Risk Factors Analysis of Childhood Asthma in Dubai, UAE

Al Behandy N. S.1, Hussein H.1, *, Al Faisal W.1, El Sawaf E.2, Wasfy A.3, Alshareef N.1, Altheeb A. A. S.1

1School and Educational Institutions Health Unit, Health Affairs Department, Primary Health Care Services Sector, Dubai Health Authority, Dubai, UAE

2Staff Development, Health Centers Department, Primary Health Care Services Sector, Dubai Health Authority, Dubai, UAE

3Statistics and Research Department, Ministry of Health, Dubai, UAE

Abstract

Background: Asthma is a large and growing threat to children’s health and well-being. It affects 5-10% of the population or an estimated 23.4 million persons, including 7 million children in U.S. Asthma is the most common chronic disease of childhood. Almost 1 in 8 school-aged children are affected by asthma, and 10% of children (compared with 5% of adults) take medication for it. Objectives: Studying Risk factors for childhood asthma in Dubai, UAE Methodology: A cross-sectional study conducted among multistage stratified randomly selected students sample in preparatory and secondary schools "Governmental and Private" in Dubai, U.A.E, The total sample size reached 1639 students. Results: parental education, crowding index and number of windows per room. It can be noted that as regards father education the highest prevalence of asthma was seen among students whose fathers were of lower education (illiterate 26.7%) as compared to those whose fathers were of university education (15.3%) with the exception of those in preparatory school (14.3%). Students whose fathers were secondary educated had a significant risk of 1.4 times more than those whose fathers were university educated and 2.1 times higher for those whose fathers were illiterate than those whose fathers were university educated. The prevalence of persistent asthma among asthmatic students was higher among the older age groups (31.3%, 26.3% and 53.8% in students of 13-<15, 15-<17 and 17+ years of age respectively) compared to those of <13 years of age (15.9%). A significant elevated risk was found among students in the 13-<15 years of age group (OR=2.4) and those of 17+ years of age group (OR=6.2). Sex, nationality and type of school revealed no statistical significant relation with severity of asthma. Conclusion: There are many risk factors playing significant role in diseases prevalence and diseases severity and clinical presentation, which needs to be well addressed to be able to modified as a part of diseases management protocol. Recommendations: Working at risk factor manipulation level through setting up long term preventive and intervention community and family based programs to modify asthma prevalence and clinical presentations.

Keywords

Childhood Asthma, Risk Factors, Dubai

Received: May 7, 2015

Accepted: May 30, 2015

Published online: August 2, 2015

@ 2015 The Authors. Published by American Institute of Science. This Open Access article is under the CC BY-NC license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

1. Introduction

Asthma is a large and growing threat to children’s health and well-being.(1) It affects 5-10% of the population or an estimated 23.4 million persons, including 7 million children in the U.S.(2) Asthma is the most common chronic disease of childhood. Almost 1 in 8 school-aged children are affected by asthma, and 10% of children (compared with 5% of adults) take medication for it.(3,4) Worldwide, an estimated 300 million people are affected by asthma. Based on the application of standardized methods to the measurement of the prevalence of asthma and wheezing illness in children and adults. It appears that the global prevalence of asthma ranges from 1-18% of the population in different countries.(5) There is a good evidence that international differences in asthma symptom prevalence have been reduced, particularly in the 13-14 age group, with decrease in prevalence in North America and Western Europe and increase prevalence in regions where prevalence was previously low. Although there was little change in the overall prevalence of current wheeze, the percentage of children reported to have had asthma increased significantly, possibly reflecting greater awareness of this condition and/or changes in diagnostic practice. The increases in asthma symptoms prevalence in Africa, Latin America and parts of Asia indicate that the global burden of asthma is continuing to rise, but the global prevalence differences are lessening.(6)

Asthma is a leading chronic illness among children and youth in the United States. In 2007, 5.6 million school-aged children and youth (5-17 years old) were reported to currently have asthma; and 2.9 million had an asthma episode or attack within the previous year. On average, in a classroom of 30 children, about 3 are likely to have asthma. (7)

