Factors That Promote Students Sexual Abuse in Ghana

Anthony Bordoh1, *, Isaac Eshun1, Shani Osman2, Patrick Kwarteng3, Sophia Andoh4, Theophilus Kweku Bassaw5, Joseph Kweku Prah6

1Department of Arts and Social Sciences, Enchi College of Education, Enchi, Ghana

2Department of Arts and Social Sciences, Tumu College of Education, Tumu, Ghana

3Department of Arts and Social Sciences, Wiawso College of Education, Sefwi Wiawso, Ghana

4Department of Arts and Social Sciences, Holy Child College of Education, Takoradi, Ghana

5Department of Arts and Social Sciences, Komenda College of Education, Komenda, Ghana

6Social Sciences Department, Kwegyir Aggrey Senior High School, Anomabo, Ghana

Abstract

Senior high schools students have faced a lot of sexual abuse due to unnoticed factors. This study examined the factors that has promoted sexual abused of students in public senior high schools in Ghana. The research was conducted in four (4) different public senior high schools in the Mfantsiman Municipality as one case study. Simple size of 403 students and 20 teachers as participants were employed for the study, simple random sampling and purposive sampling techniques were used to select the respondents. A structured questionnaire was used to solicit data from the respondents. The data were presented in the form of percentages and frequency tables to facilitate clearer and easier interpretation of results for the presentation of findings. The factors that have promoted the sexual abuse of students includes: age, gender, care arrangement / parental absence, parental substance abuse, parental level of education, school and schooling environment, socio-demographic risk and poor parent-child relationship. It is recommended that Programmes aimed at alleviating household poverty in the districts should be extended to cover many more households. Furthermore, the Ghana Education Service should be strengthening Institutions at District Level, in other words, Parents, community opinion leaders and institutions such as Police, District Assembly, Health workers, Teachers etc. identified as first point of contact when a student is sexually abused should be trained on how to identify and handle such forms of abuse cases.

Keywords

Factors, Promotes, Sexual, Abuse, Sexual Abuse, Students, Senior High Schools (SHS’s), Central Region, Ghana

Received:June 30, 2016

Accepted: August 24, 2016

Published online: September 8, 2016

@ 2016 The Authors. Published by American Institute of Science. This Open Access article is under the CC BY license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

1. Introduction

This paper presents the out of the factors that promote sexual abuse in Ghana. The paper is structured into five (5) main sections, namely; the introduction, review of the literature, methodology, findings and discussion and the conclusion. The first section introduces the structure of the paper, the context and aims and objectives of the paper. The literature review section reviews the relevant literature on factors promoting sexual abuse among students. The methodology section presents a broad description of the methodology and procedures adopted in the conduct of the study on sexual abuse of students in public senior high schools. Findings resulting from the study are presented and discussed in the section following the methodology and conclusion, highlighting on some implications of the findings, and recommendation.

[41], everyday parents send their children off to school confident that teachers and administrators will not only teach them but also ensure the safety of their environment. They go further to suggest that most people believe whatever the failings of our schools, the people employed in them will not hurt our children. This is the ideal professional mandate of teachers, but the researcher holds a contrary view on this opinion; while most professionals in schools can be trusted not to harm students, this is not true of all of them. Newspaper accounts reveal in lurid details what can happen to students when a sexual offender works in a school.

Sexual abuse of students is perceived to be a problem by various professional groups including the Police Service, Civil Society Organizations, Criminal Courts, Child Welfare Agencies, Teachers, as well as the general public. According to [29], sexual abuse of children specifically students is morally wrong especially because students have rights, one of which is to be free from maltreatment of a sexual kind. There is also a shared desire to assure the safety of vulnerable people, including students. Sexual abuse has not been systematically addressed because this issue is woefully under-studied. While we have scanty data on incidence and even less on description of predators and targets, newspapers and other media coverage have prodded some school authorities, educators and others to acknowledge that sexual abuse is still occurring.

Recent findings by the UN suggest that sexual abuse within schools is a widespread but largely unrecognized problem in many countries. According to the views of [32], the closed nature of the school environment means that students can be at great risk of sexual abuse in schools. According to [32], in Ghana, there is a sexual abuse problem in our schools. They revealed in their study that, 27% of the female students had been propositioned by their school teachers. This assertion is buttressed by the statistics provided by the state agencies. According to the Annual Report of [20], 622 persons were convicted for defilement in 2007. Out of this figure, Eastern Region had (181), Ashanti (155) and Central (120) cases. The Domestic Violence Victims Support Unit (DOVVSU) of the Ghana Police Service, on the other hand, reported that cases of defilement rose from 449 in 2007 to 552 in 2008 (DOVVSU Annual Report, 2008). These studies give enough indication that sexual abuse is a menace in which student and children suffer within the school environment, be it from their mates, teachers and school workers.

