What Ails Italy: The Competitive Issue of the Italian State

Arthur Guarino1, *, Domenico De Martinis2

1Department of Finance and Economics, Rutgers University, Newark, New Jersey, USA

2Relations and Communication Unit, International Relations Office, Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development (ENEA), Rome, Italy

Abstract

Italy faces a most challenging global financial and economic crisis since the end of World War II. For an economy that grew at a rapid pace between the 1950’s and the 1980’s, Italy has seen slower growth in the last twenty years. Italian policymakers are facing a series of problems that include a contracting gross domestic product (GDP), large unemployment, especially among its young people, high government deficits, large governmental borrowing along with high interest rates, and a divisive north-south economy, to name a few. Adding to these dilemmas are its recent recessionary periods, which some liken to a depression, a decrease in domestic demand, and an exodus by highly skilled younger people for better employment prospects in other countries. Italian policymakers are trying diverse solutions to these complex problems, but are worried that they may not be enough to solve its crisis.

Keywords

European Union (EU), Bank of Italy, European Monetary Union (EMU), Stability and Growth Pact, Excessive Deficit Procedure, International Monetary Fund (IMF), European Central Bank (ECB), World Bank

Received: August 11, 2016

Accepted: September 3, 2016

Published online: November 21, 2016

@ 2016 The Authors. Published by American Institute of Science. This Open Access article is under the CC BY license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

1. Introduction

Since the end of World War II, Italy’s economy has been one of significant highs and tragic lows. The Italian economy has gone from being largely agriculturally-based to an advanced industrialized nation, the third largest in Europe. Prior to World War II, Italy heavily relied on agriculture to sustain it, but after the war, Italy was transformed into a nation exporting its industrial products globally and highly regarded for its quality, design, and workmanship. While Italy’s reputation for agricultural products such as grapes, wine, olives, and olive oil are held in high esteem, the economy has diversified and its manufacturing products from the Golden Triangle of Milan-Turin-Genoa in the north, including chemicals, automobiles, ceramics, and clothing have become vital to its growing gross domestic product (GDP) since the 1950’s.

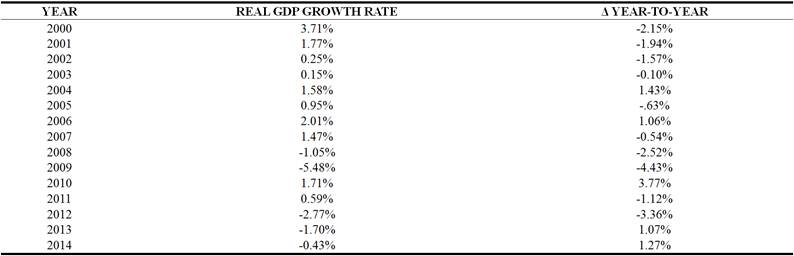

As of recently, Italy has suffered a severe contraction in its economic growth which has impacted the lives of its people and its standing in the European Union (EU) as well as globally. Italy has seen its economy stagnate, accumulate an exorbitant amount of debt, and hit with recessions in a relatively short time period. Some analysts feel that Italy is in an economic depression. The economy is in a state of uncertainty which has caused domestic spending by its people to drop precipitously, lose confidence in the central government, and in many cases, see many of its young people looking for employment opportunities elsewhere. The Italian government has tried various means to prop up Italy’s economy, from massive borrowing to austerity measures. Italy’s government has tried to privatize its many state-owned companies with the hope that, in the long run, more jobs will be created and economic prosperity will return. But it must also deal with high government deficits, lack of competitiveness within its macro-economy, a high unemployment rate, the problem of the duelling north-south economies, and the dilemma of the Euro. Italy’s policymakers are facing extremely difficult financial and economic problems. For example, according to the IMF, in terms of Real GDP growth from year to year, the situation was not good for Italy in the last decade as evidenced by the figures below:

Table 1. Real GDP growth 2000 to 2014.

Source: International Financial Statistics of the IMF and World Bank Development Indicators

The aim and purpose of this paper is to review and examine some of the key economic and financial problems Italy is facing in the last few years, and how they affect the country in the long and short term. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the employers of origin.

1.1. The Problem of Government Deficits

A key problem that Italian policymakers face deals with government deficits. Italy’s governmental budget has always been known in economic circles as one that is difficult to manage and difficult to balance. The problem of government deficits can be examined from two crucial perspectives: revenues and expenditures. For Italy, revenues are non-existent and expenditures are regarded as too high.

