Patterns of Parasitic Infestations Among Food Handlers in Dubai

Al Suwaidi A. H. E.1, Hussein H.2, *, Al Faisal W.2, El Sawaf E.3, Wasfy A.4

1Preventive Medicine Department, Ministry of Health, Dubai, UAE

2School and Educational Institutions Health Unit, Health Affairs Department, Primary Health Care Services Sector, Dubai Health Authority, Dubai, UAE

3Health Centers Department, Primary Health Care Services Sector, Dubai Health Authority, Dubai, UAE

4Statistics and Research Department, Ministry of Health, Dubai, UAE

Abstract

Background: food handlers i.e. any person who handles food, regardless whether he actually prepares or serves it, play an important role in the transmission and, ultimately, prevention of food borne disease. Information regarding food handlers’ practices is a key to addressing the trend of increasing food borne illnesses. Objectives: To study prevalence, and epidemiological and clinical characteristic of parasitic infestation among food handles in Dubai. Methodology: A cross sectional study was carried out. The study was conducted in Dubai city, the second largest city in U.A.E. Study was carried out in Dubai Municipality clinic which is the only authorized place for issuing medical fitness card for food handlers in Dubai. The study included food handlers attending Dubai municipality clinic for issuing medical fitness card. An appropriate sample size was calculated according to the sample equation obtained by using computer program Epi Info Version 6.04. The minimum sample size required was 420 food handlers. The study sample was 425 food handlers with 100% response rate. A systematic random sample procedure was carried out. Considering that filling the questionnaire was taking about 20-30 minutes, every 10th person was involved to select nearly 10 food handlers a day until accomplishment of the required sample size. Results: that 1.2% reported positive previous test for parasites, 60% had recurrent parasitic infection for three times or more. Results of fecal examination revealed a prevalence of parasitic infection of 2% food handlers. current or recurrent parasitic infection by socio-demographic data and history of training. Those more likely to have parasitic infection are workers in renewal status (OR =1.59), males (OR = 2.39) from Indian and South East of Asia in contrast to other nationalities (OR =7.56 and 3.08 respectively), working as bakers or in restaurants in contrast to home maid category (OR = 6.97 and 2.90 respectively) with income <1000 or 1500-<2000 AED in contrast to 2000+ AED (OR = 2.10 and 2.23 respectively). Conclusion: Parasitic infection rates among food handlers in Dubai is not that common and lower even than its rate in the general populations. Hygienic practice and parasitic infection rate among food handlers in Dubai significantly correlated with some socio demographic factors e.g. sex, type of work, training history, educational level and income. Recommendations: Re-certification, to keep up with new food technology and safe food-handling practices, and to ensure the safety of foods for consumers.

Keywords

Parasitic Infestations, Food Handlers, Dubai

Received:May 11, 2015

Accepted: May 18, 2015

Published online: July 8, 2015

@ 2015 The Authors. Published by American Institute of Science. This Open Access article is under the CC BY-NC license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

1. Introduction

Food handlers i.e. any person who handles food, regardless whether he actually prepares or serves it, play an important role in the transmission and, ultimately, prevention of food borne disease.(1) Information regarding food handlers’ practices is a key to addressing the trend of increasing food borne illnesses. The prevention of food borne disease requires the cooperation of all those who interact in the food chain.(2)

Intestinal parasites are the causative agents of common infections with significant public health problems in developing countries. They infect a total of 3.5 billion people globally and kill almost 450 million every year. Main symptoms of these infections are gastrointestinal, such as abdominal pain and appetite change; they may also cause anemia and physical and mental problems such as growth retardation in children.(3)

Parasites are organisms that obtain nourishment and shelter from other organisms. In this association, the parasite derives all the benefits, whereas the host may either be unaffected or suffers harmful consequences, with the development of a parasitic disease. The parasites responsible for these diseases are called obligate if they can live only in association with a host and facultative if they can live either in a host or independently.(4) Parasitic diseases represent one of the most common types of human infection throughout the world and are still the cause of much human morbidity and mortality.(5)