In a study done in Egypt in 2009 the overall prevalence of asthma among school children was 7.7% (8% in urban areas and 7% in rural areas). (8) In a study conducted in State of Qatar, the school children aged from 6-14 year revealed a prevalence of bronchial asthma as high as 19.8 % in 2004.(9) In between 2007-2009 in Saudi Arabia (Riyadh), a study among the same age range (6-14) revealed that the prevalence of asthma among school children was 11.4% (10) while in Oman, the prevalence of asthma reached 10.5% and 20.7% in 6-7 and 13-14 years old Omani children respectively. (11)

The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that 15 million disability-adjusted life-years are lost annually due to asthma, representing 1% of the total global disease burden. Annual worldwide deaths from asthma have been estimated at 250,000 and mortality does not appear to correlate well with prevalence. There are insufficient data to fully explain the variations in prevalence within and between populations. Although from the perspective of both the patient and society the cost to control asthma seems high, the cost of not treating asthma correctly is even higher.(5)

Children with asthma are at an increased risk of experiencing asthma-related respiratory symptoms in adult life.(12)Asthma is one of the leading causes of school absenteeism. In 2003, an estimated 12.8 million school days were missed due to asthma among more than 4 million children who reported at least one asthma attack in the preceding year.(13) Low-income populations, minorities, and children living in inner cities experience more emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths due to asthma than the general population.(14)

Two old studies on 1994 and 2000 in the UAE among students aged 6-13 showed that the prevalence of asthma was 13,6 % (15) and 13 % (16) respectively. In a recent study in the UAE, in Alain area which was held between 2007- 2010 showed that the prevalence of asthma in the group aged 13-19 years was 16%, while that in the adult group 19 years and above was 12%.(17)

2. Objective

Studying risk factors of childhood asthma in Dubai, UAE.

3. Methodology

This is a cross sectional study, conducted among students in preparatory and secondary schools "Governmental and Private" in Dubai, U.A.E. Computer program EPI-Info version "6.04" was used for calculation of the minimum sample size required. According to a recent study (17) the prevalence of asthma among adolescent in the UAE was found to be 16%, using 3 % degree of precision, 95% confidence interval and 1.5% design effect, the minimum sample size required was 855. A list of schools was obtained from the knowledge and Human Development Authority. Dubai includes 183 school spread along two large districts, Bur Dubai and Diera. Bur Dubai includes 90 schools, 69 private and 21 governmental, where Diera includes 93 schools, 72 private and 21 governmental. The numbers of students in preparatory and secondary stages are 42819 and 34299 respectively. Around 20289 of them in governmental schools, while 56829 are in private schools. This gives a total of 77118 students in both regions (private and governmental). A multistage stratified random sample was used. The strata were based upon geographical districts (Bur-Dubai and Diera), type of schools (governmental or private), educational grade (7th through 12th) and sex (males and females). The number of the governmental schools was less than that of private schools (42 and 141 respectively). According to the numbers of schools, a proportional allocation technique was used to determine the required sample size. A total of 16 private schools (8 from Bur Dubai and 8 from Diera), with 4 schools of boys and 4 schools of girls for each district were randomly selected. Also, 4 governmental schools (2 from Bur Dubai and 2 from Diera), with one school for each gender from each district, were randomly selected. From each school one class was selected randomly from each educational grade. All the students in the selected classes were invited to participate in the study and all of them agreed to participate (response rate 100%). The total sample size reached 1639 students.

4. Results

Table (1) shows the parental education, crowding index and number of windows per room. It can be noted that as regards father education the highest prevalence of asthma was seen among students whose fathers were of lower education (illiterate 26.7%) as compared to those whose fathers were of university education (15.3%) with the exception of those in preparatory school (14.3%). Students whose fathers were secondary educated had a significant risk of 1.4 times more than those whose fathers were university educated and 2.1 times higher for those whose fathers were illiterate than those whose fathers were university educated. As for the mother education, it can be noted that with the exception of the illiterate group, the prevalence increased with decreased educational level of the mother however the risk was not significant. Crowding index showed no significant association with asthma. As regards the room ventilation (number of windows in the room), the prevalence was found to increase with the decrease of number of windows however this was not significant.

