To Human Language Origins

Wolodymyr H. Kozyrski1, *, Alexander V. Malovichko2

1The International Physical Encyclopedia Bureau, Mathematical Modeling Department of The Bogolubov Institute for Theoretical Physics, Kiev, Ukraine

2Physics Laboratory, The Lyceum at the National Technical University "KPI", Kiev, Ukraine

Abstract

We present a constructive synthetic approach to the problem of primary human language, its development, and its spread over the Earth. Comparative analysis of basic vocabulary in today languages supports the monogenesis hypothesis. We emphasize the importance of surprising extraordinarity of the Niger-Congo. Also, we give a collection of new nontrivial results and the model of global ethno-linguistic prehistory.

Keywords

Language Origin, Basic Vocabulary, Monogenesis, Comparativistics, Ethno-Linguistic Prehistory

Received: April 6, 2015 / Accepted: April 20, 2015 / Published online: May 11, 2015

@ 2015 The Authors. Published by American Institute of Science. This Open Access article is under the CC BY-NC license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

1. Introduction

Briefly identifying comparative linguistics, we say it is a comparison of the words’ value in different languages, from which you can make inferences explaining their origin, history, interaction, and so on. Of course, the words belong to some language group, language family and, finally, language phylum.

The main problem is that now there are over 7,000 languages involved in 11 language phylums. Studying so many languages is absolutely daunting task in practice. To alleviate these problems to anybody interested in, one should say that there are "major" and "non-principal" languages. Today "major" ones are English, Spanish, Russian, German, and so on. No one remembers Chinese. Such a division into major and non-principal languages is a tribute to the colonial past which most linguists can not get rid of from. Most linguists believe today that the first languages were Egyptian, Sumerian, Greek, Latin, and so on. Therefore, the modern linguistics is mainly not a science, but biased policy. As a result, linguistics has no progress.

In the paper, we expose our model of early language prehistoric stages containing fresh synthetic look at the problem.

The scope of the subject is restricted with the comparison of primary vocabularies contained in all the mankind language phylums.

The main goal of the paper, as we see it, is to present our synthetic model of early language prehistoric stages.

The novelty of research work lies in its grounds combining known and newly established by the authors linguistic facts with large amount of excitive research data from related disciplines such as archaeology, paleoanthropology, and modern genetics.

We organized the paper as follows. At first, we outline certain features stimulating the problem research. Then, we expose our Analytic Investigation of all the facts we established up to now that gives us non-trivial results. We discuss them in what follows and end the paper by Summary and Conclusions, and References.

2. Research Significance

In view of this, it is not clear why most scholars can not imagine that a human and his language appeared at the same time. Something more stricter, archanthropines becomes a human starting to use a language. Experts believe that a human appeared 2 million years ago and, however, learned to talk very late just in a few hundred millennia. It turns out that human was dumb for enormous time. It is impossible to imagine all beings communicating with each other, but an unhappy human can not speak and modestly silent. Our synthetic model lays the foundation for the ethno-linguistic prehistory.

History of Linguistics contains scenes that a reasonable man does not understand at all. In 1991, Merritt Ruhlen in the paper "The Origin of Language: Retrospective and Perspective" recalled that "any discussion on the origin of language was banned by the Paris Linguistic Society in 1866" [1]. Taboo shows that the Paris Society did not understand the problem as it was. And, at last, what a science is it that can be forbidden.

At a certain stage of development, linguistics lost its perspective at all. One reason for the crisis is non-understanding of its development by the top legislators (the Moscow school). The second reason is the total lack of understanding of the time of human appearance and his ability to articulate speech.

At the end of the nineteenth century, some linguists have disobeyed Paris Society and continued linguistic studies, whereby linguistics emerged from the stagnation.

The next stage of linguistic crisis occurred with the beginning of active development of Indo-Europeistic studies. However, even today, a whole army of Indo-Europeists cannot determine when and where these languages could appear. One can find a large number of hypotheses about the origin of the Indo-European territories and their languages in S.A. Burlak and S.A. Starostin [2].

3. Analytic Investigation

We consider the situation where different archanthropines species lived side by side and may have different languages that gradually disappeared except for one kind or another. It is clear that languages at the stage of primary development were very primitive ones. In this case, one has to use the conditions we specified in [3], namely, the main feature of the appearance and development of language is the way from simple to complex. We believe it is a quite natural feature of establishing anything new.

