An Ethnographic Investigation on Land and Life of Santal Community in Barind Tract, Bangladesh

Mashiur Rahman Akan1, Md Abdullah Al Mamun2, *, Tahmina Naznin1, Muha Abdullah Al Pavel3, 4, Lubna Yasmin2, Syed Ajijur Rahman5, 6, 7

1Department of Anthropology, Faculty of Social Scinece, University of Rajshahi, Rajshahi, Bangladesh

2Department of Folklore, Faculty of Social Scinece, University of Rajshahi, Rajshahi, Bangladesh

3Water Resources Development, Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology, Dhaka, Bangladesh

4Department of Forestry and Environmental Science, Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Sylhet, Bangladesh

5Department of Food and Resource Economics, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

6School of Environment, Natural Resources and Geography, Bangor University, Bangor, UK

7Center for International Forestry Research, Bogor, Indonesia

Abstract

This paper is an investigation of life style of Santal community, one of the largest tribal communities in Bangladesh. Participatory rural appraisal (PRA), participant observation, focus group discussions (FGD), and informal and semi-structured interviews were used to collect information. Santals are the descendants of Austric-speaking Proto-Australoid race, and worship the supernatural powers. Village as a territorial unit, a collection of some homesteads form an administrative unit where they also tightly bond to a kinship. Even they are very sincere in abiding the rules and regulations of their own society, social problems i.e., poverty, inequality, resource scarcity, illiteracy, maladjustment are more severe. Respecting the national constitution, Bangladesh should generate a multi-ethnic leadership to bring glory and protect Santal from all sorts of hazards and discriminations.

Keywords

Ethnic Minority, Lifestyle, Institutions, Inequality, Woman

Received: April 1, 2015

Accepted: April 12, 2015

Published online: May 22, 2015

@ 2015 The Authors. Published by American Institute of Science. This Open Access article is under the CC BY-NC license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

1. Introduction

Bangladesh is one of the most remarkable cross-cultural countries in South Asia. With the respectable number of rivers, the land of this country is very fertile and consequently many ethnic people came to live here. These people are very much respectful to their unique values, culture, beliefs, rituals and practices. Geographically, these ethnic people live in the different regions i.e., Sylhet, Mymensingh, Chittagong Hill tracts, and North-west region (Karim, 2000; Hussain, 2000). The living style of the ethnic people is changing day by day due to rapid deforestation and various socio-economic aspects e.g., free trade, globalization. The Santal is an ethnic group in Bangladesh, mainly living near the Himalayan sub-mountain region of Rajshahi Division. Their orgin is in India i.e., Radha (West Bengal), Bihar, Orissa, and Chhotanagpur. According to the most recent estimate, the total number of the Santal population in Bangladesh is two hundred thousand (Minority Rights Group International, 2008). Santals are the descendants of Austric-speaking Proto-Australoid race. Their complexion is dark, height medium, hair dark, heavy lips and they are similar to other clan of the indigenous people of Bangladesh i.e., Mundari, Oraoum and Paharias (BMDA, 1999). They believe Thakurji as the creator and a son is immortal, and the supernatural soul determines worldly good and evil. Bonga occupies an important place in their daily worship, that is why the house-deity Abe-Bonga is quite a mighty God. The influence of Hindu deities is also visible in their religious ceremonies. They are festival loving and have thirteen festivals in twelve months celebrated with dance, songs, music and pleasant beauty of flowers. The Santal is mainly matriarchal and poverty is their constant companion. Women usually wear colorful saries and men wear Dhutis and Gamchhas (short cloth). They are beauty conscious and have tattoos on their bodies. Rice and vegetables are their staple food (Banglapedia, 2003). Santal is derived from Soontar and according to the anthropologists they are the progenitors of Santals (Karim, 2000; Hussain, 2000). Some Bengali scholars have the opinion that the name of Santal has been derived from Samantalpal, a place of West Bengal, India where Santals used to live in a large number. But true to their nomenclature, they like to be locally known as Kherwal or Kherwarh. Nevertheless, this name is less known they have regardless accepted the name Santal (Sattar, 1983). The Santal supports their livelihoods with traditional methods of hunting, fishing and cultivation, but not vividly documented in the scientific literature. Therefore the purpose of this paper is to investigate the lifestyle of the Santal community in the Barind Tract of Bangladesh.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

