Nurses and Midwives Compliance with Standard Precautions in Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital, Sagamu Ogun State

Ojewole Foluso*, Ibezim Sandra Makuochi

School of Nursing, Adult Health Department, Babcock University Ilishan, Ogun State, Nigeria

Abstract

Compliance refers to the extent to which health care workers follow the rules, regulations and recommendations of Standard Precautions (SP) and Infection Control (IC). The widespread inability of health care workers in developing countries to implement SP necessary for protecting themselves frequently has devastating consequences. Therefore, this study examined nurses and midwives compliance with standard precautions in Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital (OOUTH). A descriptive survey research design was used for the study. The population consisted of all nurses and midwives in the selected health center. 154 nurses and midwives were randomly selected for the study. The outcomes of this study revealed that 96.1% of the respondents complied to hand hygiene and use of personal protective equipments (PPE), while personal (53.7%) and institutional (81.6%) factors were found to influence the practice of standard precautions among nurses and midwives. Also, 79.8 percent of the nurses and midwives adhered strictly to the use of the standard precautions of hand washing. The study further revealed a significant association between compliance with standard precautions and availability of PPE (r = .195, p = .017). The findings further revealed no significant association between compliance with standard precautions and nurses years of experience (r = .048, p = .017). It was concluded that nurses as the forefront professional in the healthcare systems are responsible for controlling nosocomial infection through adequate practice. Therefore, regular education and training programs for nurses and midwives on compliance with standard precaution should be organized in the hospitals and school of nursing within Ogun State. Hospital policy and procedures should address the need for nurses to observe standard precautions on all patients, regardless of knowledge about their infection status, Lastly hospital management should ensure the adequate provision of standard PPE materials necessary for compliance with SP.

Keywords

Nurses, Midwives, Compliance Level, Standard Precautions, Health Status

Received: April 30, 2015

Accepted: June 8, 2015

Published online: July 15, 2015

@ 2015 The Authors. Published by American Institute of Science. This Open Access article is under the CC BY-NC license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

1. Introduction

Standard precautions is defined by the Center for Diseases Control (CDC) (2007) as a set of precaution or actions designed to prevent the transmission of human immuno deficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus and blood borne pathogens through exposure to blood and body fluid when providing first aid or health care . The term standard precaution connotes that any body fluid may contain contagious and harm micro organisms. The practice of standard precaution applies the basic principles of infection control through hand hygiene, use of personal protective equipments (PPE) such as gloves, gowns, goggles, masks, handling and disposal of sharp instruments and waste to prevent direct contact from pathogen from either patient or nurse thus reducing the risk of cross infection.

Nurses and midwives are directly involved in patient care and are, therefore, more prone to acquiring infections from patients especially blood borne diseases including HCV, HBV, and HIV / AIDS. It has been estimated worldwide that more than 170 million people are infected with Hepatitis C and about 40 million are living with HlV / AIDS (Richmond & Dunning 2007). There is enough evidence showing that proper compliance with Standard Precautions (SP) can protect health care workers from various kinds of Occupational Blood Exposure (OBE), Hospital Acquired Infections (HAP) including pneumonia and intravascular catheter infections (Tetali & Choudhry 2006)

Evidence suggests that nurses and midwives do not consistently adopt protective barriers and thus they become more prone to contracting blood related diseases (Eggimann, 2007). One report indicated that because of the fear of contracting HIV / AIDS nurses were inclined to give up their profession. They also expressed the need to be informed about the HIV status of the patients and demanded that the HIV testing for all patients should be mandatory (Jaun, 2004). Nurses need to protect themselves against such infections and this is possible only when they comply with the set guidelines of Standard precautions. In Nigeria, there is paucity of data related to nurses’ compliance with Standard precautions.