Unfortunately, leading linguists do not support this thesis. It seems they have their own special conditions. In the situation described, we can build a model of the appearance of the first language in Africa being the home of all languages. Why in Africa alone, and not in some other place? Our answer is simple: a language occurred at the place where a human first appeared. We believe it is an area in the Great Rift Valley of East Equatorial Africa.

In addition, already 2 million years ago a Human had mastered some vocabulary that we named "primary." It was supposed to ensure normal conditions of human existence. The "primary" list should include the first human words and, of course, the sequence of occurrence of these first words.

If one relies upon the hypothesis that there was a unique language of the Earth of yore, then any language must contain the same "primary" vocabulary. That is, the "primary" human vocabulary contains the words 'water', 'fire', 'eye', 'sun', 'fish', 'grab', 'cut', 'eat', 'child', 'I' 'stone', 'to know', 'many', 'big', 'two', 'talk', 'meat', 'belly', 'large' ('long'), 'turtle', 'salt', 'beat', and so on. On this basis, we formulate the main requirements for the "primary" vocabulary:

1) It should be very simple, that is, composed of two sounds (in the extreme case, three), that is, the vowel + consonant sounds, or vice versa, consonant + vowel sounds;

2) The number of "primary" words should not exceed 2–3 dozen (probably together with the names of wild animals).

3) "Primary" vocabulary is unique, absolutely original in comparisong with any other vocabulary because it is in all the languages of the Earth (original because it was "primary" one). One has learned that "primary" vocabulary does not depend on what language we consider, therefore it is a universal one.

Up to now we do not saying that the forms of the vocabulary in different languages, of course, are different ones. The forms of vocabulary are what we say. See more below.

Despite the fact that linguistics is "safely" existed for 220 years, up to now there is no fundamental textbook of this science. Although many people will be outraged by such an approach, in our opinion, these challenges require a new approach.

Can one do the actual linguistics with a monograph "Indo-European Language and the Indo-Europeans" by Gamkrelidze and Ivanov? It has neither beginning nor end. [4] Having written "Comparative and Historical Linguistics", 2005 [2], and calling it a "textbook", Burlak and Starostin decided that the manual allows to extend its principles to the remaining 10 language phylums without prejudice to the very linguistics. However, in their textbook authors have limited themselves by only Indo-European linguistics.

In the Appendix, the authors proposed "Genetic Classification for Languages of the World" in 11 phylums: 1) Nostratic, 2) Afro-Asiatic (Semito-Hamitic languages), 3) Sino-Caucasian (Dene-Caucasian languages), 4) the Chukchi-Kamchatka, 5) Austric 6) Amerind, 7) Australian, 8) Khoisan (Bushman-Hottentot languages), 9) Nilo-Saharan, 10) Congo-Kordofanian, 11) Indo-Pacific. 5 phylums of these 11 phylums are in Africa.

Joseph Greenberg in his book "The Languages of Africa " [5] writes that there are 6 languages phylums in Africa. This inconsistency has its consequences. We think we can first confine ourselves with five phylums: Niger-Congo, Nostratic, Khoisan, Nilo-Saharan, Kordofanian. Last phylum is almost identical to the first one. The authors of the textbook [2] forgot the main phylum, Niger-Congo one. It is known that Nostratic phylum includes also Semito-Hamitic languages [6].

The neglect of any language other than Indo-European (I-E) one was approved by Gamkrelidze and Ivanov monograph [4]. The book was neither a textbook nor handbook in linguistics. Therefore, Burlak and Starostin book met all the requirements for this type of books. However, in the chapter 1.8 of this book "Microcomparativistics" (p. 108), the authors write: "...In the literature 8 – 10 thousand years often appear as an absolute limit for the possibility of establishing linguistic affinity ... although usually one does not say where the figure is taken of. In fact, it goes back to the standard glottochronological formula by M. Swadesh, according to which during 10 000 years two related languages preserved only 5–6% of the total vocabulary, i.e., a situation in which a direct comparison of languages can not give positive results and it is impossible to distinguish between native related morpheme and random coincidences (in case of deviations of the order of 16 000 years, according to the Swadesh formula, languages in general should lose everything similarity)." And further: "This simple idea is the basis of all criticism of existing theories of far linguistic affinity." So, comparativistics in the sense of Indo-Europeists becomes completely meaningless. And these experts have nothing to say "something useful" on "deeper" history. Also, they say that the history of languages (ie, all languages) is limited to thirty or even twenty thousand years.