Godagari Upazilla (sub-district) in the Barind tracts of Rajshahi district, Northern Bangladesh has been selected as a study site, because a good number of Santal people are living in this area. The total area of Godagari Upazila is 472.13 sq km, located in between 24°21´N to 24°36´N latitudes and 88 17´E to 88 33´E longitudes (Banglapedia, 2012) (Figure 1). However, Barind Tract is the largest Pleistocene photographic unit of the Bengal basin, covering an area of about 7,770 sq km. It has long been recognised as a unit of old alluvium, which differs from the surrounding floodplains. Geographically, this unit lies roughly between latitudes 24 20´N to 25 35´N and longitudes 88 20´E to 89 30´E. The Barind Tract covers most parts of the greater Dinajpur, Rangpur, Pabna, Rajshahi, Bogra, Joypurhat and Naogaon districts of Rajshahi division (GOB, 2010; Banglapedia, 2012). Barind tract is rich in vegetation, as it abounds in varieties of bamboos, date palms, mango groves and other trees e.g., Acacia nilotica, Azadirachta indica, Shorea robusta. Most of the villagers' rear cows, bullocks, goats, pigs, dogs and poultries e.g., hen, goose. Paddy is the main crop of this region. Now a days highly yielding rice variety (IRRI) is widely cultivated in the Barind tract. But, different types of paddy i.e., Pariza, Shorna are also grown all the year round. This has been made possible by the application of modern irrigation technologies.

2.2. Methods

The primary data were collected by (1) participatory rural appraisal (PRA), (2) participant observation, (3) focus group discussions (FGD) (3) informal and semi-structured interviews. We have employed two key informants to gather reliable data from the study site, and to gather more insight about the local culture and beliefs. The household heads provided household information and in case of their absence the senior and /or responsible adult members have replaced them. Secondary data have been collected from local administrations, relevant documents, journals and reports. The data collected by interviews were cross- checked with key informants and people of diverse strata of the society. At the stage of data analysis, qualitative and semi-quantitative analysis methods were carried out.

Figure 1. Study area (highlighted in red) [Source: 2015 AutoNavi, Google]

3. Results and Discussion

In order to get a comprehensive idea of the structure of a society, it is important to discuss from the level of the individuals, since the individual is the basic unit of a society. Each and every individual is unique in character and differ from one another. This distinction is generally determined by age, sex, material status, religion, occupation and ethnic identity. In spite of these differences, each individual depends on the other in his daily life and other social functions that constitutes a network of relationship among themselves. On the other hand, every individual is associated with the different institutions in society maintaining their status and roles. Social organization is an aspect of social system, which denotes the systematic ordering of social relations through acts of choice and decision. These actions are limited by the range of possible alternatives. This observable behavior, including change and variation in a social system is accounted for its social organization. Some important factors e.g., marriage, belief, income are obviously liable to maintain the social relations among individuals and groups. With a view to maintaining socially determined norms, values and other rules, these factors can by no means be ignored.

As an institution, marriage is a socially recognised and approved union between individuals, who commit to one another with the expectation of a stable and lasting intimate relationship. It begins with a ceremony known as a wedding, which formally unites the marriage partners. A marital relationship usually involves some kind of contract, either written or specified by tradition, which defines the partners’ rights and obligations to each other, to any children they may have, and to their relatives. In most contemporary industrialised societies the government certifies marriage. Marriage is a part in the life-cycle of a man vis-à-vis the human society. In generic Santal term for marriage is bapla. In addition to being a personal relationship between two people, marriage is one of society’s most important and basic institutions. Marriage and family serve as a tool, ensuring social safety, providing food, clothing, and shelter for family members; raising and socializing children; and caring for the sick and elderly.