The National Health and Medical Research Council and the National Council on Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome recommended a 2-tiered approach to infection control (National Health and Medical Research Council, 1996). The World Health Organization (WHO, 2004) refers to the first tier as ‘standard precautions, which are the first line of defense in infection control. It includes diligent hygiene practices (hand hygiene and drying), use of protective clothing, appropriate handling and disposal of sharps, prevention of needle stick or sharp injuries, appropriate handling of patient care equipment and soiled linen, environmental cleaning and spills management, appropriate handling of waste as well as protective clothing such as gloves, gowns, aprons, masks and protective eyewear.

The second tier of precautions are strategies such as quarantine that is used in addition to standard precautions in situations in which standard precautions may be insufficient to prevent transmission of infection. Furthermore, The Centre for Disease Control (CDC) in the United States formulated the basic elements of standard precautions in the 1980s which undergoes revision till date (Jeong, Cho, & Park, 2008), and these have since been adapted for use in other countries. According to the South African version, the four basic elements of standard precautions that should be implemented in all health care settings include that all body fluids should be handled with the same precautions as blood, the avoidance of sharps (sharp objects); avoidance of skin or mucous membrane contamination; and cleaning/disinfection/sterilizing of equipment contaminated by blood or body fluids (Committee for Science & Education, MASA, 2005).

The reasons for non-compliance to universal precaution include lack of knowledge, interference with working skills, risk perception, conflict of interest, not wanting to offend patients, lack of equipment and time, uncomfortable protective clothing, inconvenience, work stress, and a weak organizational commitment to safety climate (Kermode 2005). He further noted that the protection of nurses and midwives is neglected in low and middle-income countries, even though they might be at higher risks than colleagues in higher-income countries, because of high disease prevalence among the patient population.

Against the background of the high occurrence of HIV/AIDS, Nurses/ Midwives and patients in operating theatres are at particularly high risk of exposure to occupational hazards and infections from blood and body fluid. In view of this, this study will be looking at the Nurses and Midwives compliance to Standard Precaution in a government owned hospital in Ogun State.

2. Statement of the Problem

Proper clinical application of standard precaution is very important for every health care professional, it has been observed that standard precautions are not practiced fully by nurses and midwives in some hospitals before, during and after contact with patient as most nurses recap needles after use, rarely wear gloves during sterile procedures like wound dressing and can hardly differentiate wastes. Research indicates that the use of standard precautions significantly decreases the number of incidents of occupation exposure to blood and body fluids (Wilson 2006). Although standard precautions have been practiced for a long time, full compliance has been difficult to achieve. Though, a number of studies on health care workers’ (nurses and midwives) knowledge and compliance to standard precautions SP have been done in Nigeria (Okeke, 2009; Adeniran, Wilson & Ayebo, 2006), yet there is need to conduct more research on the subject matter. This unwholesome practice is harmful to the health of the nurses and midwives and there is still a dearth in research on the knowledge and compliance with universal or standard precautions among nurses in most hospitals in Nigeria. It is against this background that this study examined the level of compliance with standard precaution, as well as factors affecting and promoting compliance among nurses and midwives working in Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital, Sagamu, Ogun State.

3. Research Questions

The following questions were asked from the nurses and midwives working in the selected hospital.

1. What the factors that influence the practice of standard precautions among nurses and midwives?

2. What are the level of compliance with standard precaution specifically hand hygiene and use of PPE among the nurses and midwives?

3. What type of standard precautions do the nurses and midwives practice?

4. Research Hypotheses

1. There is an association between availability of PPE and compliance with standard precautions.

2. There is an association between nurses’ years of experience and compliance to standard precaution.

5. Research Methodology

Research design: This study employed a survey research design of an ex-post – facto type in which the existing status of the independent variables were only determined during data collection without any manipulation of the variables by the researcher.

Research setting: Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching hospital is a tertiary health institution located in Sagamu Ogun State. It is a 300-bed hospital established on 1st of January, 1986 comprising of a total number of 405 staff. Among these, 250 were nurses and midwives. The clinics include eye clinic, ear nose and throat clinic, virology, ante-natal, child survival clinic, children out patient department, general out-patient department, and consultant out-patient department.