Table 1. Prevalence of asthma among preparatory and secondary school students according to their family and housing characteristics (Dubai, 2011).

| Characteristic | Total (1639) | Non asthmatic (1366) | Asthmatic (273) | OR (95% CI) | |||

| No. | % | No. | % | ||||

| Father’s education level | University | 1062 | 899 | 84.7 | 163 | 15.3 | 1 |

| Secondary | 321 | 257 | 80.1 | 64 | 19.9 | 1.4 (1.0- 1.9) | |

| preparatory | 133 | 114 | 85.7 | 19 | 14.3 | 0.9 (0.56- 1.5) | |

| Primary | 78 | 63 | 80.8 | 15 | 19.2 | 1.3 (0.72- 2.4) | |

| Illiterate | 45 | 33 | 73.3 | 12 | 26.7 | 2.1 (1.1- 4.0) | |

| Mother’s education level | University | 855 | 715 | 83.6 | 140 | 16.4 | 1 |

| Secondary | 424 | 358 | 84.4 | 66 | 15.6 | 1.0 (0.67- 1.3) | |

| preparatory | 127 | 102 | 80.3 | 55 | 19.7 | 1.3 (0.77- 2.0) | |

| Primary | 137 | 109 | 79.6 | 28 | 20.4 | 1.3 (0.83- 2.10 | |

| Illiterate | 96 | 82 | 85.4 | 14 | 14.6 | 0.83 (0.48- 1.6) | |

| Crowding index (person\ room) | ˂2 | 1209 | 998 | 82.5 | 211 | 17.5 | 1 |

| 2- | 412 | 353 | 85.7 | 59 | 14.3 | 0.74 (0.57- 1.1) | |

| 5+ | 18 | 15 | 83.3 | 3 | 16.7 | 0.94 (0.17- 3.4) | |

| No. of windows in room | No | 62 | 55 | 88.7 | 7 | 11.3 | 1 |

| ˃2 | 307 | 258 | 84.0 | 49 | 16.0 | 1.5 (0.63- 3.4) | |

| ≤2 | 1270 | 1053 | 82.9 | 217 | 17.1 | 1.6 (0.72- 3.6) | |

Table 2. Prevalence of asthma among preparatory and secondary school students according to their family history of asthma and obesity (Dubai, 2011).

| Family history | Total (1639) | Non Asthmatic (n=1366) | Asthmatic (n=273) | OR (95%CI) | |||

| No. | % | No. | % | ||||

| Family history of asthma | No | 1325 | 1176 | 88.8 | 149 | 11.2 | 1 |

| Yes | 314 | 190 | 60.5 | 124 | 39.5 | 5.2 (3.9-6.8) | |

| Family history of allergies | No | 1097 | 935 | 85.2 | 162 | 14.8 | 1 |

| Yes | 542 | 431 | 79.5 | 111 | 20.5 | 1.5 (1.1-1.9) | |

| Family history of obesity | No | 1293 | 1101 | 85.2 | 192 | 14.8 | 1 |

| Yes | 346 | 265 | 76.6 | 81 | 23.4 | 1.8 (1.3-2.3) | |

Table 3. Severity of asthma among asthmatic preparatory and secondary school students according to their demographic characteristics (Dubai, 2011).

| Total (273) | Intermittent (n=200) | Persistent (n=73) | OR (95%CI) | ||||

| No. | % | No. | % | ||||

| Age | 11- | 69 | 58 | 84.1 | 11 | 15.9 | 1 |

| 13- | 96 | 66 | 68.8 | 30 | 31.3 | 2.4 (1.1- 5.2) | |

| 15- | 95 | 70 | 73.7 | 25 | 26.3 | 1.9 (0.86- 4.1) | |

| 17+ | 13 | 6 | 46.2 | 7 | 53.8 | 6.2 (1.7- 21.8) | |

| Sex | Female | 123 | 93 | 75.6 | 30 | 24.4 | 1 |

| Male | 150 | 107 | 71.3 | 43 | 28.7 | 1.2 (0.72- 2.1) | |

| Nationality | Non-locals | 111 | 88 | 79.3 | 23 | 20.7 | 1 |

| Locals | 162 | 112 | 69.1 | 50 | 30.9 | 1.73 (0.98- 3.0) | |

| School type | Private | 188 | 137 | 72.9 | 51 | 27.1 | 1 |

| Governmental | 85 | 63 | 74.1 | 22 | 25.9 | 0.91 (0.53- 1.7) | |

Table 4. Severity of bronchial asthma among asthmatic preparatory and secondary school students according to their family and housing characteristics (Dubai, 2011).

