Preschoolers in Four Selected Fisher Communities. American Journal of Life Sciences 2015; 3 (4): 332-336.

- Rahman A. Significant Risk Factors for Childhood Malnutrition: Evidence from an Asian Developing Country.Science Journal of Public Health2016;4 (1-1): 16-27.

- Nandy S, Irving M, Gordon D, Subramanian SV and Smith GD. Poverty, child under nutrition and morbidity: new evidence from India. Bull WHO, 2005; 83: 210-16.

- Rahman A and Biswas SC. Nutritional status of under-5 children in Bangladesh. South Asian Journal of Population and Health2009; 2 (1): 1-11.

- Rahman Aand Kuddus A. Effects of some sociological factors on the outbreak of chickenpox disease, JP Journal of Biostatistics, 2014; 11 (1): 37-53.

- Nazrul I. Socioecological perspective of poverty. Bangladesh e-journal of Sociology 2010; 7(2): 57-60.

- Kamruzzaman M and Hakim MA. Family Planning Practices among Married Women attending Primary Health Care Centers in Bangladesh. International Journal of Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering 2015;1 (3): 251-255.

- Kamruzzaman M and Hakim MA. Livelihood Status of Fishing Community of Dhaleswari River in Central Bangladesh. International Journal of Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering 2016; 2(1): 25-29.

- Bhandari S and Banjara MR.Micronutrients Deficiency, a Hidden Hunger in Nepal:Prevalence, Causes, Consequences, and Solutions. International Scholarly Research Notices Volume 2015(2015,Article ID 276469, 9 pages.

- UNICEF, ILO, WB. Understanding Children’s Work in Bangladesh, 2009.

- Hakim MA and Kamruzzaman M. Nutritional Status of Central Bangladesh Street Children. American Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Research 2015; 2 (5): 133-137.

- Rahman A and Sapkota M. Knowledge on vitamin A rich foods among mothers of preschool children in Nepal: impacts on public health and policy concerns, Science Journal of Public Health, 2014; 2(4): 316-322.

- UNICEF. Every last child. Fulfilling the Rights of Women and Children in East Asia and the Pacific, 2001.

- ILO. Working out of poverty. International labor office, Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Russel-Mayhew S, McVey G, Bardick A and Ireland A. Mental Health, Wellness, and Childhood Overweight/Obesity. The Journal of ObesityVolume 2012(2012), Article ID 281801, 9 pages.

- Bhuiya A, Wojtyiak B, D’Suzoa S and Zimili S. Socio-economic determinants of child nutritional status: boys versus girls. Food Nutr Bull 1986; 8(3): 3-7.

- Bulbul T and HoqueM. Prevalence of childhood obesity and overweight in Bangladesh: findings from a countrywide epidemiological study. BMC Pediatr 2014; 14: 86.

- Pellet PL. Malnutrition, Wealth and Development. Food Nutr Bull 1981; 31:17-19.

- D’Suzoa MR. Housing and Environmental Factors and their Effects on the Health of Children in the Slum of Karachi, Pakistan. J. Biosoc. Sci. 1997; 29: 271-281.

- Ayaya, S. and Esami, F. (2001) Health problems of homeless children in Eldoret, Kenya, East African Medical Journal, 78 (12): 624-9.

- Karmen A. Crime Victims: An Introduction to Victimology, Wardsworth Publishing, 1984; p. 35-38.

- Rahman MA, Rahman SM, Haque NM and Kashem MB. A Dictionary of Criminology and Police Science, 2009; p. 267.

- WHO. Constitution of the World Health, 2006.

- Linkon KKMR, Prodhan UK, Hakim MA and Alim MA. Study on the Physicochemical and Antioxidant Properties of Nigella Honey. International Journal of Nutrition and Food Sciences 2015;4 (2):137-140.

- Hakim MA. Trick to get rid of formalin. Available at http://www.thedailystar.net/trick-to-get-rid-of-formalin-58341. (Accessed on January 4, 2015).

- Hakim MA. Physicochemical Properties of Dhania Honey. American Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Research2015; 2 (5): 145-148.

- Hakim MA. Nutrition on malnutrition helm, nutrition policy in fool's paradise.Available at http://www.observerbd.com/2015/09/20/111732.php (Accessed on September 20, 2015).

- Whitney E and Rolfes S. Understanding Nutrition (Tenth edition), 2005; p. 6.

- Kumah DB, Akuffo KO, Abaka-Cann JE, Affram DE and Osae EA. Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity among Students in the Kumasi Metropolis. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism Volume 2015(2015),Article ID 613207, 4 pages.

- Murphy, S.P., Allen, L.H. (2003). Nutritional importance of animal source foods. J Nutr, 133: S3932-5.

- Rahman A. Small area estimation through spatial microsimulation models: Some methodological issues, Paper presented at the 2nd General Conference of the International Microsimulation Association, The National Conference Centre Ottawa, Canada,2009; p. 1-45 (June 8 to 10).

- Kamruzzaman M. Child Victimization at Working Places in Bangladesh. American Journal of Applied Psychology 2015,4(6): 146-159.

- Rahman A and Harding A. Social and health costs of tobacco smoking in Australia: Level, trend and determinants.International Journal of Statistics and Systems2011; 6(4): 375-387.

- Phil M. Small area housing stress estimation in Australia: Microsimulation modelling and statistical reliability, University of Canberra, Australia, 2011.

- Islam D, Ashraf M, Rahman A and Hasan R. Quantitative Analysis of Amartya Sen's Theory: An ICT4D Perspective. International Journal of Information Communication Technologies and Human Development 2015;7(3): 13-26.

- Islam MS, Hakim M A, Kamruzzaman M, Safeuzzaman, Haque MS, Alam MK. Socioeconomic Profile and Health Status of Rickshaw Pullers in Rural Bangladesh.American Journal of Food Science and Health2016, 2(4):32-38.

- Rahman Aand Upadhyay S.A Bayesian reweighting technique for small area estimation. Current Trends in Bayesian Methodology with Applications, CRC Press, London, 2015; p. 503-519.

- Rahman A,Harding A, Tanton R and Liu S. Simulating the characteristics of populations at the small area level: New validation techniques for a spatial microsimulation model in Australia, Computational Statistics and Data Analysis2013; 57(1): 149-165.

- Kamruzzaman M and Hakim M A. Socio-economic Status of Slum Dwellers: An Empirical Study on the Capital City of Bangladesh, American Journal of Business and Society2016, 1(2): 13-18.

- Ending Malnutrition by 2020: an Agenda for Change in the Millennium. Final Report to the ACC/SCN by Commission on the Nutrition Challenges of the 21st Century, February 2000.