It was reported that globally, millions of adults and children in Africa, South and Central America, Asia, and parts of Europe suffer from parasitic infections such as Ascaris lumbricoides (1.2 billion), Trichuris trichiura (795 million), hookworms (Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus) (740 million)(6) Entamoeba histolytica (50 million)(7) and Giardia lamblia (2.8million).(8) Parasitic diseases were found to be with higher prevalence in developing countries, especially in areas with inadequate sanitation. Some of these diseases are restricted to tropical and subtropical regions. About one third of the world, "more than two billion people", are infected with intestinal parasites,(9) where 300 million people are severely ill with these worms and of those, at least 50% are school-age children.(9)

In developing countries, prevalence rates range from 30-60%, as compared to ≤ 2% in the developed countries.(10) It is well known that ascaris lumbricoides is the largest and the most common helminthes parasitizing the human intestine and currently infects about 1 billion people worldwide(11) while Hymenolep is nana is found to be the most common parasitic cestode prevalent globally. (12) Giardiasis, is found to be the most prevalent protozoan parasite worldwide with about 200 million people being currently infected and is well known to be caused by Giardia lamblia.(12,13) Blastocystis hominis whose parasitic status is under debate is another common intestinal protozoan.(11) Many epidemiological data on the prevalence of intestinal parasitosis are available for developing areas, (14,15,16) in industrialized countries where intestinal parasitosis are usually not notified, few data are reported in the literature.(16) Information is available for some European nations on the WHO website concerning only the number of cases/year and the incidence of amoebiasis and giardiasis, since 1995 to 2006.(17)

It was proved that geographical distribution of intestinal parasites is influenced by the existence of suitable hosts such as animals and insects in sufficient numbers, as well as the need for favorable external environmental conditions such as suitable soil, irrigation, sewage, rainfall, humidity, and temperature. The prevalence of intestinal parasitic infection of human may also be related to several human factors such as, age, gender, occupation, methods of defecation, and habitats.(18) It was reported that one fifth of Iran’s population was infected with intestinal parasite infections.(19) According to recent reports, the prevalence rates of the intestinal parasite infections among food handlers were 29% in Iran, (20) 29.2% in Mumbai, (21)41.1% in Ethiopia,(22) 31.94% in Makkah During Hajj Season,(23) 29.4% in Sudan, (24) 52.2% in Anatolia,(25) 33.9% in Qatar,(26) 28.7% in Mukalla, Yemen(27) and 38.2% in Brazil.(28)

2. Objectives

To study the prevalence, and epidemiological and clinical characteristic of parasitic infestation among food handles in Dubai.

3. Methodology

A cross sectional study was carried out. The study was conducted in Dubai city, the second largest city in U.A.E. Study was carried out in Dubai Municipality clinic which is the only authorized place for issuing medical fitness card for food handlers in Dubai. The study included food handlers attending Dubai municipality clinic for issuing medical fitness card. An appropriate sample size was calculated according to the sample equation obtained by using computer program Epi Info Version 6.04. The minimum sample size required was 420 food handlers. The study sample was 425 food handlers with 100% response rate. A systematic random sample procedure was carried out. Considering that filling the questionnaire was taking about 20-30 minutes, every 10th person was involved to select nearly 10 food handlers a day until accomplishment of the required sample size. A systematic random sample procedure was carried out. Considering that filling the questionnaire was taking about 20-30 minutes, every 10th person was involved to select nearly 10 food handlers a day until accomplishment of the required sample size. The data was collected through face-to-face interviews (Appendix, II) using structured questionnaire after Tonder Izanne et al., (2) and WHO. (11) The questionnaire was reviewed by community medicine consultants to review the face and content validity. Reliability of the questionnaire using cronbach's alpha with Guttmann split half reliability coefficient was carried out.

4. Results

Table 1 showed that 1.2% reported positive previous test for parasites, 60% had recurrent parasitic infection for three times or more. Results of fecal examination revealed a prevalence of parasitic infection of 2% food handlers.