| Total (273) | Intermittent (n=200) | Persistent (n=73) | OR (95%CI) | ||||

| No. | % | No. | % | ||||

| Father’s education level | University | 163 | 122 | 74.8 | 41 | 25.2 | 1 |

| Secondary | 64 | 42 | 65.6 | 22 | 34.4 | 1.6 (0.83- 2.9) | |

| preparatory | 19 | 17 | 89.5 | 2 | 10.5 | 0.35 (0.8- 1.8) | |

| Primary | 15 | 11 | 73.3 | 4 | 26.7 | 1.1 (0.33- 3.6) | |

| Illiterate | 12 | 8 | 66.7 | 4 | 33.3 | 1.5 (0.43- 5.2) | |

| Mother’s education level | University | 140 | 106 | 75.7 | 34 | 24.3 | 1 |

| Secondary | 66 | 43 | 65.2 | 23 | 34.8 | 1.7 (0.89- 3.2) | |

| preparatory | 25 | 19 | 76.0 | 6 | 24.0 | 0.99 (3.6- 2.7) | |

| Primary | 28 | 21 | 75.0 | 7 | 25.0 | 1.1 (0.41- 2.7) | |

| Illiterate | 14 | 11 | 78.6 | 3 | 21.4 | 0.85 (0.22- 3.2) | |

| Crowding index (person\ room) | ˂2 | 211 | 151 | 71.6 | 60 | 28.4 | 1 |

| 2- | 59 | 47 | 79.7 | 12 | 20.3 | 0.64 (0.32- 1.3) | |

| 5+ | 3 | 2 | 66.7 | 1 | 33.3 | 1.3 (0.11- 14.1) | |

| No. of windows in room | No | 7 | 7 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 |

| ˃2 | 49 | 34 | 69.4 | 15 | 30.6 | 6.7 (0.31- 125.6) | |

| ≤2 | 217 | 159 | 73.3 | 58 | 26.7 | 5.5 (0.31- 97.8) | |

Table (2) presents the prevalence of asthma according to the family history of asthma and obesity in Dubai 2011. The prevalence of asthma was higher among those with family history of asthma (39.5%) as compared to those with no family history (11.2%) and this yielded a significant risk of 5.2 times more among those with family history of asthma. A significant risk of developing asthma can also be noted among those with family history of allergies (1.5 times) and those with family history of obesity (1.8 times).

Table (3) shows the relationship between demographic characteristics of asthmatic students and asthma severity. The prevalence of persistent asthma among asthmatic students was higher among the older age groups (31.3%, 26.3% and 53.8% in students of 13-<15, 15-<17 and 17+ years of age respectively) compared to those of <13 years of age (15.9%). A significant elevated risk was found among students in the 13-<15 years of age group (OR=2.4) and those of 17+ years of age group (OR=6.2). Sex, nationality and type of school revealed no statistical significant relation with severity of asthma.

Table (4) shows the relationship between family and housing characteristics of asthmatic students and the asthma severity in Dubai 2011. No clear pattern of increasing or decreasing risk of persistent asthma were found with either father‟s or mother‟s educational level. There was also no evidence that crowding index was associated with risk of persistent asthma, although the prevalence of persistent asthma among those living in houses with 5 persons or more per room (33.3%) was higher compared to those living in houses with less than 2 persons per room (28.4%) or 2 to less than 5 persons/room (20.3%). The number of windows in the room was also not associated with risk of persistent asthma.

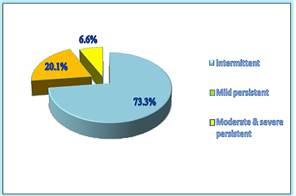

Figure (1) shows the distribution of asthmatic children according to the severity of asthma, it can be noted that 73.3% showed intermittent asthma, 20.1% were classified as mild persistent asthma and only 6.6% were considered moderate and severe persistent asthma. However due to the small sample size among moderate and severe persistent asthma they were combined to the mild persistent asthma group and thus asthmatic students were classified as with either intermittent or persistent asthma for subsequent analysis.

Figure 1. Distribution of asthmatic preparatory and secondary school students according to the severity of asthma.