In families and societies in which wealth, property, or a hereditary title is to be passed from one generation to the next, inheritance and the production of legitimate heirs is a prime concern in marriage. In fact, marriage is commonly defined as a partnership between two members of opposite sex known as husband and wife. In most cases a woman who marries moves to her husband’s home from her own home. Senior males (and their wives) exercise power in the family. Disputes within the family, which can be common, may result in partitioning of land or even of the house compound. The Santal consider marriage as essential for every adult, and old bachelors are particularly unknown among the Santal community (Roy, 1928).

The most important institutions of the social structure are the family, its types and authoritative system. In rural Bangladesh as well as in the study village, the family is a domestic group, which provides the most intimate needs of its members, a realm of privacy familiarity and security. The family is primarily responsible not only the dependent young, but also to the care of its aged members and for any of its members sufferings from illness, accident or misfortune. Most of the village people live in a nuclear family. But in tradition, it is claimed that the people of the rural area of Bangladesh live in joint family. But in this study, it is found that most of the families have nuclear family structure (67%) and those have belong to joint family (10%) increasing the tendency to have a nuclear family (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Family structure

It is also found that 17.50% families have two members, 62.50% families have three to five members. Whereas, 12.50% families consist six to eight members and only 7.50% families have nine or more members (Table 1).

Table 1. Family size

| Family Size | Respondents (%) |

| 2+ | 17.50 |

| 3-5 | 62.50 |

| 6-8 | 12.50 |

| 9+ | 7.50 |

The nuclear family (two adults and their children) is the main unit in urban societies in Bangladesh. In the rural areas, it is a subordinate part of an extended family, which also consists of grandparents and other relatives. A third family unit is the single-parent family, in which children live with an unmarried, divorced, or widowed mother or father. In the study site, most of the families are living in the nuclear family and those who are belonging to joint family have increased the tendency to have a nuclear family.

Social problems in the study site are in a form of poverty, inequality, resource scarcity, illiteracy, maladjustment is more significant, especially in the lower caste and marginal groups. Santal often suffer from socio-political insecurity. It is difficult and almost impossible for the poor and the minority group to escape and enter into the modernizing sector of society where discrimination on the basis of caste is less prevalent. In all classes in urban as well as in rural areas, discrimination and violence against women have also taken place. Discrimination against lower caste members, including the Santal is still a problem in the country. Since independence, many lower caste groups have mobilized politically and have achieved positions of power to organize the landless and homeless, however, have not enjoyed the same success (Hussain, 2000). In rural areas, the lower caste traditionally serves to the higher caste. This situation has aggravated caste conflict and consequently keep the poor politically and socially weak. In the study site, the ethnic people, in individual level, are deprived of their fundamental rights which are necessary for them to live in a happy and comfortable life.

Religion is an important element of culture for any group of society. Like many ethnic groups, the Santal believe in various natural spirits and forces, which control human life. The Santal worship the supernatural powers. They call their religion as Sonataon Dharma. The Santal village is a territorial unit, a collection of a few homesteads working as an administrative unit under a manjhi organization, where all its inhabitants are related to kinship or other group bonds. Santal tribe has twelve exogamous clans: (1) Hasdak, (2) Murmu, (3) Kisku, (4) Hembrom, (5) Marndi (6) Sarex, (7) Tudu (8) Baske, (9) Besra, (10) Pauria, (11) Chore, and (12) Bedea. Santal are very sincere in abiding by the rules and regulations of their own society. The basic unit of the Santal’s communal system is the village. The new generation of the Santal people is politically conscious. In order to establish their rights and interest they are participating in various political activities.