Tables 2 didn’t show significant differences in the mean hygienic practices among parasitic infection group whether current or recurrent.

Table 1. Parasitic infection among food handlers in Dubai.

| No. | % | ||

| Recurrent parasitic Infection | No | 114 | 26.8 |

| 1-2 | 56 | 13.2 | |

| 3-4 | 139 | 32.7 | |

| 5-10 | 116 | 27.3 | |

| Result of fecal examination | Negative | 416 | 97.9 |

| Giardia lamblia (GL) | 7 | 1.6 | |

| Strongyloides stercoralis (SS) | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Ascaris lumbricoides (AL) | 1 | 0.2 | |

Number of workers= 425

Table 2. Recurrent infection and hygienic practices of food handlers in Dubai.

| Recurrent infection | No. | Personal hygienic practices | General hygienic practices | Cooking hygienic practices | Total score | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Yes | 311 | 71.85 | 6.90 | 87.74 | 6.22 | 90.24 | 7.71 | 82.04 | 5.07 |

| No | 114 | 70.37 | 8.66 | 86.75 | 10.76 | 89.52 | 6.39 | 80.94 | 5.80 |

| Mann-Whitney test | 0.78 | 0.54 | 1.66 | 1.74 | |||||

| P value | 0.435 | 0.589 | 0.069 | 0.083 | |||||

Number of workers= 425

Table 3. Parasitic infection among food handlers by socio-demographic data and Training.

| Number of workers= 425 | Current\Recurrent parasitic infection | OR | P value | 95% CI | |||||

| No (110) | Yes (315) | ||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | LCL | UCL | ||||

| Status | New | 39 | 32.5 | 81 | 67.5 | 1.00 | |||

| Renewal | 71 | 23.3 | 234 | 76.7 | 1.59 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 2.53 | |

| Age | ˂25 | 32 | 29.1 | 78 | 70.9 | 1.00 | |||

| 25- | 34 | 26.0 | 97 | 74.0 | 1.17 | 0.690 | 0.64 | 2.15 | |

| 30- | 34 | 25.0 | 102 | 75.0 | 1.23 | 0.565 | 0.67 | 2.25 | |

| 40+ | 10 | 20.8 | 38 | 79.2 | 1.56 | 0.376 | 0.65 | 3.80 | |

| Sex | Male | 81 | 22.8 | 274 | 77.2 | 2.39 | 0.001 | 1.40 | 4.09 |

| Female | 29 | 41.4 | 41 | 58.6 | 1.00 | ||||

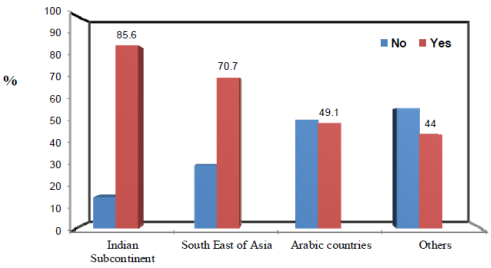

| Nationality | Indian | 32 | 14.4 | 190 | 85.6 | 7.56 | 0.000 | 3.15 | 18.11 |

| South East Asia | 36 | 29.3 | 87 | 70.7 | 3.08 | 0.019 | 1.28 | 7.42 | |

| Arab | 28 | 50.9 | 27 | 49.1 | 1.23 | 0.856 | 0.47 | 3.17 | |

| Others | 14 | 56.0 | 11 | 44.0 | 1.00 | ||||

| Education | Below secondary | 14 | 26.4 | 39 | 73.6 | 1.17 | 0.796 | 0.54 | 2.55 |

| Secondary | 56 | 23.6 | 181 | 76.4 | 1.36 | 0.251 | 0.82 | 2.25 | |

| University\ Higher | 40 | 29.6 | 95 | 70.4 | 1.00 | ||||

| Occupation | Baker and confectioner | 3 | 11.5 | 23 | 88.5 | 6.97 | 0.016 | 1.59 | 30.52 |

