Cyber-Bullying in the Online Classroom: Planning, Training, and Policies to Protect Online Instructors

Michael T. Eskey1, Henry Roehrich2, *

1Criminal Justice Administration, Park University, Parkville, MO USA

2Marketing & Management, Park University, Parkville, MO USA

Abstract

The advent of online learning has created the medium for cyber-bullying in the virtual classroom and also by e-mail. Bullying is commonly found in the workplace and between students in the classroom. Most recently, however, faculty members have become surprising targets of online bullying. For many educational institutions, there are no established policies nor is training provided on how to react. The current research defines the problem, reviews the findings of a cyber-bullying survey, and explores recommendations for addressing cyber-bullying through policies, training, and professional development.

Keywords

Cyber-Bullying, Bullying, Online Learning, Distance Learning

Received: March 27, 2015

Accepted: April 13, 2015

Published online: April 20, 2015

@ 2015 The Authors. Published by American Institute of Science. This Open Access article is under the CC BY-NC license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

1. Introduction

The rapid growth of online learning has experienced a subsequent rise of cyber-bullying. Bullying has typically been found in the workplace and between students in the classroom, outside of the classrooms, and in many forms of social media. In the education field, many people have been involved in bullying as either a recipient, a bully, or as a witness, in the capacity of instructors, administrators, or students. Most recently, faculty members have become targets and victims of online bullying.

In the education field, many people have been involved in bullying as either a recipient, a bully, or as a witness, in the capacity of instructors, administrators, or students. This is not surprising as the trend of students moves toward the Internet. In the fall of 2011, of the 17.7 million college students, only 16 percent were attending traditional 4-year colleges and living on campus (Allen and Seaman, 2013). For many institutions, there are not established policies or training on how to react. The multitude of state laws and high education policies are not consistent in the definition, enforcement, and punishment of cyber-bullying. The current research addresses the scope of the problem, a review of the findings of cyber-bullying related to a university with a majority of students and instructors online, and a plan for addressing the problem through policies, training, and professional development.

Communication styles of both online and face-to-face students have changed from formal, respectful, business-style letters to the informality of text message-type interactions, emoticons, and casual abbreviations such as "LOL" (laugh out loud) with the added expectation of immediate response. These trends have contributed to an isolated, albeit high-speed, communication method of learning and have contributed to an increase in cyber-bullying. Types of cyber-bullying could include cyber-assaults, libel, and misappropriation of likeness, defamation, and false light invasion of privacy. These may also include false accusations, name-calling, non-factual, high-speed-rumours and unabashed cyber-speed expressions of contempt. Personal attacks and slander are common and are directed at peers, other instructors, and college administrators.

Based on today’s college communications, social media, and personal e-mails, hundreds, even thousands of recipients can be reached in a short period of time. As noted by a number of researchers (Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J., 2011), e-mails, text-messaging, chat rooms, cellular phones, camera phones, websites, blogs, etc., contribute to the spread of derogatory and ostracizing comments about fellow students, teachers, and other individuals. This correspondence cannot be retracted easily and can be broadcast to a wider audience.

2. Focus of Research

The research intended to address four questions and issues:

1 What is the extent of online faculty cyber-bullying by students at a Midwestern university?

2 Are online instructors aware of the policies and procedures that are in place to handle issues of cyber-bullying at the institution? How have online faculty addressed the issue of cyber-bullying?

3 Was this effective?

4 Based on the results, what preventive measures, policies, and training are needed to reduce and discourage cyber bullying in online education settings?

3. Methods

For the research, cyber-bullying was defined for respondents as the use of electronic devices such as computers, iPads, cell phones, or other devices to send or post text or images intended to hurt, intimidate, or embarrass another person, to include such behaviour as:

• Flaming: Online fights using electronic messages with angry and vulgar language.

• Harassment and stalking: Repeatedly sending cruel, vicious, and/or threatening messages. A single message can constitute cyber-bullying depending on the circumstances. Often times when this occurs instructors are unprepared to react and where to seek support.

• Mobbing: A group of students cyber-bully a particular instructor.