5. Discussion

Our study showed that the prevalence of persistent asthma among asthmatic students was higher among the older age groups with a very high significant elevated risk among students aged 17 years and older. This is in contrast with another case control study which was conducted in Baghdad among primary school children aged 6-12 years both showed a decreasing in asthma severity by age.(18) Although Boys had higher statistically significant propensity to acquire bronchial asthma, gender revealed no difference concerning severity. Our findings go in agreement with the study done in the UAE(17) as males were significantly more often reporting asthma (17% vs. 14% among females). In another study done between ages 6-14 years old in Qatar, the prevalence of asthma and allergic rhinitis decreased with increasing age. There were statistically significant differences between sexes, males had more asthma, allergic rhinitis, and chest infections compared to females.(9) In other studies the pattern was found to be different where a female-to-male prevalence was at least 50:50.(19)

The studies done in UAE have proved that boys were more prone to get bronchial asthma in comparison with girls. (15,17) Higher exposure of males to outdoor allergens may partially explain these findings because male adolescents tend to spend most of their time outside home, as opposed to their less outgoing and often more culturally oriented female counterparts.

Emirian students and those in governmental schools were more affected with bronchial asthma. Again this was in consistence with Alain study 2009, where UAE nationality children were more affected than other nationalities.(17) In what is believed is, private schools are usually more careful in keeping the maintenance processes of the air conditioning systems and cleaning procedures of the classrooms and school environments, consequently keeping what is known as "Bronchial Asthma Friendly School Environment". Besides, locals usually prefer attaching their children to governmental schools. Some parameters of socio-demographic characteristics were studied in relation to the development of bronchial asthma. Parent’s education inconsistently seemed to affect the prevalence of bronchial asthma among their children. Although apparently higher among low educated mothers, illiterate fathers had statistically significant higher percentage of asthmatic children. More than half of the study students had parents with university degrees. This goes in consistence with another study done among children aged 6-7 years in Rome which showed that the prevalence of physician diagnosis of asthma increased as father’s education decreased and the prevalence of severe asthma increased as both maternal and paternal educational levels decreased and lifetime hospitalization for asthma was strongly associated with both parental education. (20) In parallel again with the case control study which was done in Iraq between years 2000- 2002, which gave evidence that a low level of education among parents acted as a significant risk factor for development of asthma. (18) This finding was also supported by many other studies as those done in Brazil, Turkey and Sri Lanka.(21-23) With less educated families, there are adverse environmental factors such as tobacco smoking, crowding, bad nutrition and housing conditions. These factors will make children of less educated mothers and fathers more susceptible to aeroallergen in addition to less medical care.(18) Concerning living conditions, there are doubts that highly likely they can affect the health status of people. Barker et al., (2002) (24) stated that although living conditions in adult life do not seem to be important, the reverse is true regarding children and young adults. In this study crowding index showed no significant association with development of bronchial asthma among the study students. Although non-significant, the prevalence of persistent asthma was higher among those living in houses with 5 persons or more per room in comparison with those living in houses with less than 2 persons and less than five persons per room.

A case-control study in Iraq found that the crowding rate of >5 person was a significant risk factor for asthma development. (18)In our study, more than 70% of the study students were found to have homes with low crowding index.

As regards the room ventilation expressed by the number of windows in the room, the prevalence was found to increase with the decrease of number of windows, however this was not significant. In this study no clear relation could be detected between room ventilation and severity of bronchial asthma. These findings can simply be explained by the fact that Dubai is a very hot country during almost all the year with consequent total dependence of the people on air conditioning system. People cannot rely on windows as a source of natural ventilation due to the very hot and humid natural air.

On the other hand, a case-control study which included 120 cases of asthmatic children and a doubled number of controls proved that absence of windows in living rooms was among factors associated with presence of symptoms of asthma.(25)

Although family history of asthma; allergies and obesity was not statistically significantly associated with asthma severity it was found that prevalence of asthma was higher among children with family history of bronchial asthma also it was among the factors that expressed a significant effect on developing bronchial asthma among children with around five times risk. A significant risk of developing asthma was elucidated among students with family history of asthma, allergies and obesity. About 19% of the study students had positive family history of asthma with almost one third of them recorded family history of different types of allergic disorders. This goes in agreement with Alain study (17) as the family history of asthma was the strongest predictor of asthma. Another study in Iraq showed positive association between family history and asthma whether among father, or mother or sibling.(18) Again those finding are in consistent with many other studies elsewhere in the world.(21,26,27) The association between the risk of getting bronchial asthma and family history of obesity can be explained as both conditions caused by shared genetic risk factors. (28)

The relation between bronchial asthma and weight of the study students was also investigated. Based on the results of stepwise logistic regression analysis, obesity was an important contributing factor abreast with other factors that were significantly related to the prevalence of asthma namely family history of asthma and being a governmental school student.