| Cooks and kitchen helper | 35 | 29.7 | 83 | 70.3 | 2.16 | 0.172 | 0.84 | 5.54 | |

| Restaurant | 62 | 23.8 | 198 | 76.2 | 2.90 | 0.032 | 1.18 | 7.16 | |

| House maid | 10 | 47.6 | 11 | 52.4 | 1.00 | ||||

| Duration of work (years) | ˂1 | 16 | 30.2 | 37 | 69.8 | 1.00 | |||

| 1- | 28 | 23.5 | 91 | 76.5 | 1.41 | 0.462 | 0.64 | 3.07 | |

| 3- | 29 | 23.6 | 94 | 76.4 | 1.40 | 0.463 | 0.64 | 3.05 | |

| 5+ | 37 | 28.5 | 93 | 71.5 | 1.09 | 0.957 | 0.51 | 2.31 | |

| Monthly income (AED) | ˂1000 | 17 | 21.0 | 64 | 79.0 | 2.10 | 0.040 | 1.03 | 4.30 |

| 1000- | 36 | 24.8 | 109 | 75.2 | 1.69 | 0.079 | 0.95 | 3.01 | |

| 1500- | 18 | 20.0 | 72 | 80.0 | 2.23 | 0.022 | 1.11 | 4.49 | |

| 2000+ | 39 | 35.8 | 70 | 64.2 | 1.00 | ||||

| Training | No | 16 | 21.3 | 59 | 78.7 | 1.35 | 0.322 | 0.74 | 2.47 |

| Yes | 94 | 26.9 | 256 | 73.1 | 1.00 | ||||

Table 3 shows current or recurrent parasitic infection by socio-demographic data and history of training. Those more likely to have parasitic infection are workers in renewal status (OR =1.59), males (OR = 2.39) from Indian and South East of Asia in contrast to other nationalities (OR = 7.56 and 3.08 respectively), working as bakers or in restaurants in contrast to home maid category (OR = 6.97 and 2.90 respectively) with income <1000 or 1500-<2000 AED in contrast to 2000+ AED (OR = 2.10 and 2.23 respectively).

Figure 1. Parasitic infection among food handlers by nationality.

Table 4. Current and Recurrent parasitic infection among food handlers according to home (resident in Dubai) environmental factors in Dubai.

| Current\Recurrent parasitic infection | OR | P value | 95% CI | ||||||

| No (110) | Yes (315) | ||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | LCL | UCL | ||||

| No. of toilets | one two or more | 71 39 | 22.1 37.5 | 250 65 | 77.9 62.5 | 2.11 1.00 | 0.002 | 1.31 | 3.40 |

| Crowding index | ≤5 ˃5 | 96 14 | 25.0 34.1 | 288 27 | 75.0 65.9 | 1.00 0.64 | 0.204 | 0.32 | 1.28 |

| Good ventilation | Yes No | 108 2 | 25.7 40.0 | 312 3 | 74.3 60.0 | 1.00 0.52 | 0.468 | 0.07 | 4.50 |

Number of workers= 425

Table 5. Hygienic practices and parasitic infection of food handlers in Dubai.

| Hygienic Practices | Current\Recurrent parasitic infection | OR | P value | 95% CI | |||||

| No (110) | Yes (315) | ||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | LCL | UCL | ||||

| Personal | Good (221) Fair or bad (204) | 56 54 | 25.3 26.5 | 165 150 | 74.7 73.5 | 1.00 0.94 | 0.790 | 0.61 | 1.46 |

| General | Good (233) Fair or bad (192) | 68 42 | 29.2 21.9 | 165 150 | 70.8 78.1 | 1.00 0.47 | 0.087 | 0.94 | 2.29 |

| Cooking | Good (294) Fair or bad (131) | 70 40 | 23.8 30.5 | 224 91 | 76.2 69.5 | 1.00 1.71 | 0.144 | 0.45 | 1.12 |

| Total | Good (225) Fair or bad (200) | 50 60 | 22.2 30.0 | 175 140 | 77.8 70.0 | 1.00 0.67 | 0.068 | 0.43 | 1.03 |

Number of workers= 425

Table 4 shows current and recurrent parasitic infection by home environmental factors.