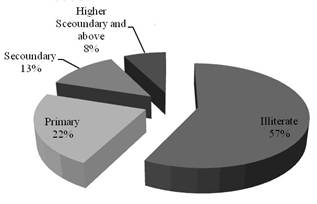

Economy is one of the key influential factors of the community’s educational situation and literary rate. The Santal are not economically solvent, but gradually more conscious about the needs of education. The Santal receive formal education in Bengali, although Bengali is not their mother tongue. With some personal guidance and encouragement they do pretty well in classroom competitions. From informal discussion the teachers told us that Santal children’s performance is competitive with the mainstream children. From Figure 3, we can get the full picture of the literacy rate of the Santal in the study site. It is notable that, the older people are illiterate whereas, comparatively young people.

Water plays one of the important roles in healthy living. Like other parts of Bangladesh Santal people consume water for drinking, cooking, washing, and bathing. Traditionally the Santal of the study site collect water from nearby ponds or tanks, but nowadays they are not using pond water for drinking, although depend on tank water for washing, bathing, and cooking (Table 2).

It is notable that the people who usually drink tube well water, sometimes compelled to drink water from alternative sources i.e., pond, river. This is happening when the tube well has gone out of water, especially in a dry season.

According to the Marxist ideology, economy is the basic structure of a society. Agriculture is then the main economic activity of the Santal community. They usually produce different types of crops i.e., rice, pulses, wheat, potatoes, bananas, pineapples, also rearing cattles and buffaloes. In a lean season, the male members of the family go out for hunting rats and rabbits in the neighboring fields and jungles to chase of their primitive semi-hunting life.

Figure 3. Educational status

Table 2. Uses of water by sources

| Sources of water | ||||||

| Ditch | River | Tank / pond | Tube well | Ring well | Total | |

| Drinking | 15% | 05% | 12.5% | 67.5% | 00 | 100% |

| Cooking and Washing | 25% | 12.5% | 42.5% | 7.5% | 12.5% | 100% |

| Bathing | 20% | 05% | 62.5% | 10% | 2.5% | 100% |

Men work mainly in the fields and women transplant the seedlings. Unlike Oron women (Naznin et. al., 2006) Santal women are however expected to involve both indoor and outdoor activities. They are economically more active than men. Santal women carry more burdens in comparison to male counterparts by involving both indoor and outdoor activities (Sultana, 2002). Although they contribute much more than the male they never claim anything for their over duty rather they are too much submissive to their husband. Some woman has contributed to the family income through craftiness such as embroidery. Women also work as a maidservant, labourer on construction sites, and street vendors. Increasingly among the educated, some women have their own jobs as a teacher, clerk, secretary. Women entrepreneurs and shopkeepings are rare. When no work is available for them, they spend the day in collecting edible leaves and fuelwoods, making nets, and catch fishes from the wetlands.

Table 3. Land ownership

| Categories | Amount | Percent |

| Landless | not occupy any land | 57.50 |

| Marginal | occupy <1 bigha | 27.50 |

| Medium | occupy 1-5 bigha | 10.00 |

| Average | occupy >5 bigha | 5.00 |

Note: 1 Bigha = 0.13 ha

The result shows that 57.50% respondents of the study site are land less, and those have land is very limited as 27.50% owning below one bigha (0.13 ha) land. The medium landowner class (10%) owns one to five bighas. And only 5.00% occupy more than five bighas of land. So it is clear that the majority are landless, and owning a small amount of land. It is also observed that land ownership is the main indicator of social status as it is the main source of their income (Table 3).

Figure 4. Sources of income

Sources of income are also one of the most important indicators of social status in the study site. It is found that 52% respondents earned income from agricultural wages. Only 20% respondents have their income from agriculture (Figure 4). Santal in the study site have traditionally settled their communities in an environment, involving agricultural practices where their livelihoods rely on. The vast majority of cultivated lands is inhabited by large groups of smallholder farmers, living in permanent villages and practicing permanent farming. It is precisely these large groups of smallholder farmers who have been, for decades, the main manager of land resources. They are still the most prominent and knowledgeable among present agricultural practices (see also Rahman et al., 2013). They also manage forests in order to get income. For example, they collect non timber forest product, though quite irregular amounts of cash income. Cash from forest products is used to purchase manufactured goods. Santal allocate their labour to various activities based on the return derived, both in terms of income, food security and minimizing livelihood risk, which allows them to adapt to annual variations and the relative inflexibility of labour requirements in agriculture. The labour demand of agriculture varies considerably throughout the year, for example, the high labour season is the time of planting and harvesting. The remaining period represents the long ‘slack’ season when the opportunity costs of labour are much lower.