It must be recognized that there are enough documentations in form of policies, acts and regulations that seek to protect and safeguard students from sexual abuse. These include the 1992 Constitution of Ghana, the Children’s Act 1998 (Act 560) of the Republic of Ghana, the Criminal Code (Amendment) Act 1998 (Act 554) and the Code of Professional Conduct of the Ghana Educational Service. Each document defines various aspects of sexual offences and penal measures for offenders. Specifically, the Code of Professional Conduct of the Ghana Educational Service (GES) indicates what can be termed sexual abuse of student within any educational institution. This document makes it clear in section 53 that no employee shall indulge in immoral relationship with a pupil or student in any educational institution. The code further provides the necessary disciplinary measures against those who go contrary to the Code of Professional Conduct of the Ghana Educational Service (GES). Disciplinary measures include: Deferment of increment that is, postponement of the date on which the next increment is due with corresponding postponement in subsequent years; reduction in rank or of salary; suspension that is, loss of pay and allowances for a period not exceeding two years; removal from the GES- that is termination of appointment with full or reduced retirement benefits; termination striking of name from the register of teachers; that is, withdrawal of one’s certificate or license to teach with consequent termination of appointment for good [19].

The purpose of this paper was to ascertain the factors that promote sexual abuse in the public senior high schools in Ghana. The research was guided by this question- What are the factors that promote student sexual abuse in public senior high schools in the Mfantsiman Municipality? The research covered the four (4) senior high schools in the Mfantsiman Municipality in the central region of Ghana.

2. Literature Review on Factors That Promote Students Sexual Abuse in Schools

According to [47], from the information available to their department is obvious that sexual abuse takes various factors and is perpetrated by both learners and staff in schools. It ranges from sexual harassment, touching and verbal degradation to rape and other forms of sexual violence. This abuse takes place in dormitories, in empty classrooms, in hallways and in school toilets. And while all learners may be victims to abuse, girls and disabled learners are particularly vulnerable. Age as a factor that promotes student sexual abuse in schools, culminating evidence suggests boarding school to be sites for violence. Girls whose basic provisions were unmet were particularly vulnerable. In order to sustain themselves, they accepted "gifts" which potentially lend them to be victims of sexual abuse. One girl who finally dropped out of school due to pregnancy explained; “Most of the girls are from a rich family. They come with good things and yet some of us do not have, so one is forced to look for a boyfriend to supplement. When I got a boyfriend I never lacked even one thing(Girl, 15 years). Lack of basic needs therefore acts as a factor that creates a conducive atmosphere for sexual abuse to occur. It is fuelled by a salient expectation/ acceptance that girls can use their sexuality to benefit either themselves or their families. Instances were recorded where parents expect children to bring provisions home and did not interrogate where and how the children got the items [11]. This clearly posits that the perpetrators of sexual abuse do not consider the age factor at all when abusing the victims. This factor was also supported by research done by [5], and found out that the 1,194 new clients presented for treatment at a child sexual abuse clinic in Harare between 2004 and 2005, 90% were female and ranged in age from 15 years to 16years, 93% and 59% of the girls and boys respectively were classified clinically as pre-pubertal.

This study indicates that female student suffer more sexual abuse in schools than their male counterparts. To female students the society is an unfair environment because of the many violent encounters they face due to their minority and their social role. This idea is supported by an assertion made [3]. In their conclusion to the societal attitude to violence against women and children, they say that violence against women and children is perpetrated in a wide range of relationships family, sexual, authority such as schools and workplace. The researcher goes further to indicate that in all these relationships children and women are powerless against men and violence is the result of men’s inordinate power over them. It is clear that their powerlessness stems directly from the view of women as minors [3].

Global School-Based Student Health Survey from five Sub-Saharan African countries confirmed the prevalence of sexual abuse across all age sub-groups studied: the percentage of girls who reported ever being physically forced into sexual intercourse was 22% for 13 years and under 14 years old, and ranged from 27%for the 15year old and 29% for those 16 years and older. For boys, the percentages reported were highest among the 13 years and under sub-group (24%), lowest for the 14 year olds (17%), 22% for 15year olds and 21% for those 16years and older [8]. The above study is confirmed by the study conducted by [3]. According to this study 71% of adolescent female students who are under school going age had suffered some form of sexual abuse. The reason why age becomes a factor in student sexual abuse could be that, at the age of 13 to 17, the student would have developed into adolescent or a teenager with physical body development and good appearance.

A research conducted in Chad Republic indicates that cases of sexual abuse and sexual exploitation rarely come to the attention of the authorities, nevertheless, the available information indicates that 4 in 10 cases reported, it involved young girls aged 13 to 17 years, and more than 25% involved children aged 10 to 12 years [49]. The study portrays that most of the sexual abuse involves young girls; on the other hand, a small percentage of boys had been victims of sexual abuse in one form or the other. Reading through these materials, it is clear that age has been one of the factors that perpetrators of sexual abuse consider before mounting their action on their victims has greatly affected the gender role in the community.

Another critical factor that promotes sexual abuse in senior high schools is the gender or sex of the victim (boy /girl). The term 'sexing' recognizes that male and female bodies have specific cultural meanings at both an individual and institutional level at the same time as it eschews an essentialist view of sexual differences. Thus, the term 'sexed' embraces the cultural meanings that are ascribed to the sexual characteristics of different bodies. Like gender, sexing is recognized as both an historical and cultural process and, as such, employs a social constructionist method [30]. This means that sexing and gender are different ways of conceptualizing men and women as social subjects. In other words, both sex and gender are understood to be social constructs [13] & [30]. Indications are that both sexes do suffer one form of sexual abuse or the other in their lives, but the issue is that female student faces more sexual abuses than their male counterpart.