Those with one toilet had significantly higher risk of parasitic infection compared to workers with two or more toilets (OR = 2.11).

Other environmental factors and hygienic practices (table 5) didn’t show significant association with parasitic infection.

5. Discussions

This study reflects that about 91% of the study sample reported illness with the need for management, and about 98.8% were referred to medical examination. This means that there is good application of follow up, supervision and monitoring system applied so far. In cut wound incidences, about 99.5% of the cases were reported to the management with use of moisture proof dressing. A study done in 2009(29), about 93% of the food handlers call in sick and stay home if they had a fever, an upset stomach, or diarrhea, 55% wash an infected cut or burn on finger or hand well with soap and water; cover it with an impermeable cover and a single use glove.

Current study reflects adherence to formal cleaning schedule among almost 96% of the study sample with nearly one third who are regularly cleaning food preparation surfaces. Hot water and detergents are adequately saved. These figures were similar to another study done in India about health status and personal hygiene among food handlers in Wardha District of Maharashtra,(30) where the kitchen surfaces were found to be clean in 73.13% of the food establishments and were being cleaned by soap & detergents (61.87%). While another study done in South Africa,(31) found no formal cleaning schedule in place in all the outlets, but more than two thirds reported that surfaces were cleaned under all the circumstances and more than three quarters of workers used hot water and detergent. In two different studies, development of cleaning and disinfection procedures was found among 12.8% and 54.8% respectively among Turkish and Iranian food handlers.(32,33)

Concerning cooking practices among food handlers, the study showed that more than three quarters of the participants wash their hands before and during food preparation and clean surfaces and equipment’s used for food preparation before re-using, while about three quarters were always using separate utensils and cutting-board when preparing food. Rules abreast with high level of awareness among food handlers are behind these high figures. The figures revealed by the current study elaborated same mistakes among food handlers concerning reheating cooked foods, thawing frozen foods, storing left over foods.

The most common hygiene mistakes made by the staff working in food and beverage firms were made during preparation, cooking, cooling and re-heating phases, cross-contamination mistakes, personal hygiene mistakes and mistakes related to post cooking internal temperature controls and to time-temperature procedures.(34) In compliance with our results it was found that 96% of a study workers in USA(29) sanitized cutting boards, meat slicers, knives, and other utensils after each use, 91% used to wash hands before preparing food and used to store leftover foods (59%). In Sicily, Italy,(35) a study about food handling nurses revealed that around 78% wash hands before and after handling unwrapped and raw foods, while 77.3% and 83.6% always wash their hands before and after touching food, respectively. About 63.1% of the respondents were always separating utensils for cooked and raw foods. Thawing frozen food at room temperature proved to be an extensively used practice, 10.5% only of the nurses stating that they occasionally applied this procedure. A study done in (2005)(36) to assess food hygiene among food handlers in a Nigerian university campus showed that the practice of storing and reheating left overs was as low as 14.7% of the respondents; as well as a very low frequency of hand washing. Only 48% had received health education about sharing of utensils for raw and cooked foods and thawing of.