There is a strong rationale and an urgent need to support Santal people, granting special attention not only to the income generation, but also to the social modes of cultivation practices and to the underlying systems of existing cultural representation and knowledge.

4. Conclusion

The Santals are mainly found in the Barind tract of Bangladesh and widely spread in the eastern part of India. They speak Austrik of Mundari language. It is said that even they are migrated for the land and shelter, insecurity always prevails in their mind. In Bangladesh they are facing many problems from time to time, such as social conflict and cultural instability. But, the Santal face never shows any expression of anger and aggressiveness despite despondency frustration. One may greatly be impressed by this distinctive attribute of character. Because their own culture and aesthetic taste have developed in such a manner.

Very few initiatives have been taken to help support the life of these ethnic minority people. There are few constitutional provisions for the protection of the ethnic minorities. According to article 27 of the constitution of the peoples Republic of Bangladesh, all citizens are equal and have equal position in law. Thus, Bangladesh could generate a multi-ethnic leadership that will bring glory for the country and protect the people from all sorts of hazards and discriminations.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Department of Anthropology, and the Department of Folklore, University of Rajshahi, Bangladesh which has been affirmed and paid an assistant this research. Many thanks are also extended to the masses on the study site where the field investigation was undertaken, who portion out their treasured time, thought and concerns.

References

- Banglapedia, 2003. Banglapedia - the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

- Banglapedia, 2012. Banglapedia - the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

- BMDA (Barind Multipurpose Development Agency), 1999. Annual Report 1999. Rajshahi, Bangladesh.

- Government of Bangladesh, 2010. Bangladesh Population Census 2010. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

- Hussain, K., 2000. ‘The Santal of Bangladesh: An Ethnic Minority in Transition’, Works Shop Paper of ENBS, Oslo.

- Karim, A.H.M. Z., 2000. ‘The Occupational Diversities of the Santals and their Socio-cultural Adaptability in a Periurban Envoronmental Situation of Rajshahi in Bangladesh: An Anthropological Exploration’, Annual Conference of Indian Anthropological society, Santiniketan, India.

- Minority Rights Group International, 2008. World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples, Bangladesh : Adivasis. [online] Available at:http://www.refworld.org/docid/49749d5841.html(accessed 2 March 2014).

- Naznin, T., S. A. Rahman, and K.M. Farhana, 2006. ‘Situation of Women Among the Ethnic Minorities: An Anthropological Study of Oraon Community in Northern Bangladesh’, Journal of the Institute of Bangladesh Studies, 29:123-128.

- Rahman, S. A., C.Baldauf, E.M. Mollee, M.A.A. Pavel, M.A.A. Mamun, M.M. Toy, T. Sunderland, 2013. ‘Cultivated Plants in the Diversified Homegardens of Local Communities in Ganges Valley, Bangladesh’, Science Journal of Agricultural Research & Management, DOI: 10.7237/sjarm/197.

- Roy, N. R., 1993. Bangalir Etihash, Adiparva. (In Bengali). Dey,s Publication , Calcutta, India.

- Roy, S.C.,1928. Oraon Religion & Customs. Culcutta, India.

- Sattar, A., 1983. In the Sylvan Shadows. Bangla Academy, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

- Sultana, A., 2002. ‘Santal Sansckrititai Khrista Dharmar Provab. Rajshahi Jelar Pachti Gramer Upor Akti Nritatic Gobeshana’, Unpublished Thesis, University of Rajshahi, Banglades.