According to the [24], forcing or enticing a child or young person to take part in sexual activities, not necessarily involving a high level of violence, whether or not the child is aware of what is happening. The activities may involve physical contact, including assault by penetration (for example, rape or oral sex) or non-penetrative acts such as masturbation, kissing, rubbing and touching outside of clothing. They may also include non-contact activities, such as involving children in looking at, or in the production of, sexual images, watching sexual activities, encouraging children to behave in sexually inappropriate ways, or grooming a child in preparation for abuse (including via the internet). Sexual abuse is not solely perpetrated by adult males. Women can also commit acts of sexual abuse, as can other children [19] due to the parental absence in their various household.

One important issue that serves as a platform for studentsto be sexually abused in schools is the kind of living arrangement or parental absence in the society. According to [17], little work has been done on studentsliving arrangements and parental absence. However, research undertaken in Sub-Saharan Africa in the last few years shows that students who found themselves in this situations were nearly one and half times more likely to have had sex than those students who live with both biological parents, and were more likely to have had sex by age 15 years [47]. The situation is such that students who live with both parents were less likely to have had sex than students who live with one or neither parent [5]. Another study done by [12], reported a relationship between parental absence and history of student sexual abuse in schools. Noted that being raised without one’s father, or living apart from one’s mother for a significant part of one’s childhood, have been associated with sexual abuse. Living with one biological parent has been found to be related to sexual abuse consistent with other studies. A study conducted in South Africa by [28] shows that adolescents who were not living with a biological father reported an increased risk of teenage pregnancy in their schooling. The findings suggests that parental figures can play an important role by providing greater control and restrictions on youth risk behaviour which may lead to a lesser likelihood of increased protection from potential perpetrators.

However students who do not leave with their parent’s abuse them sexually, on the same vain parents who also abuse drugs abuse their own children. [21] posits that children of parents who misuse substances may have homes where lots of adults are coming and going or they may be left alone for long periods of time while their parents are out.

This can leave those children vulnerable especially when the adults in the house may be under the influence of drugs or alcohol. This finding is further supported by studies which have reported that mothers of those sexually abused students are less likely to have finished high school [1]. Proper comparison of both studies shows that parental low education level was linked to increased risk for sexual abuse among students. This is possible because parental successful academic experiences may play a protective role in preventing sexual victimization among their children. A possible explanation is that educated parents are likely to make use of suggested prevention programmes and other available resources. The measures and programmes could help students to guard against any signs of sexual abuse perpetrator. On other hand, parent with lower educational level may not be aware of the suggested prevention programmes that will aid his/her children when it comes to sexual abuse in their schools.

Many African students are at risk of experiencing sexual abuse in their immediate environments- their own homes and communities, including schools. In the views of [39], school and schooling environment is a contributing factor to the student sexual abuse phenomena. Student sexual abuse in school settings is described by many writers and researchers in the region as a serious problem which mostly impacts on girls, but not exclusively. They go on to suggest that school environments are high-risk locations for student sexual abuse, even though homes were found to be riskier [39]. An observation made by [45] indicates that student sexual abuse in school settings involves sexual favours in exchange for good grades as well as transactional sex where the victim is coerced into sexual activity in return for educational benefits such as school fees and material things. It must be understood that this kind of sexual abuse where perpetrators of sexual abuse or caregivers take advantage of their students and trade with them for sex gains in return give out grades and materials things is obviously against the basic fundamental human rights of students. The basic human rights of these students are that: no employee of a school shall indulge in immoral relations or have sexual intercourse (either with or without consent of the student) with a pupil or student in pre-tertiary public or private institution [20]. This simply implies that students should not be discriminated against on any grounds for sex or any other benefits without their natural consent. A situation where victimsright of consent is subdued due to power differentials and material considerations are put first for any sexual gains really undermines the basic rights and freedoms of victims of sexual abuse.

According to [37], this phenomenon where teachers trade grades, a school fees and material things in return for sex with students happens most times in secondary schools. For instance, [37] has identified the concept of “Sexually Transmitted Marks This is the latest trend from educational institutions where students and teachers are exchanging a lot more than knowledge and information. [37] has noted that teachers are soliciting sexual favours from students in exchange for better academic pass marks in their respective courses. These sexual abuse favours include non-consensual, unwanted touching, sexual kissing, fondling and other forms of sexual harassment [37]. It is a perception that school workers are considered to be right at all times and this undermines the fair hearing procedure in our democratic dispensation. In the schooling community teachers and workers are given authority to teach, mark studentsacademic work and teachers are allowed to make promotions and repetitions as well as punish and reward student for their actions and inactions without any external supervision and monitoring. In the view of the researcher teachers at times exercise these responsibilities in a whimsical and capricious manner without reference to human rights and freedoms of these students. They at times in turn solicit sexual favours from students in exchange for their own basic responsibility which at times leads to non-consensual sexual activities with the students [37].