Tax collection in Italy is based upon labour and consumption. Italians are taxed on what they earn and many Italians complain that the tax rates are extremely high, even higher than in the United States. And due to this Italians attempt to get employment that will pay them in cash and evade income taxes. Italy also has consumption or sales taxes, on many if not all items. Many merchants, so as to obtain an advantage over others, sometimes do not collect sales taxes in order to give their customers a break. However, in recent years the Italian government, through the Guardia di Finanza, a type of government finance police, will increase the frequency of examining the receipts of exiting patrons to see whether a sales tax was charged and possibly collected in order to combat tax cheating. The Italian government is trying to change this tactic as stated by Economic and Finance Minister Vittorio Grilli in a speech in January 2013 in which he told members of the Italian Parliament that the government would be shifting its tax burden away from labour and sales taxes to taxing property as well as giving more power to local and national authorities to combat tax evasion. The Bank of Italy reported in a 2012 study that 27 percent of Italian GDP eluded taxation [1]. But this is a problem that also plagues other members of the European Union. For example, according to the consulting firm, A. T. Kearney, the share of the shadow economy in the southern European countries GDP has not changed since 2008: in Greece it is approximately 25 percent of GDP in 2013, and 20 percent in the same year in Spain and Portugal [2].

On the expenditure side, key items include public sector wages and social transfer payments such as pensions for retired workers. Italy has a national pension system, analogous to Social Security in the United States, in which each worker receives a pension for life. However, with the number of retired Italians and Europeans increasing and also living longer and the amount of working Italians decreasing, this has become a huge problem for the government [3]. Compounding this dilemma is the amount of corruption in government as well as waste, red tape, an unwieldy and unresponsive bureaucracy, and high amounts of patronage and cronyism that has increased public spending in the last decade by 50 percent without any significant public investment [4]. Italy’s governmental budget problems are serious enough that the government is forced to borrow funds at a very high interest rate, thereby increasing its national budget in order to cover interest payments to investors.

Italy’s budget deficit has been very high in recent years. This has affected Italy’s participation in the European Monetary Union (EMU) which it joined in 1998 by signing the Stability and Growth Pact. In signing this agreement and as part of its membership in the EU, Italy must adhere to the strict rule that it must keep its budget deficit below a ceiling of 3 percent of GDP. Given Italy’s tendency to high spending and the worsening economic and financial crisis globally and in Europe, matters only became worse for Italian governmental leaders [5]. In 2014 and 2015, Italy’s budget deficit was 3 percent of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product respectively. In order to rectify the situation, Italian policymakers must take drastic measures or else face financial and economic ruin. Policymakers must make short term consolidations which include drastic spending cuts to achieve long term gains, but this will not be easy. For example, the budget deficit in 2011 consisted of revenues of $1,025 billion and expenditures of $1,112 billion, or a shortfall of $87 billion [6]. Comparing this figure to Italy’s GDP, the deficit was at 3.6 percent which was an improvement to the amount for 2010 [6].

Among the measures that policymakers must attempt to implement in order to properly address the budget crisis is pension reform in which workers do not take early retirement at age 55 with full benefits. There must also be a concerted effort to combat tax evasion by workers and business owners. The government must make difficult spending cuts in the national budget as well as eradicating government inefficiencies and cutting down the nation’s bureaucracy.

Recent events in Italy have shown how difficult it will be for the government to eventually reach the 3 percent budget deficit ceiling. Prime Minister Mario Monti was ousted from government earlier in 2013 by voters who rejected his efforts to increase taxes, reduce pensions, and curb budget deficits which actually helped the Italian government avoid the precipice of insolvency and economic ruin. Italians fear austerity more so than financial ruin. Prime Minister Monti followed the EU’s preference by cutting expenses such as pensions and implemented property taxes causing a fierce uproar among the Italian populace. The uproar was so significant that one in four voting Italians rebuffed Monti’s austerity measures and at the following general elections voted the new anti-establishment Five Star Movement of the social commentator/comedian Beppe Grillo that became the third force behind the majority of the centre-left alliance and the centre-right alliance of former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi [7, 8]. In April 2013, following weeks of political deadlock, Enrico Letta, who wants to ease austerity measures and place much more of an emphasis on stimulating economic growth and creating jobs, was designated Prime Minister. "European policies are too focused on austerity, which is no longer sufficient," said Prime Minister Letta in April 2013 after being nominated by Italy’s President, Giorgio Napolitano [9]. But, Letta faced the difficult task of acquiring financial resources in order to create jobs and avoid future tax increases.