Target population: Nurses and midwives working in the clinical settings (wards) with the exclusion of those working in the administrative or non-clinical settings were the target population for this study.

Sample size and Sampling technique: The simple random sampling method was used to select the number of nurses and midwives that were present on a particular shift and clinic day. The total number of nurses and midwives working in OOUTH as at the time of this study are 250 and the sample size was selected using Taro Yamane’s formula.

Total number of nurses working in OOUTH = 250

Estimated target population (N) = 250

N = 250 nurses and midwives

Using Yamane’s formulae;

![]()

Where n = sampling size,

N =estimated target population,

e =any sampling error

At 95% confident level and 5% precision level, N-100, e=0.05, n= 80

n= 250/1+250 (0.05)2

n=250/1 + 250 (0.0025)

n= 250/ 1 + 0.625

n= 250/ 1.625

n= 153.84

Therefore, the sample size is 154.

Instrument used for data collection: A self-constructed questionnaire based on 4-point Likert type was used to gather data from the participants in the study. The questionnaire tagged "Nurses and Midwives Compliance with Standard Precautions Questionnaire (NMCSQ). The questionnaire is comprised of three sections with a total number of 30 questions which include Section A: Demographic data, Section B compliance to universal precaution, Section C factors influencing compliance with universal precaution. Section B and C were measured on a 4 likert scale format with response ranging from Strongly Disagree (1), Disagree (2), Agree (3) to Strongly Agree (4).

Validity and Reliability of Instruments: In developing the questionnaire, all necessary variables of the study were incorporated into the instrument. The instrument was subjected to criticism and moderation from test construction experts. The criticism and moderation or adjustment helped in eliminating inadequate and invalid items thereby establishing content validity of the instrument. To test the reliability of the instrument, the researcher administered the instrument to 10 nurses and 10 midwives from Babcock University Teaching Hospital. This constitutes the pilot study group. A after a period of two weeks, the same instrument was re-administered to the same respondents to determine its reliability. The instrument had reliability co-efficient of 0.81.

Procedure for Data collection: The researcher obtained a letter of permission from the School of Nursing, Babcock University which was used to gain consent and permission from the director of nursing services from both hospitals to share the questionnaire so as to enhance cooperation with the nurses and midwives. The purpose of the study was also explained to the nurses and midwives to encourage their involvement in the study and also to obtain their consent. The questionnaire was personally administered to the participants (nurses and midwives).

Method of Data Analysis: The responses made from the data collected from questionnaire were analyzed and processed with the aid of pearson product moment correlation coefficient (PPMC) and percentage analysis of the 21st version of Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS). The PPMC test was used to find the association between variables.

Ethical Consideration: An ethical clearance was obtained from the ethical committee of OOUTH. Prospective subjects were fully informed about the nature of the study and that their participation was voluntary. Firstly, we have used anonymity as a tool to avoid harming participants in any way. The respondents’ names, positions, and departments were not stated publicly, so that the respondents could have spoken freely. Our main agenda was to make respondents unidentifiable. Secondly, we have given our respondents all the information that was important. For example, we have stated our research purpose, and the way in which data will be handled. Thirdly, we have posed our questions in such a way that would avoid invading personal space of the respondents. Moreover, pursuant to Bryman and Bell’s suggestion (2011), the respondents had a right to refuse answering any question for any reason they felt. Finally, we have been very clear and precise about the purpose of our research in order to avoid any deception. Deception is a word used to describe a situation when the research is represented as something that it is not (Bryman & Bell, 2011).

Table 1. Participants’ Socio-demographic characteristics.