[49] has observed that in West and Central Africa sexual abuse in school settings occur in all regions; they suggest that teachers were found to be seducing school girls in 21 of the 22 countries studied; verbal harassment of school girls by school boys was identified as a problem in 20 of the 22 countries and sexual favours in exchange for marks was prevalent in 20 of the 22 countries [49]. Findings from the study give concern to every gender activist and student protection agency. This is because the studies show that female students are at high risk of being sexually abused by teachers. This assertion has been confirmed by [50]. The study indicated that ministries of education were aware of the problem where teachers abuse female students sexually and considered it to be one of the main reasons why girls drop out of school.

[27] opines that there is high level of sexual abuse of girls in secondary schools, but reports that while male teachers use various methods and opportunities to gain sexual access to the learners in their schools, this does not necessarily occur in school toilets. However, this act normally occurs at the dark corners within the school environment. They go further to indicate that female students can be raped in school toilets, empty classrooms, dormitories and hostels by teachers due to the facts that schools are full of darkness, bushier areas and corners as well as the power and control teachers have to search and punish students.

Another aspect in which the school environment act as a risk factor for sexual abuse of students are the distance to school and school practices. A considerable amount of sexual abuse occurred when learners are in the process of going to school. For instance in the school system spaces such as the bush around the school were preferred venues of abuse while in most schools road transport, the hostels and boarding systems were recipe for sexual abuses in the school [11]. One critical school practice that needs attention, according to the researcher, is the practice where students need to travel to school early to beat time for morning study time and leave after evening study exacerbated the situation. According to the researcher, the issue of morning and evening study allocations need re-examination because of the threats to student safety. Female students whose basic provisions were unmet were particularly vulnerable to sexual abuse by perpetrators of the act. In order to sustain themselves, they accept “gifts" which potentially lend them to be victims of sexual abuse. Lack of basic needs or unemployed parent therefore acts as a cause that creates conducive atmosphere for student sexual abuse in schools. It is fuelled by a salient expectation or acceptance that girls can use their sexuality to benefit themselves [11].

A review of socio-demographic risk factors of parents and sexual abuse of a student is based on a retrospective community study in the USA by [6] the study revealed that parental occupational status was moderately related to having a student who will be sexually abused. In the same vein, unemployment has been reported as a risk factor for sexual abuse, unemployed parent would not be able to meet the needs of his or her ward in school. According to Chege and Sifuna [11], for students to survive in school, they accept gifts which potentially lend them to be victims of sexual abuse, in other words, lack of basic needs therefore acts as a cause that creates conducive atmosphere for student sexual abuse in schools. One prospective study suggested that student who had experienced sexual abuse often grew up with parents who were unemployed [26]. Unemployment may affect risk factors through the stress of reduced material resources a sense of powerlessness in the unemployed parent or through reduced parent-child contact [4]. Maternal employment brings significant stresses into the parent-child relationship and has implications in terms of student care arrangements, but may also act as a protective factor through a range of social-psychological benefits [42].

A study conducted by [15] among female high school students in Israel indicates that higher occupational status of the father was associated with higher likelihood of sexual abuse. Such a finding is as important as it is puzzling. However, it is not clear in the findings whether daughters of fathers with high occupational status actually experience higher rates of sexual abuse or are more likely to report such abuse, for example, because they are more liberated and perhaps empowered and therefore are less likely to fear the consequences of self-disclosure such as family dishonour and they could go further to report sexual abuse cases to parents or keep quiet for fear of stigmatization. Mostly well being parents who had children out of wedlock and later welcomed them capitalized on it and abuse them sexually.

Several studies suggest that sexual abuse often takes place in non-nurturing environmental and familial contexts such as poor parent-child relationships and family stress [7]. In a study that was conducted by [2], it was noted that insecure interpersonal attachment in a family such as between a daughter and a father who seems to reject her may increase the risk of sexual abuse in that family. This finding has far reaching implications on intra-familial sexual abuse, in that, adult perpetrators like teachers who are not strongly attached to their students may have poor control of their impulses and libido towards their students. It is natural that students at times build trust and confidence in their teachers but at times teachers and workers of the school pay these students back with unwanted sexual advances.

On the other hand, non-offending parents or teachers who are not attached to their children or students respectively may not notice that the students are being sexually abused. As a result students may be more willing to submit to sexual abuse if it seems a way to build attachments they otherwise lack [25]. For instance, students may end up seeking advice from their teachers, peers, sugar daddies or mummies, who are likely to mislead and expose them to sexual abuse. [7] further argue that families characterized by considerable chaos and lack of interpersonal attachment, multiple ongoing problems and/or conflicts, students may be poorly supervised and subjected to a considerable amount of dislocation that exposes them to victimization in different contexts.

Related to the foregoing observations is that, student without secure parental relationships may also be less likely to disclose sexual abuse experiences to their parents or other adults thereby perpetuating the problem. This section of the literature review has highlighted some of the individual factors linked to the age and sex of the victims of SSA. The interpersonal and social relations with the perpetrators have been described, as well as the situations and contexts in which SSA occurs. However, some potentially useful variables, such as place of residence, whether in a rural or urban setting, child birth order, family ties, degree of social cohesion and the role of traditional systems of sexual control are largely not reflected in this literature. Literature on the factors associated with student sexual abuse, particularly with regard to school and schooling environment, level of education and income; the age level of the student and sex of the students has been thoroughly discussed in the literature review. Based on the two concepts of age and gender, society has generally agreed that student are the most vulnerable for they have to survive against a background where students are unjustly treated and taken as second class citizens in most societies and where as they solely depend on adults for survival who can choose to take care or not, provide or not provide the three basic needs of food, shelter and clothing.