The research focused on a little-examined area of the online faculty experience of being a victim of cyber-bullying. Few studies have focused on this phenomenon. In the fall semester of 2013, a sample of 550 online instructors were surveyed resulting in a total of 202 online faculty members (103 males and 99 females) responses (37% response rate) to a 49 question survey instrument. The survey link was distributed via university e-mail. Respondents were informed that the survey was voluntary and that their responses were confidential. Respondents included full-time and adjunct online instructors at a Midwestern university. Each respondent taught in the College of Liberal Arts and Science, the School of Business, the School of Education, and the School for Public Affairs. Instructor observations of college students in classroom settings, a baseline survey of students, conversations with instructors at other U.S. colleges, and a thorough literature review suggest student classroom uses of digital devices for non-class purposes causes learning distractions, to include online bullying. This launched a research agenda focused on studying student classroom uses of digital devices for non-class purposes, and the effects that such behaviour may have on classroom learning. The survey addressed the frequency and intensity of non-class related digital distractions in the extent of online faculty cyber-bullying by students, online faculty awareness of the policies and processes in place to handle issues of cyber-bullying at the institution, how online faculty addressed the issue of cyber-bullying, the effectiveness of how the issues of cyber-bullying is addressed; and, what preventive measures, policies, and training were needed to reduce and discourage future cyber bullying in online education settings.

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained before the survey’s administration. The survey included a cover page statement informing respondents that the survey’s completion and submission constituted their consent to participate in the survey. The survey team did not ask respondents to state their name, but researcher identified colleges and schools via the college database associated with survey responses. In addition to the authors, Cathy Taylor, J.D. contributed to the survey research.

4. Measures

Qualitative survey data results were compared statistically and demographically by respondent gender, and discipline. The analysis also compared the frequency of responses. The survey contained demographic questions to determine gender, age, ethnicity, educational level, discipline taught, years and number of courses taught, and number of years teaching online.

General demographic questions were asked in the first section of the survey; the results follow. Fifty-one percent of respondents were male; one-third of those responding possessed a terminal degree. Seventy percent of the respondents were 46 years of age or over, and 45 percent had taught online for at least 11 years. The preliminary analysis of the respondents indicated that 50 percent had personally experienced student cyber-bullying. Of these, 14 percent reported "once", 29 percent - "2 to 5 times", and 8 percent, six or more times. Additionally, 23 percent of the respondents were aware of other faculty members that had been bullied online. This small percentage may be attributed to the relative isolation of online instructors, a circumstance that does not afford the opportunity to discuss experiences with peer groups. The impact of isolation on geographically separated faculty has been documented in several studies. (Dolan, 2011; Fouche, 2006; Ng, 2006) Findings by past research support the findings that 17 – 30 percent of faculty respondents have received email or instant messaging that "threatened, insulted, or harassed" (Minor, Smith & Brashen, 2013; Smith, 2007). Many perceived "threats" were targeted at going to the chair or administration over grades or other assignment- and course-related matters. As requesting administrative review of grading is a normal process in academia, further studies may be needed to explore why this was considered bullying and whether study respondents were given adequate time by students to respond to questions about grading before threats to go to the department chair or administration began.

5. Findings

The research explored cyber-bullying through the examination of online instructors’ perceptions about cyber-bullying and perceived support. The analysis of a survey data collected from 202 online instructors addressed a number of perceptions and issues. The following section highlights the emergent themes and findings. Questions asked include: (1) what is the extent of online faculty cyber-bullying by students? (2) How have online faculty addressed the issue of cyber-bullying? (3) Are online instructors aware of the policies and processes in place to handle issues of cyber-bullying at the institution? (4) Based on the results, what preventive measures, policies, and training are needed to reduce and discourage cyber bullying in online education settings? The first main finding concerns the extent of cyber-bullying of online instructors by students. Forty-six percent of the respondents reported some type of student complaints; 15 percent involved attacks on their personal qualifications; 31 percent include student use of university e-mails to personally attack the instructor; thirty-three percent of the respondents reported being bullied more than once, and 21 percent did not feel that their problem had been handled effectively by their superiors or administration. Did respondents consider cyber-bullying a problem in higher education? From the responses, only 39 percent of respondents did not feel that cyber-bullying was a problem. While 38 percent felt that cyber-bullying of online faculty was a "slight" problem", 22 percent felt that it was a moderate to large problem. The major reasons those bullied attributed to student cyber-bullying were grade-related (48%) and assignment-related (32/8%) with some being age-related, outside work-related, gender-related or family-related.