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage | ||

| 1 | Gender | Male | 29 | 19.6 |

| Female | 119 | 80.4 | ||

| 2 | Age | 30yrs below | 73 | 49.3 |

| 31-40yrs | 49 | 33.1 | ||

| 41-50yrs | 24 | 16.2 | ||

| 50yrs above | 2 | 1.4 | ||

| 3 | Years of working experience | Less than 5yrs | 50 | 33.8 |

| 6-10years | 63 | 42.6 | ||

| 11-20years | 32 | 21.6 | ||

| 21years above | 3 | 2.0 |

N = 148

6. Results and Discussions

Participants’ demographic results revealed that majority of the nurses and midwives were below the age of 30years representing 49.3% of the sampled population, 33.1% were between 31-40 years, while 16.2% were between 41-49years and 1.4% were 50 years above. Regarding their gender, majority of the respondents were female nurses and midwives (80.4%) while the rest 19.6% were male. 42.6% had worked between 6-10 years while 40.5% were Registered Nurse and Registered Midwives.

Table 2. Compliance with Universal Precaution (SP).

| Compliance | SA (%) | A (%) | D (%) | SD (%) | |

| 1 | wears disposable gloves during procedures | 123 (83.1) | 21 (14.2) | 3 (2.0) | 1 (.7) |

| 2 | washes hands after removal of gloves | 123 (83.1) | 23 (15.5) | 2 (1.4) | - |

| 3 | discards gloves after care of a single patient | 113 (76.4) | 28 (18.9) | 7 (4.7) | - |

| 4 | wears facemask whenever there is a possibility of splash or splatter | 116 (78.4) | 28 (18.9) | 3 (2.0) | 1 (.7) |

| 5 | disposes all used sharp objects into the sharp boxes | 122 (82.4) | 24 (16.2) | 2 (1.4) | - |

| 6 | separates all waste and dispose according to category | 100 (67.6) | 42 (28.4) | 4 (2.7) | 2 (1.4) |

| 7 | treats all patients and materials as if they were infectious | 114 (77.0) | 27 (18.2) | 7 (4.7) | - |

| 8 | promptly wipes up all potentially contaminated spills using disinfectant | 95 (64.2) | 38 (25.7) | 7 (4.7) | 8 (5.4) |

| Weighted Average Scores | 76.5% | 19.5% | 3.0% | .9% |

Options: SA = Strongly Agree, A = Agree, D = Disagree, SD = Strongly Disagree.

96.1% agreed (strongly agreed and agreed), 3.9% disagreed (strongly disagreed and disagreed).

Table 3. Factors Influencing Choice of Standard Precaution.

| Individual Factors | SA (%) | A (%) | D (%) | SD (%) | |

| 1 | My duties interferes with my being able to follow standard precautions | 27 (18.2) | 18 (12.2) | 22 (14.9) | 81 (54.7) |

| 2 | I have enough time to always follow standard precautions | 70 (47.3) | 35 (23.6) | 21 (14.2) | 22 (14.9) |

| 3 | I develop a reaction to gloves | 23 (15.5) | 12 (8.1) | 24 (16.2) | 89 (60.1) |

| 4 | My education and training prepared me to practice SP | 116 (78.4) | 20 (13.5) | 6 (4.1) | 6 (4.1) |

| 5 | My senior colleagues practices it | 78 (52.7) | 38 (25.7) | 16 (10.8) | 16 (10.8) |

| 6 | My past experience with bloody exposure prevents me from practicing SP | 21 (14.2) | 19 (12.8) | 18 (12.2) | 90 (60.8) |

| Weighted Average Scores | 37.7% | 16.0% | 12.1% | 34.2% |

53.7% agreed (strongly agreed and agreed), 46.3% disagreed (strongly disagreed and disagreed

Table 2 above describes the compliance of nurses and midwives to SP. Findings revealed that majority 97.3% of the respondents agreed that they wear disposable gloves during procedures such as wound dressing and bed making. It was evident that 98.6% of the respondents agreed that they wash their hands after removal of gloves, 95.3% agreed they discard gloves after care of a single patient while 97.3% agreed that they wear facemask whenever there is a possibility of splash or splatter. Furthermore, it was discovered that 98.6% of the respondents agreed that they disposed all used sharp objects into the sharp boxes, 96% of the respondents agree they separated all waste and disposed according to category, 95.2% treated all patients and materials as if they were infectious, while 89.9% agreed they promptly wiped up all potentially contained spills using disinfectant. It implies that there is a high rate of nurses and midwives compliance practice towards standard precaution.