To make matters even more difficult for Letta, Italy had to adhere to strict guidelines set forth by the EU regarding budget constraints. First, the EU has a "fiscal compact" for those nations, such as Italy, that violate the deficit rules who will be punished, unless a qualified majority of other member nations allow leniency [10]. Secondly, the EU also has the "two pack" regime in which nations must submit their budget proposals to the European Commission in order to be approved or else face revisions [10]. If there is one positive note to all the problems Prime Minister Letta and Italian policymakers faced is that in May 2013 the European Commission relaxed budgetary restraints on Italy. Through this important move, the Commission released Italy from the Excessive Deficit Procedure and granted Italy a reprieve from any more budget constraints [11]. The European Commission feels that Italy has made key improvements in its budget deficit dilemma and reached the 3 percent ceiling, therefore allowing it to disregard reaching specified fiscal goals in the future. However, the relaxation of the budgetary constraints took place in 2014 and allowed Italy to have access to approximately 0 billion ($12.9 billion) in new moneys from its own treasury and EU development funds [11]. With the arrival of Renzi after a difficult negotiation to establish a consensus within the Parliament, there has been finally a switch in approaching the austerity measures [12].

1.2. Government Debt Situation

Italy’s problem with high government deficits is directly linked to its dilemma with high governmental debt. Italy must borrow on world markets in order to finance its government deficits and this runs into the trillions of Euros. Italy has a debt ratio (national debt divided by GDP) that is the second worst in the Euro zone, only behind that of Greece [13]. In 2011, Istat, Italy’s national statistical agency, reported the nation’s public debt at 120.7 percent of its annual economic output, or approximately $2.6 trillion [14]. Italy’s situation is not expected to improve anytime soon: Italy recorded a government debt to GDP of 132.70 percent of its Gross Domestic Product in 2015 [15]. However, Greece has a government debt to GDP ratio of 182 percent [14].

Italy’s borrowing situation is a severe problem, not only for Italians holding the public debt but also for investors outside of the country who hold its debt. In 2011 alone, the total amount of debt held by investors outside of Italy totalled 90 billion ($1.1 trillion) which exceeds the total amount for foreign-held bonds issued by nations such as Portugal, Greece, and Spain [16].

Italy’s high debt situation can also have long term implications for its economic growth. As stated in an occasional paper by the European Commission Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs, "high public debt could affect growth mainly via the higher ─ present and expected ─ distortionary taxation needed to service it and put it on a sustainable path. This weighs on labour and capital costs [17]." The ramifications will also be felt by the private sector due to greater risk for Italy’s macroeconomic future and higher taxes by Italy’s government in order to service its national debt. But according to Italian policymakers, borrowing is not expected to stop anytime soon. In 2013, Italy’s Economic and Finance Minister, Vittorio Grilli stated: "We will increase debt by 0 billion in 2013 and 0 billion in 2014 [18]." The hope is that by putting more money into Italy’s macro-economy this will help it recover and thereby increase long-term economic growth. The key question then becomes: Will this strategy work? This depends on a number of factors.

First, Italy must be able to maintain its relatively low level of private debt, or debt held by Italian families, and its high level of personal wealth. Italy’s private debt is below $10,000 per household, while in the United States it is $60,000 [19]. Italy has the second highest amount of private wealth in Europe of 30,200 in savings per capita which is behind France at 36,800 and ahead of Germany at 4,500 [19]. Combining Italy’s private wealth and private debt puts it miles ahead of other nations in the industrialized world regarding net savings on a per capita basis. If Italy can maintain its lead in this regard, an influx of additional capital can help its economic rebound.

Secondly, Italy must be able to use these funds to stimulate economic growth that will mean lower interest rates in the long run. Italy’s high amount of debt means high interest payments. For example, in the fourth quarter of 2012, its interest payment was 5.3 percent of GDP as opposed to 4.7 percent of GDP in 2011 [14]. Italy must also deal with the spread in interest rates versus German debt, which has become a benchmark for lending in the EU. In the last decade, the interest rate differential between Italian and German 10-year public debt increased from 35 basis points in 2007 and remained between 140 and 150 basis points in March 2009, even though the average interest cost of new debt decreased [20]. This increasing differential shows that investors are wary of Italy’s fiscal policy and the risks associated with it. In 2012, the situation did not improve as the yield between 10-year Italian government bonds and notes and their German counterparts increased to levels and rates that have never been seen since the birth of the Euro [21]. If Italy’s economy does not improve and the government is forced to increase its borrowing, the spread between Italian and German debt instruments will increase causing further investor anxieties.