If we take the model of global vocabulary of the mankind with the continuity of the evolutionary chain of language vocabulary from "primary" language of Homo erectus to languages of both Americas, then we can reconstruct such a chain. A similar idea was proposed by S. Starostin [7] and, before him, by Alfredo Trombetti [8].

Previous quotes apply only to the Indo-European languages. And if one investigates not only the Indo-European languages? In that case, one should probably offer some way out of this complicated situation.

A.N. Barulin [9] wrote about this stalemate much better. The author recognized that "... there are three logical possibilities: the language arose before the Cro-Magnon, the language emerged simultaneously with the Cro-Magnon, and language originated later than the Cro-Magnons appeared. There are many supporters of the first hypothesis among biologists, anthropologists, linguists, and philosophers. Although I must say that the arguments in favor of a decision still lacks scientific foundation." And further: "In the above quotations, authors of linguistic works also come from the view that it originated or until the Cro-Magnons, or about the time of their development as a species. There are no serious arguments."

Thus, the Indo-Europeists left without prospects wasting two centuries for full of nonsense. It is doubtful that one can create a history of the language without the involvement of the results of other historical disciplines, especially paleoarhaeology, paleogenetics, and paleoanthropology. We involve them into our considerations.

To cover the whole human development, one must know the current views of paleoarhaeologists that are most fully reflected in [10]: "The most ancient sites of human with stone tools... are deployed mainly in East Africa in the area of the East African Rift, trailing in the meridional direction from the depression of the Dead Sea through the Red Sea and beyond the territory of Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania. In the basin of the river Kada Gona on the location on the surface and in the layer there were detected more than 3 thousand artifacts. Stone tools recovered from the layer below the tuff, whose age is 2.5 million years." And further: "About 2-1,8 million years ago Homo ergaster-erectus left his "cradle" and moved out of Africa, which gave rise to the first Great Migration, an event marked the greatest importance, the settlement of the world by human beings."

Fig. 1 contains a "biography" of ancient hominids from ancient ape-men and the advent of Homo ergaster-erectus and ending our time. It seems that all in this picture is clear. However, we have no explanation for the part of this schedule from the time of Homo ergaster separation from Homo erectus to our time. The figure shows that this species lived, not changing, the last 2 million years. And they were talking, most likely, in a language that they "invented" 2 million years ago and survived to this day. We can therefore assume and assert that just this primitive language was used by the people who lived in Africa, which eventually went to live in Eurasia, and later in the Americas.

According to A. P. Derevianko, the first thread moved through Central Asia, Kazakhstan, Altai, and came finally to Mongolia: "About 450 – 350 thousand years ago, the second migration flow began to move from the Middle East to Eurasia... In many areas, the new human population met representatives of the first migration wave and their two industries, pebble and late Acheulian, have mixed." Thus, above-described Homo ergaster-erectus "biography" needs some explanation. Firstly, most of the authors, describing archanthropines’ groups propagation, write as if the group leaving some territory left nothing behind it. They did not leave even their language, as if moving to a new area they forgot their previous language. That is, one would think that Homo erectus leaving Africa left no body behind him.

Fig. 1. [11]. Hominid evolutionary tree

In fact, Homo erectus had settled Africa for a very long time (outside Africa too). That is, until a new population emerged which also seems to be originated in the interior of Africa not later than 500 thousand years ago, Homo erectus language was remained the same as was "invented" by early Homo ergaster-erectuses.

Thus, according to Fig. 1, starting with 2 million years ago (and probably later), Homo ergaster-erectus had divided into two streams: Homo ergaster and Homo erectus. Paranthropus species ceased to exist by the beginning of the second million years ago leaving no descendants. As can be seen, the Homo ergaster graph begins with the separation of the original stream into two. It was about 1.8 million years ago.