3. Methodology

The study was carried out in four Senior High Schools - Saltpond Methodist Mfantsiman Girls, Mankessim, and Kwegyir Aggrey in the Mfantsiman Municipality in Central Region of Ghana as one case study. The case study determined the factors and relationships which have resulted in the current behaviour. This study adopted a multiple case study research design. The data were used together to form one case. [44] suggests that multiple case research should involve between four and ten cases for maximum benefit. This number of cases will helps researchers to not only gather enough data to provide a rich description of each case, but careful analysis of the similarities and differences between the cases can also help them gain an in-depth understanding of their focus phenomenon. The case study offered richness and in-depth of information which is not usually offered by other methods [18].

4. Findings and Discussion

This section presents the descriptive statistics of the factors responsible for sexual abuse in public senior high schools in the Mfantsiman Municipality. The perception of the respondents on factors responsible for sexual abuse in public senior high school is summarized in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. The responses from the two main respondents of this study (i.e. students and teachers) are combined in the analysis and in the interpretations.

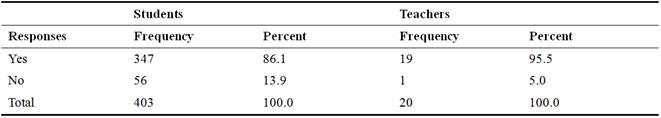

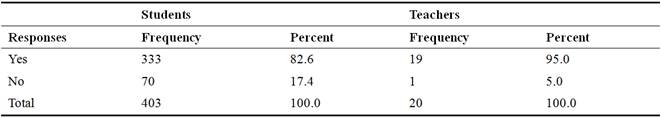

Table 1. Age and Gender.

Table 1 indicates that the large majority of the respondents, 347 students (86.1%) and 19 teachers (95%) were of the view that age and gender are some of the factors that are responsible for sexual abuse in schools. 56 students (13.9%) and 1 teacher (5%) in the sample responded that the age and gender are not factors that promote sexual abuse in schools. According to the finding of the study, a large majority of the respondents perceive that age and gender are factors that promote sexual abuse between perpetrators and the victims.

The respondents admitted that sexual abuse predominately affects those who have reached certain age within the community settings (i.e. puberty or adolescent group). It is even clearer from Table 1 that female students are more victims of sexual abuse than their male group. The opinion from the respondents is confirmed by [35] that age is one of the contributing factors that promote sexual abuse of students in public senior high schools.

Another study to buttress the views of the participants is a study conducted in Harare between 2004 and 2005. In this study, 90% were females ranging from 15 years to 16 years, 93% and 59% of the girls and boys respectively suffered sexual abuse in schools [5].

To confirm the finding of the study with regards to age as a factor in sexual abuse a case study conducted in Cote D’Ivoire by [18] with sample of 147 students revealed that 56% of the cases of sexual abuse against students were reported by students aged between 13 years to 18 years. These ages fall between secondary school going age in Ghana.

In respect to the admissions of respondents in the study about gender being a factor for sexual abuse in schools, [8] buttressed this opinion. From a Global School-Based Health Survey Data from Namibia, Swaziland, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe the odds of having been exposed to sexual abuse were greater among female students. Another study that is congruent with the views of the respondents is a compilation featured in the World Report on Violence and Health. This report showed that forced sexual initiation was higher among adolescent girls to boys respectively in Cameroon (37%: 30%), Ghana (21%: 5%), Mozambique (19%: 7%), South Africa (28%: 6%) and Tanzania (29%: 7%). These indications support the assertion that females are at greater risk of sexual abuse than their male counterparts [28].

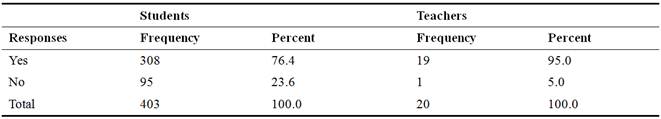

Table 2. Care Arrangement/Parental Absence, Substance Abuse and Parental Level of Education.

Table 2 shows another group of factors that are perceived to be responsible for sexual abuse of students in public senior high schools. From Table 2, respondents perceive that care arrangement/parental absence, substance abuse by parents and parental level of education are factors that facilitate sexual abuse in public senior high schools. Table 2 depicts that 308 students (76.4%) and 9 teachers (95%) of the respondents share the above perception. Meanwhile, 95 students (23.6%) and 1 teacher (5%) of the respondents do not agree with those factors. Large majority of the students (76.4%) and teachers (95%) perceive that care arrangement and parental absence could have serious negative implications for student development and protection while a parent with lower educational level may not be aware of suggested prevention programmes that will aid his/ her ward when it comes to sexual abuse.

These admissions are affirmed by a study conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa by [46] and [17]. According to the study, students who live with extended family, students who live in foster care, and students who live with just one parent face greater risk of sexual abuse than students who live with both biological parents. [28] go further to admit in a study conducted in South Africa that adolescents who were not living with a biological father reported an increased risk of teenage pregnancy in their schooling as a result of sexual abuse. Another perception of the respondents is the link between parental substance abuse and sexual abuse of students. This view is confirmed by one prospective study that suggested that students who had experienced sexual abuse often grew up in families where parents used drugs or alcohol [26]. In addition, a retrospective study that was conducted in Canada by [51] reported that respondents with sexual abuse increased by two-fold among those reporting parental substance abuse histories.