Third, the influx of new funds into the Italian economy could help stave off a crisis in the nation’s banking system. Italy has been fortunate in that before and during the financial crisis of 2008-09, its banks maintained a conservative position and that the country did not have a real estate bubble as seen in the United States and Spain. But because of Italy’s debt dilemma and high government deficits, Italian banks have had a difficult time trying to access financial capital and, therefore, have had to pay higher rates despite the European Central Bank’s (ECB) decisions to reduce the main refinancing operations rates by 25 basis points in November and December of 2011 to 1 percent [22]. The situation will further worsen if the Italian government debt that Italy’s banks hold loses value if interest rates climb. To avoid this bad case scenario, the ECB would have to act quickly by purchasing more government debt on top of the $200 billion of government bonds from nations such as Greece and Spain [23].

In sum, Italy has a severe problem in dealing with its debt. Default of its bonds and notes would mean global and regional chaos and possibly cause it to have economic problems that would take years to recover. It is possible that Italy can reduce its debt load, but this means drastic measures that the Italian people may not be prepared for and policymakers will not be willing to implement.

1.3. The Competitiveness Issue

If Italy is to deal effectively with its economic and financial problems, it must improve its level of competitiveness. Italy has a number of hurdles to overcome, whether imposed by the government or its way of doing business, that must be eliminated or greatly reduced if it is to be a competitive economic and trade power and improve its financial health in order to create more jobs and increase its GDP, in the long and short term. The first of these problems with poor competitiveness is low productivity.

Italy’s productivity, which is measured in the amount of value that each worker creates over time, is quite low when compared to other EU nations such as Germany. Since the 1990’s, Italian workers have been putting in longer hours at their jobs while actually producing less [13]. Therefore, Italian workers have been making less in terms of overall production, but still seeing their wages increase over time. This has led to constant wage increases which have caused nominal unit labour costs to go up by more than 30 percent since 2000, while the increase for German workers has been less than 10 percent for the same time period [14]. This has affected Italy’s situation regarding world trade and with regards to emerging global markets [21].

Another problem regarding Italy’s lack of competitiveness is seen in the World Bank’s list of indices. The World Bank publishes a yearly index of the "Ease of Doing Business" as well as diverse rankings by an assortment of topics. For 2013, Italy was ranked 73 out of 185 economies in the category of "Ease of Doing Business" which is a slight improvement over 2012 when it was ranked at 75 [24]. However, the World Bank also rated Italy poorly in such areas as starting a business (at 84), paying taxes (at 131), enforcing contracts (at 160), and obtaining credit (at 104) [24]. If Italy is to improve its economic situation, it must make headway in how business is conducted so that it can compete with such economic powerhouses as Germany. This means making it easier for entrepreneurs to start a new business by streamlining start-up procedures, authorizations, and easing rules by reducing the nation’s regulatory bureaucracy. According to one business owner in central Italy, whose company is expanding and a success, there is a deep need for reforms: "It’s difficult for a private company like this to survive in the difficult circumstances our country throws up every day. There are too many restrictions, too many rules, they’re so complicated, so sophisticated! [25]"

Another problem Italy faces that deeply affects its competitiveness is dealing with its workforce. Italy’s labour force is divided between workers who are highly protected by permanent work contracts and those who lack protection due to temporary worker status. In this situation, permanent workers can literally have a job until they die, while temporary workers will have an employment contract for six months which is then renegotiated for the next six months. The contracts of permanent workers have little to no flexibility, while temporary workers are always on edge regarding their job stability. An example of this has recently occurred with the Whirlpool Corporation in attempting to close a manufacturing plant in Italy which would mean cutting 500 jobs by trying to convince workers to relocate to other factories or accept early retirement [26]. In the United States, this would have been done on a prompt basis, but three years later, Whirlpool has not been able to achieve all of its planned reductions in Italy [26]. To make matters worse, due to workers’ contracts that are highly rigid, being able to move workers from manufacturing refrigerators to ovens or to another plant in Italy is difficult if not impossible. While Italy’s government is attempting to rectify the situation and provide more flexibility for firms when it comes to hiring, firing, and transferring workers, there is still a great deal that must be done in order to change its labour laws thereby helping the nation become more competitive in global markets.