The articles on this issue have nothing about the areas settled by Homo erectus at that time. No one ever said on his fate. We never had the possibility to know anything about the final stage of Homo erectus species life. Of course, this is of great importance to our construction, hinting at a very late extinction of Homo erectus. In our opinion, this species has not disappeared, but likely lived up to this day.

How far to the east he settled the South Asia and how long it took him to this promotion, is difficult to say. Homo erectus settled Pakistan, India, southern China. According to archaeologists, human has occupied these vast areas no later than 1 million years ago. Derevianko writes: "North migration wave of ancient human populations through Near East entered Iran and then to the Caucasus and possibly Asia Minor. Convincing evidence of this settlement is Dmanisi location (East Georgia) being one of the most outstanding in Eurasia [12,13]." And further: "One thing is certain: human took about a million years to gradually populate the vast expanses from Africa to the Pacific and Indian Ocean. However, the whole history and development of human culture took place in the same species environment, namely, among Homo erectuses"[10].

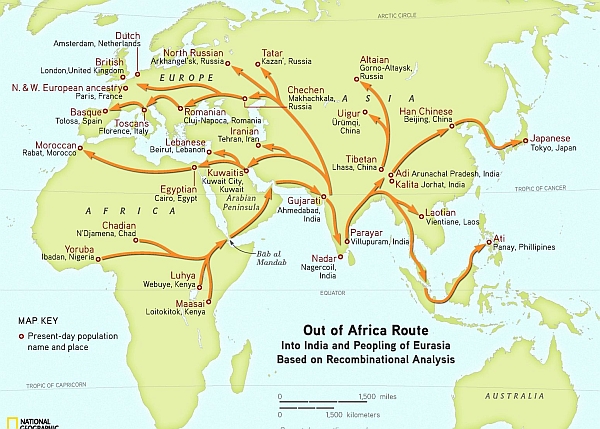

Returning to the quote "About 450–350 thousand years ago, the second migration flow began to move from the Middle East to Eurasia... In many areas the new human population met representatives of the first migration wave and their two industries have mixed...", we must say that the opinion of archaeologists and linguists that the first human appeared in the Middle East is a misconception. Therefore, archaeologists have to explain relations between first and second migration flows. As for the arguments of linguists, we must remember that the Nostratic languages include Cushitic and Chadian. These were the first Nostratic languages, that is, the earliest, whose homeland is very far from the Middle East in the heart of Africa. Based on these data, we propose a model of the origin of these languages. The overriding in our model is that the earliest phylum on the African continent was Niger-Congo language family. The Map of IBM Corporation Genographic Project <www.nationalgenografic.com> [14] confirms our model. Genographic Project published in 2011.

Now, about the forms of "primary" language. Joseph Greenberg [5] wrote on them, considering that in Africa 6 language phylums carriers lived (and live up to our time), only one of which may be the oldest, unless, of course, based on the hypothesis that only one language was in the world. The essence of the hypothesis, in our opinion, is that the language was invented by, relatively speaking, "first couple", whose heirs have survived to our time. Probably the "first couple" could really exist. Otherwise, you'll have to invent some other model of the emergence and spread of man over the Earth.

From the beginning, Joseph Greenberg decided that the ancient language was one of Afroasiatic. It was the main J. Greenberg argument. This language began to spread over Africa and later throughout the world. However, we are faced with another problem that J. Greenberg could not handle. The question is, where there was a specific territory homeland of Afroasiatic languages. Of course, the answer may be twofold. First answer is Africa. The second one is the Near East.

Fig. 2. Map of routes out of Africa

Of course, the first answer is the correct one because otherwise the beginning of mankind would have to be sought not Africa, but Near East.

Today routes of the earliest people spread are known. The Genographic Project Map (Fig 2) shows two routes starting in the first place in Equatorial East Africa (to be precise, in the Great Rift Valley). The second route of migration began with the Central and West Africa. The difference between the two routes is that the first route appeared "immediately" after the hominid species Homo ergaster-erectus occurred, that is, two million years ago. And the second was formed only in 1.5 million years after the first one. African parts of both routes end at the Strait of Bab el Mandeb.