Secondly, what was the response to the research question of "how have online faculty addressed the issue of cyber-bullying?" Of those reporting being bullied, 55 percent stated they addressed the issue themselves. Twenty three percent contacted the academic director, and 45 percent contacted either their chair or program coordinator. The possibility of a communication gap may contribute to the "non-reporting of cyber-bullying" or other course issues. For those who reported that they had been cyber-bullied, the procedure is to contact the academic director and program coordinator.

Survey responses revealed that those bullied were most likely to maintain frequent contact via e-mail with online staff members, the program coordinator, and other online adjunct instructors. Contact with other key members of the online community was somewhat infrequent with 75 to 85 percent reporting either annual contact or "never" contacting via e-mail. Certainly, not all communication needs to be based on crises situations or problems; however, the data indicated that limited e-mail communication between online instructors and key individuals in the institutional academic process contributed to the problem.

Table 1. Communication with University Personnel via Telephone by Percentage of Frequency of Contact

| Position / Frequency of Contacts (%) | Never | Annually | Once or Twice Per Term | Monthly | Weekly |

| Program Coordinator | 79 | 4 | 10 | 3 | 3 |

| Academic Director | 83 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| Department Chair | 82 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 3 |

| Assigned Mentor | 96 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Dept. Faculty Member | 86 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Online Staff Member | 84 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 1 |

| Other Adjunct | 63 | 15 | 11 | 6 | 1 |

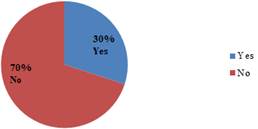

The third issue addressed whether online instructors were aware of the policies and procedures that are in place to handle issues of the cyber-bullying at the institution. While there was a formal university process of going through the Dean of Student Life or Academic Director starting with a concern form, only 30 percent of respondents affirmed that they were aware of the university having a process in place to handle cyber-bullying as shown in Figure One below.

Figure 1. Awareness That Institution Had a Process in Place to Handle Cyber-Bullying

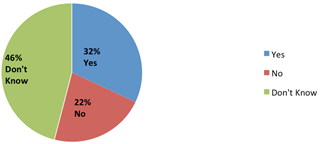

Strikingly, two-thirds of all respondents stated that they either did not know-about or did not feel that the university had resources available to help instructors properly handle a cyber-bullying situation. Seventy-one percent of all respondents stated that they were not aware that their institution had such a process in place. Respondents did not appear to know how to identify cyber-bullying or the process to follow when it occurred. A similar concern from the survey was that only 32 percent of respondents felt there were resources available to properly handle a cyber-bullying situation. That is, two-thirds of respondents either reported that they did not feel the institution had the resources to handle a cyber-bullying situation, or they "didn’t know" if they had the resources to do so as exhibited in Figure Two below.

Did respondents who were aware of the institutional policy on cyber-bullying actually utilize it? Only 10 percent of respondents reported doing so, although 51 percent reported some type of cyber-bullying. Twenty-one percent of respondents simply ignored the bullying and took no action. How was the cyber-bullying handled? As only 31 percent reported an awareness of resources available, most of the issues were handled by the instructor (31%), followed by the program coordinator (17%), the academic director (12%) and department chair (9%).