Finally, another hindrance to Italy’s competitiveness is that many companies are family owned and controlled. In one respect, this ensures that Italian firms will have longstanding ties to the community and its employees. However, this will also limit growth of firms since managers will be discouraged from moving up in the firm because the owner’s son or daughter will eventually run the business. Managers will hit the glass ceiling very hard and may choose to seek employment in other parts of the world in order to run firms. This is a debilitating scenario for Italy’s long term economic future since many young professionals will take their talents, experience, and intelligence to other markets and firms that will reward them handsomely. Compounding this problem is that many family-owned firms will not accept financial capital from outside shareholders but rather borrow funds from banks. Here Italian firms are limiting their growth potential by refusing to take on more risk by going with outside shareholders. This will discourage firms from growing more effectively and avoiding risks that may be necessary for the firm’s long term survival. This risk aversion may actually promote inefficiencies in Italian firms, whether manufacturing or service. In sum, Italy must become more competitive if it is to increase its GDP and survive in an increasingly global environment in which the rules of fifty years ago no longer apply to a changing international business model.

1.4. High Unemployment Rate

If there is a key problem that haunts Italian policymakers to no end it is the nation’s high unemployment rate. Compared to other members of the EU, Italy’s unemployment problem is chronic and getting worse. The chart below shows Italy’s unemployment rate compared to Germany, France and the Euro area from 2008 to 2015. Even though Italy has the EU’s third largest economy, its unemployment rate is extraordinarily high.

Figure 1. Unemployment rate for Italy, Germany, France, Euro area 2008 to 2015.

Source: OECD

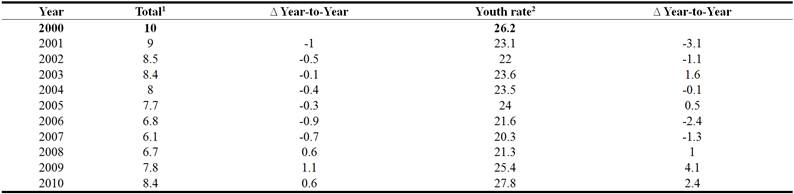

The lost decade of the 2000’s has not seen any improvement in its unemployment situation: unemployment was 8 percent in 2000 and 8.4 percent in 2010 [27]. The lost decade shows no signs of abating as Italy’s seasonally adjusted unemployment rate went to 11.7 percent in January 2013 from 11.3 percent in December 2012 which is the highest level for at least 21 years [28].

Italy’s unemployment problem is structural in nature. There are really two job markets in the country: one for older workers and one for younger workers. Senior workers are protected by governmental employment laws that are inflexible and make them almost impossible to let go. However, younger workers do not have such protection since their employment contracts are short term and they must find new jobs every six to twelve months. This makes it particularly difficult for younger workers to find and keep jobs. The numbers are astronomical:

• 44.6 percent of young women living in Southern Italy are unemployed.

• The unemployment rate for 15 to 24 year olds was 33.9 percent in early 2012 [21].

• As of January 2013, unemployment among young people reached an all-time high of 38.7 percent from a previous high of 37.1 percent [29].

A new situation that confronts Italy’s economy and its young people is the growing situation with the NEET Generation. NEET means those young people who are not in employment, education, or training. These are generally recognized as young people between the ages of 15 to 29 who lack the proper skills needed for obtaining and holding their first jobs and being able to earn a decent living. These will face long-term employment and career problems. According to the OECD more than one in four individuals age 15 to 29 years old in Italy fit into the NEET category and for a period of longer than one year in the case of one third of young people [31]. To make matters worse, in all OECD nations, low-skilled younger people have a better chance to be categorized as NEET than those who are better trained and educated. The NEET generation accounts for a higher percentage of younger people in Italy, at 10 percent, than on average in the OECD areas at under 6 percent [30].

As seen in the chart below, unemployment among young people in the lost decade has been increasing.

Table 2. Unemployment rates (%) for Italy 2000 to 2010.

1Total for nation 215-24 years old

Source: Istat, http://dati.istat.it/Index

This has caused young Italians to seek employment elsewhere in the world causing a brain drain or commonly known as la fuga di cervelli. One estimate has calculated that up to 60,000 young Italians exodus Italy yearly, and that half of Italy’s 100 leading academics and scientists are working in other countries [31]. While this is great for other nations such as the United States and Canada which could use these young, talented and highly educated minds, this will cause a severe setback for Italy in order to remain competitive in research and development and advance in science, medicine, and technology.

For 2013-2014, the unemployment rate is expected to increase due mainly to an expanding labour force. Italy’s labour force is expected to increase for two reasons. First, more people, especially women and younger individuals, will be joining the workforce as disposable income for households falls [32]. Secondly, the Italian government adopted pension reforms which have incentivized older workers to stay in the country’s workforce longer than anticipated [32]. To make matters worse, Italian manufacturers have been reducing the number of workers by cutting staffing at a rather solid and accelerated rate, as of January 2013, to 47.8 million workers [33]. This has extended the continuing number of job reduction in Italian manufacturing for the past year-and-a-half [33].