The rate of parasitic infection among food handlers is expected to be much lower than that prevalent in the community. Current study revealed that the prevalence of parasitic infection among food handlers was 2%. In another study done by Khurana (2008)(37) among food handlers in a tertiary care hospital of North India , during the years 2001-2006, it was found that the rate of parasitic infections was 1.3% to 7%. Different figures of parasitic infection in different studies were recorded as follow: India, (9.7%) (38) Riyadh Saudi Arabia (12.8%),(39) Amritsar City, India (12.9%),(40) Mukalla, Yemen,(28.7%),(27) Al-Khobar, Saudi Arabia, (31.4%),(41) Makkah During Hajj Season (31.94%),(23) Qatar 3.9%,(26) Brazil(38.2%),(28) Ethiopia (41.1%),(22) Irbid (48.0%),(42) Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (50.15%)(43) and Abeokuta, Nigeria, (97%),(44) In Nigeria, such a high prevalence of intestinal parasites is largely due to poor personal hygiene practices and environmental sanitation, lack of supply of safe water, poverty, ignorance of health-promotion practices, and impoverished health services. These differences might be explained due to differences in gender, nationality, type of work, standards of education, wages, personal hygiene awareness and practices, policies of adhering to personal hygiene measures in between different studies. About 84.7% of workers had previous test for parasites which reflects high level of awareness about the importance of doing that test as a pre-employment examination in their occupation. In the present study the overall hygienic score has a mean score percentage value of (81.74% ± 5.29 of the maximum) with lowest score for personal hygiene (71.45% ± 7.43 of maximum), which might be a consequence of some violations committed by some workers such as neglecting trimming nails, putting jewelries, or neglecting hand washing after smoking or handling money. Cooking recorded the highest score (90.05% ± 7.38 of maximum). These results are found not complying with that of a study done in Italy(35) where the total score was 53.2% of the maximum possible score. A study done in Egypt(45) to assess hand washing facilities, personal hygiene and the bacteriological quality of hand washes in some groceries and dairy shops in Alexandria, showed personal hygiene with a mean score percentage of only 31.0% ± 9.2. In KAP study among food handlers, Turkish workers(46) recorded score of hygiene practice as 48.4% ± 8.8.

6. Conclusions

Parasitic infection rates among food handlers in Dubai is not that common and lower even than its rate in the general populations. Hygienic practice and parasitic infection rate among food handlers in Dubai significantly correlated with some socio demographic factors e.g. sex, type of work, training history, educational level and income.

Recommendations

Re-certification, to keep up with new food technology and safe food-handling practices, and to ensure the safety of foods for consumers. It is also important to monitor food handling practices and to develop science-based food-safety inspection guidelines. – Identify and address language barriers, literacy issues and individual testing needs prior to course delivery. – Provide train-the-trainer sessions to promote interactive adult teaching strategies such as group discussions, role playing, demonstrations (proper use of cooking thermometers) and practice sessions, (e.g. proper hand washing). – Target business owners, supervisors and kitchen managers, also should take the Food Handler Certification (FHC) course in order to support newly introduced back to work practice changes. Developing food borne diseases surveillance and notification program and carrying out competent statistical analysis and addressing for the problem.

References

- Isara AR and Isah EC.Knowledge and practice of food hygine and safety among food handlers in fast food restaurants in Benin City, Edo state, Niger. Postgraduate Medical Journal 2009; 16(3):207-212.

- 34. World Health Organization (2000). Food safety: Resolution of the Executive Board of the WHO. 105th session, EB105.R16 28 January, 2000.

- Ramos JM, Reyes F and Tesfamariam A. Intestinal parasites in adults admitted to a rural Ethiopian hospital: Relation ship to tuberculosis and malaria. Scand J Infect Dis 2006; 38(6-7):460-462.

- Murray PR, Rosenthal KS, Kobayashi GS and Pfaller M. Medical microbiology. 4th ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby, 2002.

- Martínez S, Restrepo CS, Carrillo JA, Betancourt SL, Franquet T, Varón C, Ojeda P and Gime´nez A. Thoracic Manifestations of Tropical Parasitic Infections: A Pictorial Review1. Radiographics 2005; 25(1): 135–155.

- De Silva NR, Brooker S, Hotez PJ, Montresor A, Engels D and Savioli L. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: updating the global picture. Trends Parasitol 2003; 19(12):547-551.

- Stanley SL and Reed SL. VI. Entamoeba histolytica: parasite-host interactions. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 2001; 280(6): 1049-1054.

- Ali SA and Hill DR. Giardia intestinalis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2003; 16(5):453-460.