Table 3 discusses issues that affect the choice of maintaining standard precaution by nurses and midwives in OOUTH. Result revealed that 30.4% of the respondents agreed that their duties interfere with their ability to follow standard precautions while 69.9% disagreed. It implies that the duties of most nurses and midwives do not affect their choice of standard precaution. Majority of the respondents (70.9%) agreed that they had enough time to always follow standard precaution, while 29.1% do not agree, 23.6% reacts to gloves while 76.3% do not. It implies that personal reaction to gloves can highly influence choice of standard precaution. Furthermore, 91.9% of the respondents strongly agreed that their education and training prepared them to practice standard precaution, 78.4% agreed that their senior colleagues practice standard precaution, 27% agreed that past experience with bloody exposure prevents them from practicing standard precaution. It implies that past experience with exposure of blood and related issues does not affect their choice of standard precaution.

Table 4. Institutional Factors.

| Institutional Factors | SA (%) | A (%) | D (%) | SD (%) | |

| 1 | I am provided with all necessary equipment to comply with SP | 65 (43.9) | 40 (27.0) | 24 (16.2) | 19 (12.8) |

| 2 | My ward is adequately staffed | 42 (28.4) | 75 (50.7) | 17 (11.5) | 14 (9.5) |

| 3 | My senior colleague often discusses safe work practices which include standard precaution with me | 76 (51.4) | 61 (41.2) | 9 (6.1) | 2 (1.4) |

| 4 | In my ward, unsafe work practices are corrected by the supervisors | 89 (60.1) | 53 (35.8) | 5 (3.4) | 1 (.7) |

| 5 | I received training organized by the institution on standard precautions or other infection control measures in the past 12 months. | 71 (48.0) | 61 (41.2) | 15 (10.1) | 1(.7) |

| 6 | The hospital policy and procedure that address the use of PPE is available. | 57 (38.5) | 67 (45.3) | 9 (6.1) | 15 (10.1) |

| 7 | The PPE materials available are of low quality | 36 (24.3) | 46 (31.1) | 27 (18.2) | 39 (26.4) |

| 8 | On my ward, nurses are encouraged to become involved in safety and health matters. | 55 (37.2) | 76 (51.4) | 7 (4.7) | 10 (6.8) |

| 9 | The ward is not crowded. | 57 (38.5) | 60 (40.5) | 15 (10.1) | 16 (10.9) |

| Weighted Average Scores | 41.1% | 40.5% | 9.6% | 8.8% |

Options: SA = Strongly Agree, A = Agree, D = Disagree, SD = Strongly Disagree

Table 5. Hand Washing Observational Monitor Check List.

| SN | Criteria | Yes (%) | No (%) | NA (%) |

| 1 | Washes hands before patients contact | 57 (75.0) | 19 (25) | - |

| 2 | Washes hands after direct contact with patients | 76 (100.0) | - | - |

| 3 | washes hand before procedures | 52 (68.4) | 24 (31.6) | - |

| 4 | Washes hands after procedures such as bed making, dressing changes etc. | 74 (97.4) | 2 (2.6) | - |

| 5 | Washes hands after direct contact with patients materials contaminated with secretions such as blood, faces or urine | 76 (100) | - | - |

| 6 | Washes hands after glove removal | 37(48.7) | 39 (51.3) | - |

| Hand Washing Methodology | ||||

| 7 | Wets both hands and use soap | 75 (98.7) | 1(1.3) | - |

| 8 | Scrubs hands for a minimum of 10 seconds using friction | 70 (92.1) | 6(7.9) | - |

| 9 | Rinse hands well under running water | 36 (47.4) | 40(52.6) | - |

| 10 | Dry hands with towel | 53 (69.7) | 14 (18.4) | 9 (11.8) |

| Weighted Average Scores | 79.8% | 19.1% | 1.1% |

This table presents the criteria used by the researcher to determine the hand washing observation of nurses on the standard precaution face-to-face while the nurses were on duty