Italy’s political leaders are trying to take drastic measures in order to deal with its unemployment problems. In June 2013, Prime Minister Enrico Letta introduced a package of measures designed to reduce youth unemployment. Letta’s plan introduced a .5 billion program that included job training, and incentives to cut payroll taxes for firms hiring individuals ages 18 to 29 under permanent, full-time contracts for those not in school [34]. While this plan helps 200,000 young people find work, this is only a small amount of the unemployed, which as of June 2013 stood at approximately 40.5 percent [34].

In 2014, Prime Minister Matteo Renzi was able to have the Jobs Act passed by the Italian Parliament in order to help reform the nation’s labour market. The Jobs Act has put in place rules and regulations that are considered reformist by Italy’s standards. These reforms include modification of all labour contracts, revision of the rules accessing social security, and the reformation of policies in order to help those unemployed find new job opportunities. The Jobs Act could be regarded as radical by Italian standards since it also provides simplification to the nation’s labour code so that it is now easier for firms having over 15 employees to terminate their employment, while also linking workers’ protection to their length of employment [35]. This legislation now gives employers more flexibility in hiring and firing workers and expanding and contracting the workforce when needed. However, the bottom line is that Italy still has a long road to travel in order to deal with its unemployment problem and this may take years to solve.

2. Lack of Innovation

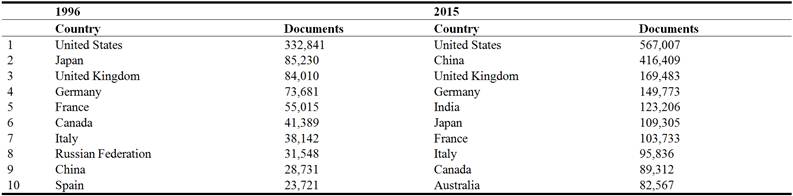

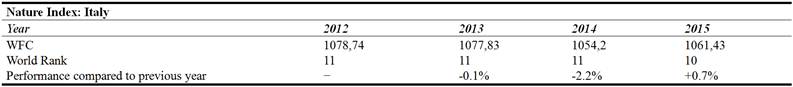

Poor competitiveness and high unemployment previously discussed may be linked to lack of innovation rate of the Italian productive system in the last few decades. Italy developed quickly between the end of the Second World War and the late 1960s, in years of reconstruction that resulted in a general post-war reconstruction trend that characterized most of the European states [36]. This period, called "the Italian economic miracle", corresponded to a flourishing economy and a demographic boom, low labour costs and a need for modernization, especially in terms of energy demand and infrastructures that were made. Since the early 1970s the Italian economy has been moving towards a financial crisis. A reason for this is identified with a lack of investment in education, research and technological innovation. The Italian scientific community strongly complains about a chronic lack of public funding dedicated to education and research that would be the core strength of an industrialized and technologically evolved country. The discussion about the lack of research funds continues for years in major Italian newspapers as well as international scientific journals [37]. Nevertheless, main statistics keep mentioning Italy as a top research country worldwide [38] (Table 3) with fairly good public universities [39]. Nature Index [40] placed Italy 10th in the world ranking of scientific excellence indicating an increasing trend since 2012 (Table 4).

The quality of the overall knowledge produced by Italy is even more stunning if we consider the low number of researchers [41], the low number of researcher per inhabitant if compared to other EU member states, and if compared to investment/PIL and investment in education so far. Statistics therefore depict a country that in the last decades, generated excellent individualities that produced high level research although the government policies, as implemented so far, did not provide a strong support over the years. So is Italian education, science and technology issue, really an issue? And where is the problem? We recently suggested that the scepticism about the Italian scientific system cannot be associated neither to the lack of quantity nor quality, but in the relation of Italian science with industry [42]. This is a crucial aspect as to enable private funding of public research would lower investment risks for innovation of industry and provide direct returns to the scientific community, with a targeted feed to research. That would also somehow give a pace and direction to research planning.

Yet just adding more technological transfer to the recipe may not be sufficient if the industrial system is not ready to absorb the technological offer. The absorption capacity of a national industrial system is essential to assimilate a novel technology and derive the benefit from a novel technology. The flow of innovation is vital to Italy’s economic and financial long-term future.