In this study according to percentile classification it was shown that, 16% of the study students were overweight while 12.8% were obese. Overweight and obese students were found to have almost doubled risk of developing asthma compared with those who are normal/underweight. Body mass index percentile classification proved that in comparison with normal/underweight students, their overweight and obese male and female counterparts had higher risk of developing bronchial asthma. On the other hand BMI revealed no relation with everity of asthma in this study. The relationship between body mass index percentiles classification and asthma symptoms among asthmatic students was clear. It can be noted that the percentage of asthmatic students with current wheezing (wheezes in the last 12 months) increased with increasing level of obesity (68.9%, 78% and 82.4% in normal/underweight, overweight and obese students respectively), however it was found to be statistically insignificant. On the other hand, body weight revealed a statistical significant relation with some trends of asthmatic attacks. Those who had more than four attacks of wheeze within the last 12 months were more prevalent among overweight than obese students respectively in comparison to normal weight students. Same finding was found regards the frequency of asthma symptoms where it was found that the more the weight of the student the more the frequency of asthma attacks, the differences were statistically significant. Sleeping disturbances or speech limitation due to wheezing, and frequency of nocturnal symptoms, wheezing during or after exercise and rate of inhaler use were all apparently higher among obese and overweight asthmatic children.

6. Conclusion

There are many risk factors playing significant role in diseases prevalence and diseases severity and clinical presentation, which needs to be well addressed to be able to be modified as a part of diseases management protocol.

Recommendation

Working at risk factor manipulation level through setting up long term preventive and intervention community and family based programs to modify asthma prevalence and clinical presentations.

References

- National Asthma Education and Prevention Program: Expert panel report III: Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. Bethesda: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 2007. [Cited on January 30, 2011]. Available from: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.htm.

- Tarlo SM, Balmes J, Balkissoon R, Beach J, Beckett W, Bernstein D, Blanc PD, Brooks SM, Cowl CT, Daroowalla F, Harber P, Lemiere C, Liss GM, Pacheco KA, Redlich CA, Rowe B, Heitzer J. Diagnosis and management of work-related asthma: American College Of Chest Physicians Consensus Statement. Chest 2008 Sep;134 (3 Suppl):1S-41S.

- Data from National Health Review Survey. National Center For Health Statistics. U.S. Department Of Health and Human Services. Center For Disease Control and Prevention 2006. [Cited on 10/12/2010]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/asthma/NHIS/06/Data.htm

- Health 4 Kids. Health Canada 2008. [Cited on January 7, 2011]. Available from: http:www.hc-sc.gc.ca/english/for_you/health4kids/body/asthma.htm.

- Bateman ED, Hurd SS, Barnes PJ, Bousquet J, Drazen JM, FitzGerald MM, Gibson P, Ohta K, O‟Byrne P. Pedersen SE, Pizzichini E, Sullivan SD, Wenzel SE, Zar HJ. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention: GINA executive summary. Eur Respir J 2008 Jan;31(1):143-78.

- Pearce N, Aït-Khaled N, Beasley R, Mallol J, Keil U, Mitchell E, Robertson C. Worldwide trends in the prevalence of asthma symptoms: phase III of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC). Thorax 2007 Sep; 62(9): 758-66.

- American Lung Association, Epidemiology and Statistics Unit, Research and Program Services. Trends in Asthma Morbidity and Mortality 2009. [Cited on January 20, 2011]. Available from: http://www.lungusa.org/finding-cures/our-research/trend-reports/asthma-trendreport. pdf

- Zedan M, Settin A, Farag M, Ezz-Elregal M, Osman E, Fouda A. Prevalence of bronchial asthma among Egyptian school children, Egyptian Journal of Bronchology 2009 Dec; 3(2):124-130.

- Janahi IA, Bener A, Bush A. Prevalence of Asthma Among Qatari Schoolchildren: International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood, Qatar, Pediatr Pulmonol 2006 Jan;41(1):80-6.