Figure 2. Felt That Institution Had Resources to Handle Cyber-Bullying

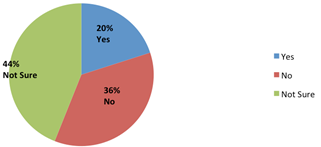

Respondent comments were mixed on the success of addressing student bullying in their online courses. The majority of respondents identified a need for university commitment in training and professional development for instructors and university-wide education to students addressing cyber-bullying prevention and consequences. Unfortunately, the study results found that respondents were reluctant to report bullying by students or faculty. As mentioned, adjunct faculty members are often working in isolation, which might affect their response to bullying as well as other course situations. Teaching online as an adjunct is competitive, and reporting course problems may be perceived by adjuncts as detrimental to being assigned to teach future classes. When asked, 36 percent did not feel reporting bullying would be held against them, 20 percent said "yes"; and 44 reported that they were not sure. Thus, two-thirds of reporting faculty were unsure or fearful about possible repercussions about reporting bullying and may be inclined not to do so to avoid penalties as shown in Figure Three below.

Figure 3. Felt that Reporting Bullying Will Be Held Against Them

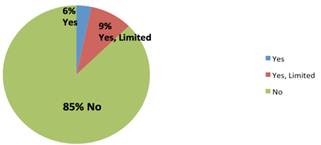

Fourth, what was the response to the research question "based on the results, what preventive measures, policies, and training are needed to reduce and discourage cyber bullying in online education settings?" Only six percent of respondents indicated they had received adequate training to manage cyber-bullying; nine percent indicated some training as shown in Figure Four below. This leaves 85 percent that had received no training to address or report cyber-bullying. Similarly, 85 percent of all respondents expressed a need for professional development training related to cyber-bullying in the university’s online training. Training and education for recognizing, addressing, and reporting cyber-bullying are key activities to ensure that cyber-bullying is properly handled and that online instructors are fully protected. From the survey results, online instructors were neither aware of their responsibilities nor were equipped to deal with situations of cyber-bullying from their students.

Faculty respondents were aware of their shortfalls. Many were aware, as recipients and targets of student bullying, and from national attention on this phenomenon, that a number of students utilize bullying in the classroom for many reasons. Six of ten respondents perceived a need for professional development for training related to bullying. One-fourth of respondents were not sure if they needed professional development in this area. Instructors were provided in-depth training in facilitation, pedagogy, and the learning management system, but cyber-bullying and the process of reporting is neither addressed in initial training nor provided in separate professional development training.

Figure 4. Received Specific Training in Responding to or Reporting Cyber-Bullying

6. Recommendations

In light of the survey results, what is the answer to the research question: "what preventive measures, policies, and training are needed to reduce and discourage cyber bullying in online education settings?" The role of the administration will first be examined and then take away points will be proffered. There is an implication that creating policies and resources that educate both students and faculty on the institutional definition of cyber-bullying is needed. Additionally, online instructors must be trained on how to identify cyber-bullying, how to react appropriately and professionally to being the victim of cyber-bullying, who to go to when cyber-bullying is experienced, and the consequences to students and faculty who are found to be cyber-bullying others is imperative. Please note that the authors of this paper did not intend to provide legal advice or to create an attorney client relationship in writing this paper or in making the following recommendations. Cyber-bullying can create many challenges for online instructors. Bullying can be student against student, a group of students against one student (mobbing) or it can be directed upwards, toward the instructor, in upwards bullying. Upwards bullying has been explored in managerial settings by Branch, et al (2007); the physical and psychological impact of mobbing in an employment setting has been studied by Leyman and Gustafsson (1996). Upwards bullying can be one student against an instructor or a group of students against the instructor (upwards mobbing).

Bullying of an instructor can involve challenges to teaching skills, credentials, a lack of experience of new instructors, and also spring from challenges to the subject matter, the textbook choice, and exam questions. Sometimes, bullying occurs early in the term over a small point value assignment and escalates. Disputes over grading are often the genesis of the bullying. Clear rubrics and adherence to those rubrics in grading may be one way for faculty to proactively avoid these disputes. A university policy requiring rubrics for all assignments and training on drafting rubrics for faculty, especially new or adjunct instructors could be beneficial.