Table 4 presents other factors that majorly influence personal choice of nurses and midwives on standard precaution. Findings revealed that 70.9% of the respondents agreed that they were provided with all necessary equipment to comply with standard precaution. However, 79.1% of the respondents agreed the ward is adequately staffed, 92.6% of the respondents agreed that their senior colleagues often discuss safe work practices which include standard precaution with them, while 89.2% of the respondents agreed that they received training organized by the institution on standard precautions or other infection control measures in the past 12 months. Finding shows that 83.8% of the respondents strongly agreed that the hospital policy and procedure addresses the use of PPE is available. On the other hand, 55.4% of the respondents agreed that PPE materials available at the hospital are of low quality. Thus, the quality of available PPE materials encourages the choice of its usage by the staff of the hospital. Survey result shows that 88.6% of the respondents agreed that they are encouraged to become involved in safety and health matters while 79% agreed that the ward is not crowded.

Finding reveals that 75% of the respondents wash their hands before patients contact, 100% of the respondents wash hands after direct contact with patients, 68.4% of the respondents wash hands before procedure, while 97.4% of the respondents wash their hands after procedures such as bed making and dressing changes. Meanwhile 100% of the respondents wash their hands after direct contact with patients’ materials contaminated with secretions such as blood, faces or urine. Also, 51.3% of the respondents do not wash their hands after glove removal while 48.7% do observed it. Based on hand washing methodology, 98.7% of the respondents wet both hands and use soap, 92.1% of the respondents scrub hands for a minimum of 10 seconds using friction, 47.4% of the respondents rinse their hands very well under running water after attending to patients while 69.7% of the respondents dry hands with towel after hand washing.

Table 6. Association between availability of PPE and compliance with standard precautions using PPMC.

| Compliance | PPE Availability | ||

| Compliance | Pearson Correlation | 1 | .195* |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .017 | ||

| N | 148 | 148 | |

| PPE Availability | Pearson Correlation | .195* | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .017 | ||

| N | 148 | 148 | |

| *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). | |||

Table 7. Association between nurses’ years of experience and compliance with PPE.

| Compliance | Working experience | ||

| Compliance | Pearson Correlation | 1 | .048 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .073 | ||

| N | 148 | 148 | |

| Working experience | Pearson Correlation | .048 | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .073 | ||

| N | 148 | 148 |

The outcome of this finding as shown in Table 6 above revealed a significant association between compliance with standard precautions and availability of PPE (r = .195, p = .017). Thus, the earlier stated hypothesis of no association between availability of PPE and compliance with standard precautions was rejected. It could then be deduced that adequate compliance with standard precautions at work was as result of availability of personal protective equipment at the hospitals.

Table 7 revealed no significant association between compliance with standard precautions and nurses years of experience (r = .048, p = .073). Therefore, the earlier stated hypothesis was rejected.

7. Discussion of Findings

The outcome of this study on the level of compliance with standard precaution specifically hand hygiene and use of PPE among the nurses and midwives showed that 96.1% of the respondents complied to hand hygiene and use of PPE. It could be said from this result that the level of compliance with standard precaution is high. The implication of this finding is that compliance with standard precautions in health centres and hospitals cannot be completely separated from work climate. The present finding is in line with the work of Kermode (2005) which discovered that promotion of safety climate often time leads to compliance to standard precaution. Also, Osborne, (2003) supports the present finding when he reported that wearing of sterile surgical gloves by health workers is very conducive for the patient and for the protecting against occupational risk caused by blood borne infections from patients as well as cross-infection. The finding of this study is different from Gammon and Gould (2005) where it was discovered in London that compliant rate of standard precaution by nurses is less than 38%. Philips (2007) states that the need to change facemasks often when wet or soiled with blood between patients is crucial.