In the view of the researcher, the findings made imply that parental substance abuse may create an environment that is favourable for the perpetration of sexual abuse by incapacitating parents from giving the necessary monitoring and supervision. The opinion of the respondents suggests that there is a link that exists between parental level of education and sexual abuse of students. The admission is congruent with a finding made by [16] that mothers of those sexually abuse students are less likely to have finished high school.

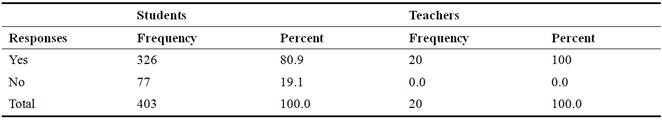

Table 3. School Environment.

Table 3 provides the descriptive statistical results of the admissions of respondents on school environment as a factor that promotes students sexual abuse in senior high schools. From Table 3, large majority of 326 students (80.9%) and 20 teachers (100%) of the respondents admitted that the school environment could be responsible for sexual abuse in high senior schools. Meanwhile 77 students (19.1%) are with opposite view. The admissions of students and teachers are confirmed by [45] who stated that student sexual abuse in school setting involves sexual favours in exchange for good grades as well as transactional sex where the victim is coerced into sexual activity in return for educational benefits such as school fees and material things.

Table 4. Demographic risk factor of Parents / Unemployment of Parents and Poverty.

Table 4. indicates that large majority of the respondents of 333 students (82.6%) and 19 teachers (95%) admitted that socio-demographic risk factors of parents could be responsible for the sexual abuse of students in public senior high schools. On other hand, 70 students (17.4%) and 1 teacher (5%) among the respondents holds different view against the admissions of the large majority of the participants.

According to the admissions of the majority of respondents, one of the factors responsible for sexual abuse in senior high schools is the socio-demographic risk factors of parents which include unemployment of parent and poverty level of parent. One can perceive from the Table 4 that unemployment is a risk factor for sexual abuse [26] argues that students who had experienced sexual abuse sometimes grew up with parents who were unemployed. [4] confirms the above assertion that unemployment may be a risk factor through stress of reduced material resources (i.e. resource dilution) a sense of powerlessness in the unemployed parent, who cannot afford the resources of their wards and their wards then seeking help from outside especially from their immediate environment.

The other side of the admission is that employment brings significant stress into the parent-student relationship and this has implications for studentscare arrangement. Perhaps, this argument could serve as a protective factor through a range of social-psychological benefits [42]. The finding of the study is inconsistent with a study conducted in Israel by [15] among female senior high school students. This study found that a higher occupational status of the parent was associated with higher likelihood of sexual abuse of student of those parents. This assertion in itself is puzzling. However, it is possible that daughters of such parents with high occupational status may actually experience higher rates of sexual abuse. If it happens, the cause could be the busy nature of the parents and poor child-parent relationship. The demanding nature of parentsoccupation could lead to disconnect with their wards thereby leading students to build trust in someone else in the school.

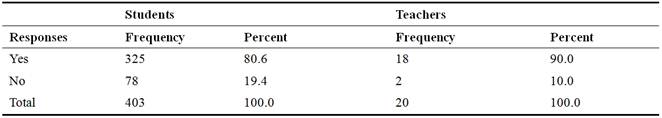

Table 5. Non- Nurturing environment and Poor Parent- Student Relationship.

Table 5 provides the results of the findings on non-nurturing environment as one of the factors that promote student sexual abuse in public senior high schools. From Table 5 students (80.6%) and 18 teachers (90%) of the respondents admitted that non-nurturing environment is one of reasons why students are sexually abused in senior high schools by perpetrators of the act. In the view of the researcher, a family characterized by absence of interpersonal attachment and good relationship may lead to bad supervision which in turn could result in insecure relationship with parents. [7] buttress this perception by arguing that families in considerable chaos and absence of personal connection could subject the students to emotional distress; students without this secure parental relationship may feel reluctant to disclose sexual abuse experiences to their parents or other adults, thereby perpetuating the act.

The respondents in the study hold a strong assertion that non-nurturing environment is a greater factor that makes sexual abuse conducive in the senior high schools. The perception is also confirmed by a study conducted by [2], it was noted in the study that insecure interpersonal attachment in a family may increase the risk of sexual abuse in that family. Alexander goes further to argue that if adult perpetrators of sexual abuse are not strongly attached to their students they may have poor control of their impulses and libido towards their students.

5. Conclusion

With regard to the factors that are responsible for student sexual abuse in public senior high schools, the following revelations were made: The majority of the students and teachers admitted that age and gender of the victims could be responsible for student sexual abuse. Care arrangement / Parental absence, substance abuse and parental level of education were revealed in the study to be some of the factors that a perpetrator of student sexual abuse in senior high schools may consider before undertaking their adventure on students. School environment is one of the main factors that respondents admitted that it promote student sexual abuse in public senior high schools. Demographic risk factor / unemployment of parents and poverty were admitted to be some of the factors that promote student sexual abuse in public senior high schools. Majority of the students and teachers are of the view that non nurturing environment and poor student- teacher relationship may cause student sexual abuse in public senior high schools.