7. Faculty Action Plan for Cyber-Bullying

A faculty member when confronted with the stress and anxiety that can accompany a cyber-bullying situation needs to have a systematic and timely approach to handling the situation. A Faculty Action Plan for addressing conflict in faculty cyber-bullying was developed from the author’s actual experience in handling cyber-bullying and the ACHIEVE model. The ACHIEVE model was designed by Paul Hersey and Marshall Goldsmith for determining why problems have occurred and then developing change strategies aimed at solving those problems (Hershey, et al, 2012)

The faculty member should take a situational leadership role in addressing cyber-bullying. Situational leadership is based on the principle that there is not one leadership style that works in all situations (Blanchard et al, 2003). The faculty member needs to make decisions as to what has to be done concerning cyber-bullying, how it is to be done and when it needs to be done in order to address the problem (Irgens, 1995). If conflict occurs through cyber-bullying then the faculty member should have a process that involves listening, communicating, recognizing and encouraging. The Faculty Action Plan strategy is an organized process to counter cyber-bullying and requires an assessment of the situation in addition to the utilization of resources available for the faculty member at an institution.

Confronting a student’s inappropriate behaviour is difficult and the faculty member needs to recognize their latitude of authority; understand that they may not have all the answers; and recognize that they can make errors (Cooper & Pardee, 2011).In order to attain the desired results to cyber-bullying, the faculty member should address each of the supports that are connected in the network of the Faculty Action Plan. The connecting supports provide a diagram that crates a path for reducing the risk of mishandling of a visible cyber-bullying situation. The first area to consider is aptitude of the faculty member. Aptitude is the capability of the faculty member to address the cyber-bullying situation successfully. A faculty member may be capable of facilitating a course, but there may be unexpected challenges in maintaining a learning environment that is disrupted by a cyber-bullying episode. The aptitude of a faculty member can result from the expertise in handling conflict that has resulted from past experience and also through the participation in professional development activities. Conflict resolution and communication skills training in departmental meetings can have a great importance for faculty in healthy conflict resolution (Kasik & Kumcagiz, 2013). The expertise of a faculty member can be gained through the discussion of cyber-bullying situations in departmental meetings and from consulting with peers that are knowledgeable in the area of conflict management. Reducing the risk of cyber-bullying can be accomplished by providing clear goals, frequent feedback, opportunities to discuss concerns or feelings, involvement in problem-solving, and decision making and coaching (Farmer, 2005). If the faculty member has problems with precision or clarity as to addressing cyber-bullying while facilitating a course, it could lead to a learning environment that fuels additional cyber-bullying situations. The faculty member should provide clear and concise communication through open communication channels when reporting and addressing cyber-bullying incidents to administration. In order to report a situation, there needs to be an understanding by the faculty member of when, what and how cyber-bullying should be addressed and in what timeframe. Encouragement for the faculty member by the organization’s support systems to ask questions for clarification is essential to defining a cyber-bullying incident.