Connecting knowledge, practice, and policy, as suggested is not utopia and is well defined and occurring traditionally in the United States, but also in EU member states [43]. The conundrum then, should be in the idea that betting, investing, solely on academic rather than creating the conditions for industrial renovation would create a long queue of competent and valuable scientists with little professional perspectives, one that would result in broad non-selective hiring processes in the public administration and a brain drain [44] for those that are excluded. Investing in technological transfer would instead on one side create alternative job opportunities (related to application of technologies and non-academic studies in general) and produce on the other side also an economical feedback on education and academics granted by industry.

Table 3. Top ten world countries in terms of scientific production in 1996 and 2015 (from SJR — SCImago Journal & Country Rank, last retrieved 03/08/2016). Over the decades Italy’s rank moved down from 7th to 8th, while the entry of India in the top ten and the rise of China is significant.

Table 4. Italy’s performance in terms of Weighted Fractional Count (WFC) of scientific production from 2012 to 2015 according to Nature Index.

3. Conclusion: Changes Are Needed

Italy’s economic situation and the relative policy choices must be framed in the European Union’s situation, including the most extreme cases of Greece [45], Spain and Portugal [46], and more recently, the so-called Brexit [47]. The Union and the Eurozone in particular, affect the actions to be taken by member states, but in dire straits some states like Germany [48] are paving the way for a recovery despite all odds.

Italy suffers from political instability, economic stagnation, and lack of structural reforms that date earlier than the financial crisis although they have been exacerbated by it. In 2009, the economy suffered a hefty 5.5 percent contraction—the strongest GDP drop in decades. Since then, Italy has shown no clear trend of recovery. Thus, Italy faces a number of important challenges, among which are unemployment, the weaknesses of the Italian labour market, growing global competition, and the country’s public finances. In 2013, Italy was the second biggest debtor in the Eurozone and the fifth largest worldwide [49].

Italy also must deal with an economy that needs to diversify into areas such as high technology, more investment in research and development, simplification of its tax system, improve its educational system, enhance labour market participation, encourage more foreign direct investment, and solve the North-South problem. Italian policymakers must find ways to structure a national budget that will encourage economic growth, but also minimize or possibly eliminate a wasteful and inflexible governmental bureaucracy that many business owners must deal with daily. Italy, while noted for its wine, food, fashions, and many manufactured products, must do more to encourage the service sector in order to make the nation more competitive in the EU and globally.

Changes are needed in terms of infrastructure and governance in order for Italy to be a competitive and reliable fellow member of the EU, with other governmental entities, world financial markets, and investors.

Economics does not exist in a vacuum. Economic crisis and lack of competitiveness have generated in the Italians a level of anxiety and frustration that have resulted in massive vote protests and Italy’s policy makers must take action for new and revolutionary measures while also explaining to the public that economic changes can occur for the sake of the country and for the creation of new job and investment attractiveness for the future. If these changes are not decided upon and implemented by the nation’s policymakers nor are they accepted by the Italian people, then Italy’s economic standing will continue to stagnate in the wake of the global economy without having the capacity to decide within the European Union [50] or not even decide its own course.

References

- Benjamin Fox, "Italy to Run Balanced Budget, Minister says," EUoberver.com/Economic Affairs, 21 January 2013: http://www.EUobserver.com

- Giovanni Legorano, "Europe’s South Tackles Tax Evasion – Again", The Wall Street Journal, 22 January 2015: http://www.wsj.com/articles/Italy-and-neighbors-struggle-to-tackle-tax-cheats-1421969741

- OECD Data Elderly Population, https://data.oecd.org/pop/elderly-population.htm

- Mauro Gilli, "Italy: A Tale of Self-Destruction," Fair Observer, 23 August 2011: http://www.fairobserver.com

- Italy Government Budget, http://www.tradingeconomics.com/Italy/Government-Budget

- Alina-Petronela Haller, "Italian Economic System in Conditions of Crisis," Economy Transdisciplinarity Cognition, Volume 15, February 2012, p. 28: http://www.ugb.ro/etc

- Italian General Election, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Italian_general_election,_2013

- "What Berlusconi’s Return Means for Europe," Bloomberg Businessweek, 4 – 10 March 2013: 12.

- Giada Zampano, "Italian Centrist Picked for Prime Minister," The Wall Street Journal, 25 April 2013: A8.

- Buttonwood, "Caveat voter," The Economist, 18 May 2013: 79.

- Christopher Emsden, "Europe Loosens Reins on National Budgets," The Wall Street Journal, 30 May 2013: A12.