As we noted above, on the map there are two sources (more correctly, four) of this hominid species' appearance. One is an area marked on the Map by the name Luhya (Webuye, Kenya) and Maasai (Loitokitok, Kenya). And the second source is in West Africa at the territory of Yoruba (Ibadan, Nigeria) and Chadian (N’Djamena, Chad) language speakers. Analyzing the Map, you would think that both sources were moved to the side of the Strait of Bab el Mandeb. And another error: allegedly Homo erectus descendants vocabulary was different. In fact, in our opinion, the language sources were such ones: West African languages were a continuation of "primary" Niger-Congo language vocabulary. Table 1 helps to ensure this.

For almost one and a half million years, as we have noted, Homo erectus spread westward. During this time he added a new language vocabulary (in addition to the original vocabulary of Homo erectus). In Table 1, we can see an example of replenishing language spoken in West Africa as a supplement to the "primary" Niger-Congo language vocabulary. The same thing happened with the Nostratic languages vocabulary, which were replenished with Cushitic and Chadic languages vocabulary. But the main difference between these migration flows is that the first thread started 2 million years ago, and the second one only 450–350 thousand years ago. That is, the second thread appeared one and a half a million years later.

One can assume that the vocabulary of the carriers of these streams is different. However, the vocabulary of the second stream is a development of the first language. We demonstrate this in Table 1. This is our main conclusion.

As of the appearance of man: after the hominid species Homo ergaster-erectus occurred in Equatorial East Africa (very early, that, generally speaking, it is not a common thing), they have for nearly a million (and maybe more) years continued spread over Africa, including the Northwest Territories and, of course, beyond. We do not think that erectuses can penetrate the virgin forests of the Congo Basin. Rather, they prefer savanna. Therefore, they had settled on the lands of the East African Rift Valley, from which came to the sea.

After that, and later they probably settled in Central and West Africa. This direction is drawn on the Map. It is therefore clear that Homo erectus left Africa through the Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb.

The same we can show returning to Figure 1. Approximately 2 million years ago Homo ergaster-erectus occurred that was a descendant of the previous two species Homo rudolfensis and Homo habilis. Later Homo ergaster-erectus divided into two parts, one of which lived independently (Homo erectus) before reaching our days. The second part, Homo heidelbergensis, later became Homo sapiens.

Therefore, we explain the change of the Niger-Congo languages vocabulary to Nostratic (including Cushitic and Chadian) ones as parts of the Afro-Asiatic (Sem.-Ham.) languages by the fact that Homo erectus language was, as we think, the language of the African Niger-Congo family travelled to the west with its carriers. Naturally, it had enriched with new vocabulary in the new life conditions at the today Cushitic and Chadian tribes’ areas.

4. Discussion of Results

We already have the latest information confirming said above. Take a look at Table showing the primary language vocabulary Niger-Congo with the vocabulary of the Afro-Asiatic family of Nostratic phylum. Illich-Svitych Dictionary was created before the death of the author [6] in Moscow in 1966. We believe, Table 1 contains a number of primary dictionary words that have the same roots.

In Table 1: Alt. – Altaic, S.-H. – Afroasiatic, Kart. – Kartvelian. Alt. include: Turk. – Turkic, TM – Tungus, Mong. – Mongolian, Kor. – Korean, Jap. – Japanese. St. – Vocabulary from Starostin [15] Altaic book. Amerind – Amerind languages of the Americas from Greenberg and Ruhlen [16]. (SSO) means "Kartvelian vocabulary" by Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani (in Georgian, XVIII century) [17].

5. Summary and Conclusion

If we found a few words in modern bilingual dictionaries of African, it could get quite full Table of primary vocabulary. However, up to now there are no such dictionaries for the most of the world languages. Therefore, our Table has gaps sometimes filled with random sources.

Having combined these graphs and tables, we obtain a universal table whose content begins in Africa and ends in America. In such a way, we will restore the chain from the oldest Niger-Congo phylum in Africa through the Semito-Hamitic Afro-Asiatic languages of Central Africa (first of all Cushitic and Chadian languages, Nostratic in origin), and then through the languages that are now outside of Africa. So far we have dealt only with the Kartvelian and Altai vocabulary. Further movement over Eurasia took place to the east, while Homo erectuses with their language settled all the America about 50,000 years ago.