Figure 5. Faculty Action Plan for Addressing Cyber-Bullying

The next step for the faculty member is to seek assistance within the organization. The support system should be readily available for the faculty member so that timely advice can be retrieved and strategic approaches can be considered. Timing is important in addressing and resolving a cyber-bullying situation. When there is confusion as to what steps to take in addition to stress resulting from uncertainty of future outcomes, mistakes fuelling the cyber-bullying situation could occur. If there is lack of support in the organization for the area of cyber-bullying, then cost effective measures need to be introduced through the proper channels. If the instructor does not have the ability to handle a cyber-bullying issue, the instructor may want to utilize a mentoring program, if one is available. Effective mentoring programs can prepare the instructor to understand and address cyber-bullying situations through role playing and problem solving activities that offer different scenarios. Teaching effective conflict resolution skills in a mentoring program can help to prevent major problems as well as the increase of existing problems (Kasik & Kumcagiz, 2014).The legality of the approach by the faculty member and those involved in the cyber-bullying activities should be addressed by legal experts and administration in the organization. With this in mind, the faculty member should be able to access the contact information for the legal experts in the organization without an extensive search and be able to meet with them (Cooper & Pardee, 2011). In order to avoid a legal conflict, there should also be professional development activities that communicate what steps should be taken and what actions are acceptable. Detailed documentation needs to be completed so that if there is a legal process, then the faculty member can support their actions during cyber-bullying. The actions of the faculty member should take into account the law, court decisions and organizational policies. This could be discussed when the legal experts are consulted. The faculty member will want to consider the motivation of the students in the class that are involved in cyber-bullying. Not all students are equally motivated and this could create an issue with how to address the situation. It can be essential to handling a cyber-bullying situation by analysing and then communicating the rewards and consequences of appropriate behaviour towards the faculty member and a quality learning environment (Hershey, Blanchard & Johnson, 2012).The consequences for inappropriate behaviour could include a failing grade or removal from the class. This information needs to be clarified in the course material and by the instructor through written and verbal communication. The failure of a faculty member to communicate specific information during the assessment process can have an effect on performance and student response (Saxon & Morante, 2014). If the level of student performance is affected by poor assessment techniques, there could be conflict leading to the possibility of additional cyber-bullying. A student that is confused as to their performance may become frustrated and confused with how to approach the instructor. Therefore, open and honest communication channels along with documentation in the timely assessment of performance can be used to reduce the frustration and provide direction for improvement. Finally, it should be considered that internal and external factors in the course can influence cyber-bullying and should be addressed. Taking the initiative to dealing with problematic factors could correct the current situation, or it could reduce the risk of additional students taking a part in cyber-bullying behaviour. The overall success in dealing with cyber-bullying relies on the faculty member to follow the Faculty Action Plan, while utilizing the available resources, and communicating effectively during the entire process.

8. Take-Away Points

In formal and informal discussions and lectures, universities should "try to make sure the students understand that number one, it is against the law; number two, it’s against school policy" to engage in bullying activity (Breitenhaus, 2010). Repetitive education and enforcement will ensure that students understand that the administration is clearly behind anti-bullying/anti-cyber-bullying programs. There are real penalties for cyber-bullying. The consequences must be clarified for students. The fear and threat of suspension, expulsion, criminal prosecution, and/or civil lawsuits should normally deter the majority of students from such behaviour. A myriad of ways for colleges and universities to help prevent incidents of cyber-bullying exist. Suggestions will be enumerated as follows.

First, as noted earlier, policies and resources should be created and routinely shared with faculty and students. Policies could include the institutional definition of cyber-bullying, how to identify cyber-bullying, instructions for faculty on how to react appropriately and professionally to being the victim of cyber-bullying, who in the administration to go to when cyber-bullying is experienced, and the consequences to students and faculty who are found to be cyber-bullying. The possibility for faculty to cyber-bully students exists although the authors have never experienced this, and the administration should include that in training to protect all parties. In particular, the administrators could enact a policy of instructing and warning students of improper online behaviour while participating in an online course. Make it mandatory that students read it, understand it, and agree to comply with it. Possible features could include graduated consequences and remedial actions, procedures for reporting, and procedures for investigating. Specific language to the Tinker standard (Tinker, 393 U.S. 503) regarding circumstances when a student’s speech or behaviour results in a substantial disruption of the learning environment could be appropriate but needs to be based on legal counsel.

While current instructors have not received such training in their initial online training, this can be added to future initial training for newly hired online instructors. Additionally, professional development classes can be developed and provided for current online instructors for recognizing, addressing, and reporting cyber-bullying. At the authors’ school, the University Catalogue (Student Conduct Code) addresses a number of behaviours that are not permitted, but does not mention anything related to electronic devices or communication. This could be added to clarify the rules to students.

Second, administrators should add cyber-bullying training to new faculty orientation or training for online faculty so that faculty will be aware of what to look for, how to address it, and how to report it. Emphasize and assure the instructors that this will have no negative repercussions on them; in fact, they are encouraged to report all cyber-bullying. It is assumed that all online instructors are proficient in the facilitation of their course using the university learning management system; but, a proficiency in other methods used by students in cyber-bullying such as text-messaging, instant messaging, chat rooms, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, for example, are not assumed and may actually hinder some instructors in the recognition of potential problems. Third, if the institution has a resource internet repository for instructors, place detailed information on addressing and reporting bullying.