- James Polti, "Eurozone austerity fanning populist flames, says Renzi", Financial Times, 21 December 2015: http://on.ft.com/1NHIOWi

- Jordan Weissmann, "4 Reasons Why Italy’s Economy is such a Disaster," The Atlantic, November 2011: http://www.theatlantic.com/business

- Stefan Scheurer, "Structural and Fiscal Measures in Italy," Allianz Global Investors, February 2013: 2.

- Italy Government Debt to GDP, http://www.tradingeconomics.com/Italy/government-debt-to-gdp

- J. H., "Italy’s economy: Even Italy’s Politicians as Scared," Newsbook, 15 July 2011: http://www.theeconomist.com

- "European Economy", Occasional Papers 107, July 2012, Macroeconomic imbalances – Italy, European Commission Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs: 12.

- "Italy tries for stimulus, at a cost," Euronews: http://www.euronews.com

- Roland Benedikter, "The European Debt Crisis 2011-12: The Case of Italy," The European Financial Review, 17 April 2012: http://www.EuropeanFinancialReview.mht

- "Economic Survey of Italy, 2009," Policy Brief, June 2009, OECD: 4.

- Elisa Cencig, "Italy’s economy in the euro zone and Monti’s reform agenda," Working Paper FG 1, 2012/05, September 2012, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP) German Institute for International and Security Affairs: 16.

- "European Economy", Occasional Papers 107: 12.

- John H. Makin, "How Did Europe’s Debt Crisis Get So Bad?", American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, December 2011: 4.

- Ease of Doing Business, World Bank, 2013: http://www.WorldBankGroup.mht

- Dominic Laurie, "Italian Politics Hold Back Economy," BBC News, 7 April 2008: http://www.BBCNews.mht

- James R. Hagerty and Deborah Hall, "How to Cut a Job in Italy? Wait, and Wait Some More," The Wall Street Journal, 21 May 2013: B1.

- Italy UN data, United Nations Statistics Division 2013: http: www.//UNdatacountryprofileItaly.mht

- "Italy Jobless Rate Jumps to Record High of 11.7 Percent in January," Europe: Economy, 1 March 2013: http://www.Reuters.com

- "Italy Jobless Rate Jumps to Record High of 11.7 Percent in January," Europe: Economy.

- "Employment Outlook 2016," OECD Employment Outlook 2016, June 2016: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9572784d-en

- Fiona Ehlers, "Italy’s Lost Generation: Crisis Forces Young Italians to Move Abroad," Spiegel Online International, 6 August 2012: http://www.SpiegelOnline.com

- "Italy: Uncertainty and tight financing conditions delay recovery," European Economic Forecast, Autumn 2012: 73.

- Shaun Richards, "With employment falling so fast how can Italy’s economy recover?" Mindful Money, 5 February 2013: http://www.MindfulMoney.com

- Giada Zampano, "Italy Advances Plan to Ease High Youth Unemployment," The Wall Street Journal, 27 June 2013: A14.

- Roger Cohen, "Trying to Reinvent Italy", The New York Times, 13 December 2014: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/14/opinion/sunday/roger-cohen.html

- Excluding in this case the European countries belonging to the former USSR, that had a different development profile.

- E. Cartlidge. "Italian scientists protest ‘serious neglect’ of research", Science DOI, 2016: 10.1126/science.aaf4123

- SCImago Journal & Country Rank, http://www.scimagojr.com/

- Center for World University Rankings (CWUR) http://cwur.org/2016.php

- Nature Index, http://www.natureindex.com/annual-tables/2016/country/all

- Elsevier’s International Comparative Performance of the UK Research Base, p. 82, Research Productivity.

- Domenico De Martinis, "Re: The Italian Paradox in research continues (but, does it really exist?)" SCIENCE, 2016 eLetters http://science.sciencemag.org/content/351/6278/1127.e-letters

- OECD Food and Agricultural Reviews, "Innovation, Agricultural Productivity and Sustainability in the Netherlands", p. 136, ISBN: 9789264238459.

- "No Italian jobs - Why Italian graduates cannot wait to emigrate", The Economist, January 6, 2011:http://www.economist.com/node/17862256

- "Greece bailout: Eurozone deal unlocks 0.3bn", BBC News, 25 May 2016: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-36375973

- European Commission - Press release, "Stability and Growth Pact: fiscal proposals for Spain and Portugal", Brussels, 27 July 2016: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-16-2625_en.htm

- http://www.economist.com/Brexit

- OECD Economic Survey of Germany 2016: http://www.oecd.org/germany/economic-survey-germany.htm

- Italy Economic Outlook Focus Economics: http://www.focus-economics.com/countries/italy

- "Could Italy be the unlikely saviour of Project Europe?", The Guardian, 29 April 2016.