Using our table, we can say with a high probability that the carriers of Kartvelian languages very early occupied the land of the South Caucasus. We have in mind early hominids found by paleoarhaeologists at Dmanisi location [8]. These problems constitute the second part of our research. In addition, having in our Table the Nostratic vocabulary and Altai vocabulary within it, we suppose that the inhabitants of the Denisovan cave could speak Altai languages. Especially that the inhabitants of this cave occurred not before (rather later) than 400 thousand years ago.

The reader interested in the problems discussed in the paper can also see the results of authors’ preliminary eightfold-way axiomatic model published in [18].

Table 1. Basic vocabulary comparison

| N | Word | Language phylum | ||

| Niger-Congo | Nostratic | Amerind | ||

| 1 | water | Looma zi, zie, zia | Alt.St*suwV(tat. sɨw) Kart. sweli, sueli – ‘wet’ | 856 *si, 863 c’i |

| 2 | fire | Swahili moto, ot, woti | Il-Sv343 *qot’i –‘burn’, ‘fire’ S.-H. ḫt’-/ḫt’‘burn’, ‘inflame’ West.Cush.*Ht Wolamo ētt; Gimirra ot –‘boil’, ‘bake’; Kaffa att(i) ‘burn’; Mocha ᵓàt’t’a – ‘inflame’ Alt. St. 81*ot’V: Turk. *ōt, anc. Turk *ōt | 272 *(?)oti |

| 3 | eye | Susala ni, Mossi ni(fu) Susu nia, Dan nya, Nafana nie(ne) | Alt. St. 21*ńiā: ТМ ńiā-sa | 251 *nak Nivkh: eye – niakh |

| 4 | cut | Bwamu ta, Kpelle,Nyangbo, Bassa, Guand, Mbuam te, Zande de Niger Saharan Dinka, Nandi tem | 168 *t’an, 170 *t’ek’ | |

| 5 | know | Proto Bantu *manya – ‘know’, Ibo ma, Mbum ma – ‘think’, ‘mind’, ‘understand’ | Il-Sv 281 *manu – ‘think’ S.-H. mn ‘think’, ‘understand’, ‘want’ East. Cush. Somali mān – ‘mind’ West. Chad ‘know’, ‘understand’: Bolewa mon, Angas, Ankwe, Montol, Sura man, Masa min – ‘want’ | 423 *ma(k) ~ ma(n) |

| 6 | child | Hoke ba, Proto Bantu biad, Gbaya be, Mossi bi, Bariba bii | Il-Sv 32 *b/\r/\ S.-H.bir;Cush Sakho bār’a, bāl’ā,Afar– bāl’ā – ‘child’, Darasa belti ‘son’, belto ‘daughter’;St314*bāldV Turk. bälä, TM *baldi - ‘give birth’ Kart. Bere | 128 *pan, 131 *pam |

| 7 | fish | Looma (arch.) – kalа | Il-Sv 155 *kal/\: S.-H.: East Cush.*klm; Somali kállūn, kellūn. Chad. *klph – ‘fish’; West Chad.: Hausa kifi, Bura kӛlfa Аlt. St362 *k’olV: ТМ *xol-sa – ‘fish’ Kart. kalmaxi – trout | 289 *k’al ~ kal |

| 8 | many | Looma moin, moin | St. Alt.45*mānV:Kor.*mān(h) Jap. *mania | 475 *moni |

| 9 | speak | Proto Bantu ti,Awuna, Adele, Ewa te – ‘tell’, Bini, Efik te, Bini ta | Alt.St202*tē – ‘say’,Turk.*dē anc. Turk., Chuvash. te; Kart. titini – (SSO – ‘chatter’) | 618 *ti |

| 10 | two | Messo bala, Nalu bele, Nimbari bola | 821 *(ne)pale | |

| 11 | stone | Kasele, Adele (de)ta, Bua, Gbaia ta, Kam tal, Kamuku tale | Alt. St68 *tiola (Turk. *dal) Kart. t’ali –‘flint’ | 721 *tak |

| 12 | seize | Swahili kamata | Il-Sv190*k’aba/kap’a Alt. St 318 *k’ap’V–‘catch’,‘keep’,Turk.*kap TM*xapki, Kart. k’b –‘bite’ SSO xapangi – ‘trap’ | 137 *q'ap(a) – close |