- Harfi H, AlAbbad K, Alsaeed AH. Decreased Prevalence of Allergic Rhinitis, Asthma and Eczema in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia, Trends in Medical Research 2010;5(2): 57-62.

- Al-Riyami BM, Al-Rawas OA, Al-Riyami AA, Jasim LG, Mohammed AJ. A relatively high prevalence and severity of asthma, allergic rhinitis and atopic eczema in schoolchildren in the Sultanate of Oman. Respirology 2003 Mar;8(1):69-76.

- Sears MR, Greene JM, Willan AR, Wiecek EM, Taylor DR, Flannery EM, Cowan JO, Herbison GP, Silva PA, Poulton R. A longitudinal, population-based, cohort study of childhood asthma followed to adulthood. N Engl J Med 2003 Oct 9;349(15):1414-22.

- Akinbami LJ. The State of Childhood Asthma, United States, 1980-2005. Adv Data 2006 Dec; 12(381):1-24.

- Lieu TA, Lozano P, Finkelstein JA, Chi FW, Jensvold NG, Capra AM, Quesenberry CP, Selby JV, Farber HJ. Racial/Ethnic Variation in Asthma Status and Management Practices Among Children in Managed Medicaid. Pediatrics 2002 May; 109(5): 857-65.

- Bener A, Abdulrazzaq YM, Debuse P, Al-Mutawwa J. Prevalence of asthma among Emirates school children. Eur J Epidemiol 1994 Jun;10(3):271-8.

- Al-Maskari F, Bener A, al-Kaabi A, al-Suwaidi N, Norman N, Brebner J. Asthma and respiratory symptoms among school children in United Arab Emirates. Allerg Immunol (Paris) 2000 Apr; 32(4): 159-63.

- Alsowaidi S, Adulle A, Bernsen R. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Asthma among Adolescents and Their Parents in Al-Ain (United Arab Emirates). Respiration 2010; 79(2):105-11.

- Al-Kubaisy W, Ali SH, Al-Thamiri D. Risk factors for asthma among primary school children in Baghdad, Iraq. Saudi Med J 2005 Mar;26(3):460-6.

- Almqvist C, Worm M, Leynaert B. Gender: Impact of gender on asthma in childhood and adolescence: a GA2LEN review. Allergy 2008 Jan;63(1):47-57.

- Cesaroni G, Farchi S, Davoli M, Forastiere F, Perucci CA. Individual and area-based indicators of socioeconomic status and childhood asthma. Eur Respir J 2003 Oct;22(4):619-24.

- Chatkin MN, Menezes AM, Victora CG, Barros FC. High prevalence of asthma in preschool children in southern Brazil: a population-based study. Pediatr Pulmonol 2003 Apr; 35(4): 296-301.

- Ece A, Ceylan A, Saraclar Y, Saka G, Gürkan F, Haspolat K. Prevalence of asthma and other allergic disorders among schoolchildren in Diyarbakir, Turkey. Turk J Pediatr 2001 Oct- Dec;43(4):286-92.

- Karunasekera KA, Jayasinghe JA, Alwis LW. Risk factors of childhood asthma: a Sri Lanka study. J Trop Pediatr 2001 Jun; 47(3): 142-5.

- Economist Intelligence Unit Quality of Life Index: UAE ranks number one in Mena, (The Ultimate Middle East Business Resource). [Cited 2011 Feb 29]. Available from: http://www.AMEinf.com

- Pokharel PK, Bhatta NK, Pandey RM, Erkki K. Asthma symptomatics school children of Sonapur. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2007 Oct-Dec;5(4):484-7.

- Liebhart J, Malolepszy J, Wojtyniak B, Pisiewicz K, Plusa T, Gladysz U. Polish Multicentre Study of Epidemiology of Allergic Diseases: Prevalence and risk factors for asthma in Poland: results from the PMSEAD study. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2007;17(6):367-74.

- Burke W, Fesinmeyer M, Reed K, Hampson L, Carlsten C. Family history as a predictor of asthma risk. Am J Prev Med 2003 Feb;24(2):160-9.

- Hallstrand TS, Fischer ME, Wurfel MM, Afari N, Buchwald D, Goldberg J. Genetic pleiotropy between asthma and obesity in a community-based sample of twins. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005 Dec; 116(6):1235-41.