- WHO. Schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminth infections–preliminary estimates of the number of children treated with albendazole or mebendazole. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2006; 81(16):145-164.

- Guerrant RL and Bobak DA. Bacterial and protozoal gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med 1991; 325(5):327-340.

- CDC (Division of Parasitic Diseases (DPDx): Laboratory Identification of Parasites of Public Health Concern. Atlanta: Center for Disease Control & Prevention, USA. Accessed [February 15, 2011].Available from: http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/Default.htm.

- Pillai DR and Kain KC. Common intestinal parasites. Current Treatment Options in Infectious Diseases 2003; 5:207-217.

- Mineno T and Avery MA. Giardiasis: Recent Progress in Chemotherapy and Drug Development (Hot Topic: Anti-Infective Agents Executive Editors: Mitchell A. Avery/Vassil St.) Georgiev. Curr Pharm Des 2003; 9(11):841-855.

- Azazy A and Raja'a Y. Malaria and intestinal parasitosis among children presenting to the paediatric centre in Sana'a, Yemen. East Mediterr Health J 2003; 9(5-6):1048-1053.

- Ak M, Keleş E, Karacasu F, Pektaş B, Akkafa F, Ozgür S, Sahinöz S, Ozçirpici B, Bozkurt AI, Sahinöz T, Saka EG, Ceylan A, Ilçin E, Acemioğlu H, Palanci Y, Gül K, Akpinar N, Jones TR and Ozcel MA. The distribution of the intestinal parasitic diseases in the Southeast Anatolian (GAP = SEAP) region of Turkey. Parasitol Res 2006; 99(2): 146-52.

- Spinelli R, Brandonisio O, Serio G, Trerotoli P, Ghezzani F, Carito V, Dajçi N, Doçi A, Picaku F and Dentico P.Intestinal parasites in healthy subjects in Albania. Eur J Epidemiol 2006; 21(2):161-166.

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Computerized information system for infectious diseaseas (CISID).Accessed [February 15, 2011]. Available from:http://data.euro.who.int/cisid/.

- Raza H and Sami R. Epidemiological study on gastrointestinal parasites among different sexes, occupations, and age groups in Sulaimani district. J Duhok Univ 2009; 12:317-323.

- 114. Sayyari AA, Imanzadeh F, Bagheri Yazdi SA, Karami H and Yaghoobi M.Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections in the Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J 2005;11(3):377–383.

- Y. Garedaghi and S. Safar Mashaei. Parasitic Infections among Restaurant Workers in Tabriz (East-Azerbaijan Province) Iran. Research Journal of Medical Sciences 2011;5(2): 116-118.

- Bobhate P, Shrivastava S and Gupta P. Profile of catering staff at a tertiary care hospital in Mumbai. Australasian Medical Journal 2011; 4(3): 148-154.

- Abera B, Biadegelgen F and Bezabih B. Prevalence of Salmonella typhi and intestinal parasites among food handlers in Bahir Dar Town, Northwest Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development 2010; 24(1):46-50.

- Wakid MH, Azhar EI and Zafar TA. Intestinal parasitic Infection among food handlers in the Holy City of Makkah during Hajj season 1428 Hegira (2007G). Journal of King Abdulaziz University Medical Sciences 2009; 16(1):39–52.

- Babiker M, Ali M and Ahmed E. Frequency of intestinal parasites among food-handlers in Khartoum, Sudan. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 2009; 15(5):1098-1104.

- Simsek Z, Koruk I, Copur AC, Gürses G. Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus and Intestinal Parasites Among Food Handlers in Sanliurfa, Southeastern Anatolia. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 2009; 15(6):518-523.

- Abu-Madi MA, Behnke JM and Ismail A. Patterns of infection with intestinal parasites in Qatar among food handlers and housemaids from different geographical regions of origin. Acta Trop 2008; 106(3):213-220.

- Baswaid SH and Al-Haddad A. Parasitic infections among restaurant workers in Mukalla (Hadhramout/Yemen). Iranian Journal of Parasitology 2008; 3(3): 37-41.