| 13 | big | Looma bala, bolo | Il-Sv350*wol(a) S.-H.Cush.Bedja w:u/i/ē:n; Somali wejn; Chad. Angas warn, Sura wúráη, Bura walaka, Margi ᵓwál, Musgu wēl; old Slav. Velьmy – ‘very’, ‘too’ | 62 *pala |

| 14 | big (long) | Warwar Mambila da – be long, Proto-Bantu *dai, Niang dada ‘be long’, ‘high’, Mbum, Banda di, Ewe didi | Il-Sv66*did/\ – ‘big’ S.-H. d(j)d ‘big’, ‘thick’; Chad. Gider dide – ‘big’; Kart. did – ‘big’ | 427 *ta(k) – ‘big’, ‘large’ |

| 15 | belly | Kissi puli, Mossi pu(ga) Dagomba puri, Proto-Bantu *pu, Barambo bulu, Mumuye buru | St.3 *päjlV–‘belly’ Turk. bēl. Mong. feligen, Kor. păi, Jap. pàrá | 57 *pal(i) |

| 16 | fall | Nzakara, Zande ti, Gbanziri ti, Bwaka, Mba, Banda te | 255 *tik | |

| 17 | tortoise | Proto Bantu*kudu, Susu kure, Bozo(Soninke) kuη | Kart. ku | 820 *kuli (turtle) |

| The next examples are not so evident. However, we included them into the Table | ||||

| 18 | carp/fish | Swahili karapu Amhar. karp | Kart. k’orbu, Ital. carpa, Eng. carp Ukr. k’arp, Chech. karp | Tagal. karpa, Nivkh. karp |

| 19 | goose (2-nd stable name is Bat-i ) | Swahili batabukuni – goose, bati – duck | Kart. bati – goose | Miwok duck – watmal |

References

- Ruhlen, M. The origin of languages: retrospect and prospect. In: Problems of linguistics, № 1. Moscow. 1991. (Russian translation).

- Burlak, S.A., Starostin, S.A. Comparative and Historical Linguistics. Moscow, 2005. (In Russian).

- Kozyrski, W.H., Malovichko, A.V. Could prehistoric hunter language be retained?( Language nonogenesis III). Origin of language and culture: ancient history of mankind, 1, № 4, 18–24, Kiev, 2007. (In Russian).

- Gamkrelidze, T.V., Ivanov, V.V. Indo-European Language and Indo-Europeans. Tbilisi, Georgia. 1984. (In Russian).

- Greenberg, J. H. The Languages of Africa. Bloomington, Indiana. 1963.

- Illich-Svitych, V.M. Experience of Nostratic Languages Comparison.V.1. Moscow, 1971; V.2. Moscow, 1976; V.3. Moscow, 1984. (In Russian).

- Starostin, S.A. Interview to the Journal "Knowledge itself is Power", № 8, 2003. (In Russian).

- Trombetti, Alfredo. L’unita d’origine del linguaggio. Bologna, 1905.

- Barulin, A.N. Glottogonic theory and comparative-historical linguistics. (In Russian)<www.dialog-21ru/Archive/2004/Barulin.htm>.

- Derevianko, A.P. The early human migrations in Eurasia and the problem of forming Upper Paleolithic. Archaeology, Ethnology, and Anthropology of Eurasia, 2(22), 22–36, 2005. (In Russian).

- Hominid evolutionary tree ( Smithsonian Institution).

- Dzaparidze, V., Bosinski G., et al. Der altpaläolithische Fundplatz Dminisi in Georgian (Kavkasus) // Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen-Zentralmuseums, 1991, 36, 67 – 116.

- Gabunia, L., Vukua, A., Lordkipanidze, D. New finds of bone remains of fossil man in Dmanisi (Eastern Georgia)// Archaeology, Ethnology, and Anthropology of Eurasia, № 2 (6), 128–139, 2001. (In Russian).

- IBM Corporation Genographic Project: <www.nationalgenografic.com>.

- Starostin, S.A. Altaic Problem and the Origin of the Japanese Language. Moscow, 1991. (In Russian).

- Greenberg, J. H., Ruhlen, M. An Amerind Etymological Dictionary. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. 2007.

- Orbeliani, S.-S. Georgian Lexicon. Tbilisi, Georgia, 1928. (Russian translation from Georgian).

- Kozyrski, W.H., Malovichko, A.V. Language Prehistory. Kiev: The Steel Publishing. 2012.