It is recommended that Programmes aimed at alleviating household poverty in the districts should be extended to cover many more households. (i) There should be rapid implementation of the LEAP programme to cover households that are distressed to allow parents earn income and provide the basic needs of their children in order to protect vulnerable children from sexual abusers. (ii) Government should effectively implement school feeding programme to cover all deprived communities in the country.

Furthermore, the Ghana Education Service should be strengthening Institutions at District Level, in other words, Parents, community opinion leaders and institutions such as Police, District Assembly, Health workers, Teachers etc. identified as first point of contact when a student is sexually abused should be trained on how to identify and handle such forms of abuse cases. They should know cases that fall under their domain of work and those that should be referred to appropriate agencies to be addressed effectively. Institutions mandated to provide services to victims of student abuse, such as the District Assembly, Department of Social Welfare, Police Service, Health centres, schools etc. at the district and community levels should be facilitated and supported with the relevant material resources in prevention and handling of the cases.

References

- Adinkrah M. (2000). Maternal infanticides in Fiji. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24, 1543555.

- Alexander, P.C. (1992). Application of attachment theory to the study of sexual abuse. Journal Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 60(2), 185-195.

- Aniwa, M., Coker-Appiah, D., Cusack, K., Gadzkepo, A., & Prah, M. (1999). Breaking the silence and challenging the myth of violence against women and children in Ghana: Report of a National study on violence. Accra: Gender Studies & Human Rights Documentation Centre.

- Belsky, J. (1980). Etiology of child maltreatment. An ecological integration. American Psychologist. 35(4), 320-335.

- Birdthistle, L. J., Floyd, S., Machingura, A., Mudziwapasi, N., Gregson, S., & Glynn, J. R. (2009). From affected to infected orphanhood and HIV risk among female adolescents in urban Zimbabwe. AIDs. 22, 759-766.

- Black, D.A., Heyman, R.E., & Smith, S.A.M. (2001). Risk factors for child sexual abuse. Aggression and violent behaviour. 6(2-3), 203-229.

- Brown, J., Cohen, P., & Johnson, J.G (1998). A longitudinal analysis of risk factors for child maltreatment. Findings of a 17 year prospective study of officially recorded and self-reported child abuse and neglect. Child abuse and neglect. 22(11), 1065-1078.

- Brown, D., Riley, L., Butchart, A., Meddings, R., Kann, L., & Harvey, A. (2009). Exposure to physical and sexual violence and adverse health behaviour in African children: Results from the Global school- based student health survey. Bulletin of the World Health Organization.

- Buambo-Bamanga, S., Oyere-Moke, P., Genekoumou, A., Nkihouabouga, G., & Ekoundzola, J. (2005). Violences sexuelles A Brazzaville.Cahiers D扙tudes Et De Recherches Francophones, Sante Congo Brazzaville, Action Aid and UNICEF.

- Chaffin, M., Kelleher, K., & Hollenberg, J. (1996). Onset of physical abuse and neglect: psychology, substance abuse and social risk factors from prospective community data. Child abuse and neglect. 20(3), 191-203.

- Chege, F. N., & Sifuna, D. N. (2006). Girls and Women’s Education in Kenya: GenderPerspectives and Trends. Nairobi: UNESCO.

- Cole, J. (1995). Parental absence as risk factor in sexual exploitation of children. Act a criminological. 8,35-41.

- Cossins, A. (2000) 'Masculinities, Sexualities and Child Sexual Abuse', British Criminology Conference: Selected Proceedings. 3.

- Dubowitz, H. (1999). The families of neglected children. In M.E. Lamb (ED).Parenting and child development in non-traditional families. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Publisher.

- Elbedour, S., Abu-Badgers, A., Onwuegbuzie, A.J, Abu-Rabia, A., & El-Assam, A. (2006). The scope of sexual, physical and psychological abuse in a Bedouin-Arab community of female adolescents: The interplay of racism, urbanization, polygamy, family honour and the social marginalization of women. Child abuse and neglect. 30(3), 215-229.

- Finkelhor, D. (1994). Current information on the scope and nature of child sexual abuse. The Future of Children. 4, 31-53.

- Forster, G., & Williamson, J. (2002). A review of current literature of the impact of HIV/AIDs on children in Sub-Sahara Africa AIDs. 14 (3), 5275-5284.

- Gall, M. D., Gall, J. P., & Borg, W. R. (2007). Educational research: An introduction. Boston: Pearson Education.

- Ghana Education Service (2000). Conditions and scheme of service and the code of professional conduct for teachers. Accra: Ghana Education Service.

- Ghana Police Service (2008). Annual report: Domestic Violence Victims Support Unit, Ghana Police Service. Child Research and Resources Centre. Report on the study of child sexual abuse in schools. Accra: Plan Ghana.

- Goodyear-Brown, P. (2012). Handbook of child sexual abuse: identification, assessment and treatment. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley.