Personal (53.7%) and institutional (81.6) factors were found to influence the practice of standard precautions among nurses and midwives. This finding implies that personal and institutional factors to a great extent determine nurses and midwives’ health status. The study’s finding is not completely different from Friedman and Bernstein, (2003) which states that health care workers inability to implement standard precaution like wearing of visor in operating theatre often time affect them greatly hence the need for full compliance to SP in health care settings.

It was observed from the findings that 79.8 percent of the nurses and midwives adhered strictly to the use of the standard precautions of hand washing. The implication of this finding is that the use of the standard precautions of hand washing is well established in the clinical and hospital settings. This is in tandem with the previous findings of Aniebue, Aguwa and Obi (2008) that compliance on the part of healthcare workers with standard precautions has been recognized as an efficient means to prevent and control health care-associated infections in patients and health workers.

Another outcome of this study revealed an association between availability of personal protective equipments (PPE) and compliance with standard precautions. It could then be deduced that adequate compliance with standard precautions at work was as result of availability of personal protective equipment at the hospitals. This might be a reason why Tokuda et al., (2009) reported that a large number of doctors leave the hospital due to poor working condition as a reason among others.

Lastly, the outcome of this study revealed no significant association between compliance with standard precautions and nurses years of experience. It could then be deduced that adequate compliance with standard precautions at work cannot be determined by the nurses’ years of experience in the clinical setting. Abdulraheem et al. (2012) supports this finding when he stated that regardless of the nurses’ years of experience their behaviour towards compliance with SP differs and also even with those with 10 years of experience had revealed lower level of compliance.

8. Conclusion

The practice of standard precaution by nurses and midwives cannot be neglected as it has proved to be of great importance to the survival and sustenance of the health lifestyle of nurses as they are susceptible to different infection and diseases when precautious measures are not properly followed in the process of treating patients or discharging their daily duties. Compliance with standard precaution like washing of hands before and after wound dressing and at contact with patient should be strictly adhered to, face and head mask ensures that health care workers who get into contact with blood or body fluid should exercise precaution to avoid skin infection and diseases through blood contacts of ill patients.

However, the contribution made by this research work will be more appreciated if the recommendations herein were adhered to for further of healthy practices at work. There is need for health professional and health organizations across the sector to address means of enhancing compliance with standard precaution by nurses and midwives from the findings of the study, the following recommendations were made by the researcher as follows:

• Regular education and training programs on compliance with standard precaution should be organized in the hospitals and school of nursing within Ogun State for early understanding of the risk factors associated with non-compliance.

• The hospital policy and procedures should address the need for nurses to observe standard precautions on all patients, regardless of their knowledge about their infection status.

• The management of OOUTH should have a written plan of the use of PPE posted in the hospital and PPE"s should be made readily available of high quality.

• Development of specific policies on the practise of standard precautions and ensure strict implementation of these policies.

• Rewarding of the health workers who comply consistently with safety measures and penalizing those who failed to comply that is quality measure in place to monitor compliance.

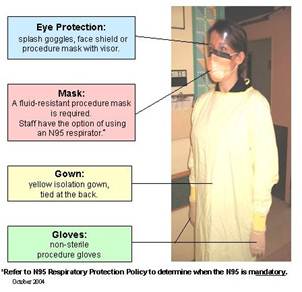

Figure 1. Researcher in a quarantine kit.

Figure 2. Component of the quarantine kit at a glance.

References

- Afolabi, G. K and Okezie G, N (2004), Edited work. Project Writing and Supervision.Gold Field Printers 18/20 Lodge Street, Oke – Ado, Ibadan. Pp 3

- Aina, J .O (2011).A handbook of research in nursing (Ed.2), Ibadan; Ibadan University Press. (pp.10-20).

- Anderson E, McGovern PM, Kochevar L, Vesley D, Gershon R. Testing the reliability and validity of a measure of safety climate. J Healthc Qual 2009 Mar ;22(2): 19-24

- Asika, M. (2004), Research Methodology. A Process Approach, Mukugamu & Brothers Enterprises, Lagos. Pp 100 – 101.