- Takizawa MGMH, Falavigna DLM and Gomes ML. Enteroparasitosis and their ethnographic relationship to food handlers in a tourist and economic center in Paraná, Southern Brazil. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo 2009; 51(1):31-35.

- DeBess EE, Pippert E, Angulo FJ and Cieslak PR. Food handler assessment in Oregon. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease 2009; 6(3):329-335.

- Mudey AB, Kesharwani N, Mudey GA, Goyal RC, Dawale AK and Wagh VV. Health Status and Personal Hygiene among Food Handlers Working at Food Establishment around a Rural Teaching Hospital in Wardha District of Maharashtra, India. Global Journal of Health Science 2010; 2(2):198-206.

- Tonder I, Lues JFR and Theron MM.The Personal and General Hygiene Practices of Food Handlers in the Delicatessen Sections of Retail Outlets in South Africa. J Environ Health 2007; 70(4):33-39.

- Bas M, Ersun AS and Kivanc G. Implementation of HACCP and prerequisite programs in food businesses in Turkey. Food control 2006; 17(2):118-126.

- Askarian M, Kabir G, Aminbaig M, Memish ZA and Jafari P. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of food service staff regarding food hygiene in Shiraz, Iran. Infection control and hospital epidemiology 2004; 25(1):16-20.

- Walker E, Pritchard C and Forsythe S. Food handlers' hygiene knowledge in small food businesses. Food Control 2003; 14(5):339-343.

- Cecilia B, Santo G, Marco G, Maurizio LG and Caterina M. Food safety in hospital: knowledge, attitudes and practices of nursing staff of two hospitals in Sicily, Italy. BMC Health Services Research 2007; 7:45-56.

- Okojie O, Wagbatsoma V and Ighoroge A. An assessment of food hygiene among food handlers in a Nigerian university campus. Niger Postgrad Med J 2005; 12(2):93-96.

- Khurana S, Taneja N, Thapar R, Sharma M and Malla N. Intestinal bacterial and parasitic infections among food handlers in a tertiary care hospital of North India. Tropical Gastroenterology 2008; 29(4):207-209.

- Udgiri R and Yadavnnavar M. Knowledge and food hygiene practices among food handlers employed in food establishments of Bijapur City. Indian J Public Health 2006; 50(4):240-241.

- Kalantan KA. Al-Faris EA and Al-Taweel AA. Pattern on intestinal parasitic infection among food handlers in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia..Saudi Society of Family and community Medicine 2001; 8(3):1-12.

- Mohan U, Mohan V and Raj K. A study of carrier state of S. Typhi, intestinal parasites & personal hygiene amongst food handlers in Amritsar city. Indian Journal of Community Medicine 2006; 31(2):60-61.

- Abahussain NA and Abahussain N. Prevalence of intestinal parasites among expatriate workers in Al-Khobar, Saudi Arabia. Middle East Journal of Family Medicine 2005; 3(3):17-21.

- 144. Al-Lahham A, Abu-Saud M and Shehabi A. Prevalence of Salmonella, Shigella and intestinal parasites in food handlers in Irbid, Jordan. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res 1990; 8(4):160-162.

- Wakid M. Distribution of intestinal parasites among food handlers in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Parasitic Diseases 2006; 30(2):146-152.

- Idowu O and Rowland S. Oral fecal parasites and personal hygiene of food handlers in Abeokuta, Nigeria. African health sciences 2006; 6(3):160-164.

- Fawzi M, Gomaa NF and Bakr W. Assessment of hand washing facilities, personal hygiene and the bacteriological quality of hand washes in some grocery and dairy shops in alexandria, egypt. J Egypt Public Health Assoc 2009; 84(1-2):71-93.

- Baş M, Şafak Ersun A and Kıvanç G. The evaluation of food hygiene knowledge, attitudes, and practices of food handlers' in food businesses in Turkey. Food Control 2006; 17(4):317-322.