- Hampton, R.L, Senatore, V., & Gullota, T.P. (1998). Substance abuse, family violence and child welfare. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Higonnet, E. (2007). My heart is cut. Sexual violence by rebels and Pro-Government forces In Cote D抣voire. New York: Human Rights Watch.

- HM, Government. (2015). Working together to safeguard children: a guide to inter-agency working to safeguard and promote the welfare of children. London: Department for Education

- Holt, S. Buckley, H., & Whelan, S. (2008). The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people. A review of the literature. Child abuse and neglect. 32,797-810.

- Horwitz, A.V., Wisdom, C.S., McLaughlin, J., & White, H.R (2001).The impact of childhood abuse and neglect on adult mental health. A Prospective Study. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour. 42(2), 184-201.

- Human Rights Watch (2001). Scared at school. Sexual violence against girls in South Africa schools. New York: Human Rights Watch.

- Jewkes, R., Levin, J., Mbananga, N., & Bradshaw, D. (2002). Rape of girls in South Africa, Lancet, 359: 319-320.

- Jones (1996). An assessment approach to abuse allegations made through facilitated communication. Child abuse and neglect, 20, 103-110.

- Lacey, N.(1998). Unspeakable Subjects: Feminist Essays in Legal and Social Theory. Oxford: HartPublishing.

- Lalor, K. (2004). Child sexual abuse in Sub-Saharan Africa: A literature review, child abuse and neglect. World Health Organization, regional office, USAID. 286, 439-460.

- Leach, F., Fiscian, V., Kadzamira, E., Lemani, E. and Machakanja, P. (2003). An Investigative Study into the Abuse of Girls in African Schools. Education Research No. 56, London: DfID.

- Madu, S.N. (2002). The relationship between perceived parental physical availability and child sexual, physical and emotional abuse among high school students in the Northern Province, South Africa. The Social Science Journal. 39, 639-645.

- Nhundu, T. J., & Shumba, A. (2001). The nature and frequency of reported cases of teacher perpetrated child sexual abuse in rural primary schools in Zimbabwe. Child abuse and neglect. 25 (15), 17-37.

- Pinheiro, P. (2006). World report on violence against children. New York:United Nations.

- Pitche, P. (2005). Abuse sexuels D扙nfants Et infections sexuelles menttrasmissibles En Afrique Sub-saharienne.MedTrop. 65, 507-574.

- Plan International- Togo. (2006). Suffering to succeed? Violence and abuse in schools in Togo. Issued 4th November, 2006. Plan international. Retrieved: 20/08/2016. http://www.crin.org/docs/plan-ed-togo.

- Polonko, K., Naeem, N., Adams, N., & Adinolfi, A. (2010).Child sexual abuse in Africa and the Middle East. Prevalence and relationship to other forms of sexual violence.Paper presented at the 18th ISPCAN Congress. Honolulu, Hawaii-k。

- Reza, A., Breiding, M., Blanton, C., Mercy, J., Dahlberg, L., Anderson, M., & Bamrah, S. (2007).A national study on violence against children and young women in Swaziland. Swaziland: UNICEF.

- Richter, L., & Higson-Smith, C. (2004). The many kids of sexual abuse of young children. In Richter, L., Dawes, A., & Higson-Smith, C. (EDS).Sexual abuse of young children in South Africa. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

- Shakeshaft, C., & Cohan, A. (1995). Sexual abuse of students by school personnel. Phi Delta kappan. 76 (7), 512-520.

- Sidebotham, P., & Heron, J. (2006). Child maltreatment in the children of the nineties. A cohort study of risk factors. Child abuse and neglect, 30 (5), 497-522.

- Skinner, D., Tsheko, N., Mtero-Munyati, S., Seloabe, M., Chibatamoto, P., Mfecane, S., Chandiwana, B., Nkomo, N., Tlou, S., & Chitiyo, G. (2006). Towards a definition of orphaned and vulnerable children. AIDs and behaviour, 10 (6), 619-626.

- Stake, R. E. (2006). Multiple case study analysis. New York: Guilford press.

- Taylor, R., & Conrad, S. (2008). Break the silence. Prevent sexual exploitation and abuse in and around schools in Africa. Plan, West Africa.

- Thurman, T. R., Brown, L., Richter, L., Maharaja, P., & Magnani, R. (2006). Sexual risk behaviour among South Africa adolescents: Is orphan status a factor? AIDs Behaviour. 10,627-635.

- Together We Move South Africa Forward (2016) retrieved online on 20th August 20, 2016.http/twmsaf.com

- Turner, H.A., Finkelhor, D., & Ormstad, R. (2007). The effects of lifetime victimization on mental health of children and adolescent. Social Science and Medicine. 62,13-27.

- UNICEF - WCARCOD, (2006). Abuse, exploitation et violence sexuels des enfants al’ecole en Afrique de l’Quest et du centre. Dakar: UNICEF.

- UNICEF, (2008). Abus, Exploitation et violence sexuels a l‘encontre des enfants a l’ecole en Afrique de l’Ouest et du Centre. UNICEF Bureau Régional, Afrique de l’Ouest et du Centre.

- Walsh, C., MacMillan, H.L., & Jamieson (2003).The relationship between parental substance abuse and child maltreatment. Findings from the Ontario health supplement. Child abuse and neglect.27 (12):1409-1425.