- Beekmann, S.E. & Henderson, D.K. (2005). Protection Of Health Care Workers From Blood Borne Pathogens: Current Opinion Infectious Diseases: 18(4):331-336.

- Chow, T.T., & Yang, X.Y. (2005). Ventilation Performance In The Operating Theatre Against Airborne Infection: Numerical Study On An Ultra-Clean System. Journal of Hospital Infection,59:138-147.

- Eggimann P,(2007) Prevention Of Intravascular Catheter Infection. Current Opinion In InfectiousDiseases;20(4): 360-369.

- Friedman, E.A. & Bernstein, J.D. (2003). HIV Transmission In Health Care Settings: A report on HIV transmission in Health care settings. Retrieved 12 march 2014 from; Http://S3.Amazonaws.Com/Phr.

- Garner, J. S. (1996). Guidelines For Isolation Precautions In Hospitals. The Hospital Infection ,Control Practice Advisory Committee. Infection Control Hospital Epidemiol.17: 53-80.

- Gershon, R, Vlahov, D., Felknor, S, Vesley, D, Johnson, P, Delcios, G. & Murphy, L (1995). Compliance With Universal Precautions Among Health Care Workers At Three Regional Hospitals Of Infection. American Journal Control, 23(4): 225-236.

- Gould D, Wilson-Barnett J, Ream E. Nurses' infection-control practice: hand decontamination, the use of gloves and sharp instruments. Int J Nurs Stud. 1996 Apr; 33 (2): 143-60.

- Hammond, J. S., Eckes, J. M„ Gomez, G. A., and Cunningham, D. N. (2005). HIV, Hospital: A Nursing Perspective. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University.

- Jeong, I., Cho, J. & Park, S. (2008). Compliance With Standard Precautions Among Operating Room Nurses In South Korea. American Journal of Infection Control, 36(10): 739-742.

- Joint United Nations On Hiv/Aids (Unaids) And World Health Organization (Who). (2008) Sub-Saharan Africa.Aids Epidemic Update Regional Summary. Appia, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Levin, P.F. (1994). Improving Compliance with Universal Precautions, AAOHN. 43, (7), 362-370.

- Lewis, S, Hertkemper, M. & Dickson, S (2004). Medical-Surgical Nursing: Assessment And Management of Clinical Problems. 6th Ed. St Louis: Mosby.

- Ngesa, A. (2008). The Management of Blood and Body Fluids in A Kenyan University Hospital; A Nursing Perspective. Stellenbosch; Stellenbosch University.

- Owen, C. D. & Stoessel, K. (2008). Surgical Site Infections: Epidemiology, Microbiology and Prevention. Journal of Hospital Infection, 17: 3-10p.

- Parboosing, R., Raruk, I. & Lalloo, U (2008). Hepatitis C Virus Seropositivity In A South African Cohort of Hiv Co-infected Arv Naïve Patients Is Associated with Renal Insufficiency and Increased Mortality. Journal of Medical Virology, 80(9); 1530-1536.

- Parker, L. (1999). Rituals Versus Risks In The Contemporary Operating Theatre Environment. British Journal of Theatre Nursing, 9(8):341-345.

- Reis H & Judd C (2000), Hand Book in Research Method in Social and Personality Psychology. Cambridge University Press.

- Salkin, I. F. (2004). Review of Health Impacts From Microbiological Hazards In Health- Care Wastes, Geneva; WHO.

- Tetali S, Choudhry P (2006) Occupational Exposure To Sharps And Splash: Risk Among Health Care Providers in Three Territory Care Hospitals In South India. Indian Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 2006; 10 (1) 35-40.

- Twichell, K. T. (2003). Bloodborne Pathogens. What You Need To Know. Part1. American universal precautions in a university teaching hospital. Hospital and Health Services

- Williams, C.M. & Pieterse, V. (2005).South African Theatre Sister.Basic Peri- Operative Nursing Procedures Guideline. South Africa. 4-5