Fourth, the administration could create a professional development course, webinar, or informative e-mail that discusses cyber-bullying resources and will be provided to all instructors. For example, at the authors’ institution, all instructors are required to take a six week training course prior to teaching online; however, 550 instructors have already completed this training and would not benefit by adding a bullying portion to this course retroactively. The university needs additional training or resources on cyber-bullying that are available to all instructors. Fifth, administrators could require definitions of cyber-bullying and descriptions of the consequences for doing so in the syllabi for all classes as a method of early deterrence. No student would want to face probation, expulsion, or criminal charges that will be detrimental to their entire career plan.

Sixth, require that students and instructors keep all documentation of cyber-bullying events. In the grade school setting, without proper documentation, the extent of the problem is largely unknown to various levels of stakeholders including school board, parents, community members, and campus-based personnel (DOE Report, 2011). The same can be said of higher learning. Reviewing the challenges experienced by secondary schools in dealing with cyber-bullying and solutions found could be useful in application to higher learning.

References

- Allen, J.E., &J. Seaman (2013). Changing course: Ten years of tracking online education in the United States. Babson Park, MA: Babson Survey Research Group and Quahog Research Group. Retrieved fromhttp://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/changingcourse.pdf

- Blanchard K., P. Zigarmi. &D. Zigarmi (2003).Situational Leadership II. The Ken Blanchard’s Companies, San Diego, CA, USA.

- Branch, S., S. Ramsay, &M. Barker (2007). Managers in the firing line: Contributing factors to workplace bullying by staff- an interview study. Journal of Management & Organization, 13, 264 281.

- Breitenhaus, C. (2010). Addressing Cyber-bullying in Higher Education, Peter Li Education Group, October, 2010.

- Cooper, M., &H. Pardee (2011). Managing conflict from the middle. New Directions for Student Services, Winter 2011, (136), 35-42

- Dolan, V. (2011). The isolation of online adjunct faculty and its impact on their performance. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 12(2). Retrieved fromhttp://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/793/1691

- Farmer, L., (2005). Situational Leadership: a model for leading telecommuters. Journal of Nursing Management, Nov 2005, 13(6), 483-489.

- Fouche, I. (2006). A multi-island situation without the ocean: tutors’ perceptions about working in isolation from colleagues. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning,7(2). Retrieved fromhttp://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/295/640

- Hersey, P., Blanchard, K. & Johnson, D. (2012). Management of Organizational Behaviour, 10 ed. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. (2011). High-tech cruelty, Educational Leadership, 68(5), 48-52.

- Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. (2012). State cyber-bullying laws: A brief review of state cyber-bullying laws and policies. Retrieved fromhttp://www.cyberbullying.us/Bullying_and_Cyberbullying_Laws.pdf

- Irgens O.M. (1995) Situational leadership: a modification of Hersey and Blanchard. Leadership and Organizational Development Journal, 16 (2), 36–42.

- Kasik, N., & Kumcagiz, H., (2014). The effects of the conflict resolution and peer mediation training program on self-esteem and conflict resolution skills. International Journal of Academic Research, Jan 2014, 6(1), 179 – 186.

- Leyman, H., & Gustafsson, A. (1996). Mobbing at work and the development of post-traumatic stress disorders. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2), 251-275.

- Minor, M.A., Smith, G.S., Brashen, H. (2013). Journal of Educational Research and Practice, 3(1), 15–29.

- Saxon, P. & Morante, E. (2014). Effective Student Assessment and Placement: Challenges and Recommendations. Journal of Developmental Education, Spring2014, 37(3), 24-31.

- Smith, A. (2007, January 19). Cyber-bullying affecting 17% of teachers, poll finds. The Guardian. Retrieved fromhttp://www.guardian.co.uk/education/2007/jan/19/schools.uk

- Tinker v. Des Moines Independent. Community. Sch. Dist., 393 U.S. 503 (1969)

- U.S. Department of Education. (2011). Analysis of State Bullying Laws and Policies (Contract Number ED-CFO-10-A-0031/0001). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.