Health System Financing in Bangladesh: A Situation Analysis

Anwar Islam1, *, G. U. Ahsan2, Tuhin Biswas3

1School of Health Policy and Management, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

2School of Life Sciences, North South University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

3Department of Public Health, North South University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Abstract

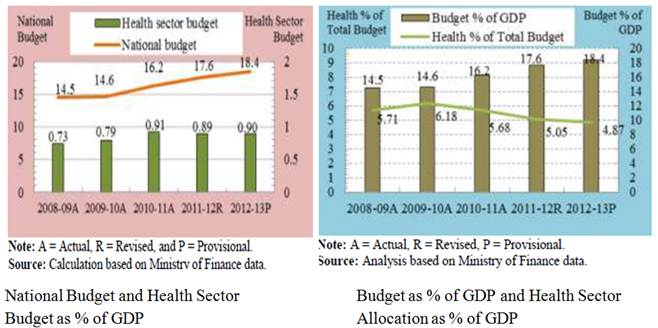

The financing of health care in Bangladesh primarily comes from three sources - the public exchequer, out-of-pocket payments by the users, and foreign aid from the development partners. Social and private insurance and official user fees comprise a very small proportion of the total funding. Using available secondary data, the paper is aimed at providing a comprehensive analysis of the dynamics of health care financing in Bangladesh. Bangladesh spends only about 3.5% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) on health. The per capita per annum health expenditure is about USD 27. It is important to note that about 63% of the total health expenditure is out-of-pocket expenses. Over the years the government’s share in the total health expenditure has declined considerably and it currently stands at around 35% of the total. Budget analysis shows that the national budget as a per cent of GDP has increased from 14.5 per cent in FY 2008-09 to 18.4 per cent in FY 2012-13. However, the health sector budget as a per cent of the national budget has declined from 5.71 per cent in FY 2008-09 to 4.87 per cent in FY 2012-13. On the other hand, financial allocation for the health sector remained stagnant at 0.9 per cent of the GDP over the last three fiscal years (2010-11 to 2012-13). Evidence suggests that district and sub-district level allocations for health under the revenue budget are determined by norms that relate to the number of beds (for food and drugs) and staff in facilities (for salaries) rather than the population size and other demographic and epidemiological measures reflecting health needs giving rise to serious inequity in resource distribution. It is apparent that Bangladesh needs to spend more on health care and at the same time make every effort to use its existing health care resources more effectively and efficiently. Exploring alternative sources of funding for the health system including social and other forms of insurance should be a priority for Bangladesh. Moreover, exploring alternative sources of funding must go hand in hand with increasing the overall health budget. In order to achieve and sustain Universal Health Care (UHC), Bangladesh has no alternative but to significantly increase public funding for the health system and at the same time promote and protect equity.

Keywords

Healthcare Financing, Gross Domestic Product, Equity, Pressure Groups

Received: May 8, 2015

Accepted: July 15, 2015

Published online: July 29, 2015

@ 2015 The Authors. Published by American Institute of Science. This Open Access article is under the CC BY-NC license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

1. Introduction

The Government of Bangladesh is constitutionally committed to ensuring the provision of basic medical requirements to all segments of the population in the country [1]. Within the broader context of the Bangladesh National Strategy for Economic Growth, Poverty Reduction and Social Development (Bangladesh I-PRSP, March 2003), the Government’s vision for the health, nutrition and population sector is to create conditions whereby the people of Bangladesh have the opportunity to reach and maintain the highest attainable level of health [2]. It is a vision that recognizes health as a fundamental human right and, therefore, stresses the need to promote health and to alleviate ill health and suffering in the spirit of social justice [3].

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW) of Bangladesh acts as the steward of the health sector providing overall leadership in policy and program development as well as monitoring and evaluation. However, the responsibility for the provision of health services is divided into two directorates - the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS) for health services, and the Directorate General of Family Planning (DGFP) for family planning services [4, 5]. Each of these directorates is headed by a Director General reporting directly to the Secretary of Health, the highest ranking bureaucrat in the MOHFW. The MOHFW provides health care and family planning services through a number of organizations, such as medical college hospitals, specialized hospitals, district hospitals, Upazila Health Complexes (UHC), Union Health and Family Welfare Centers (UHFWC), rural dispensaries and community clinics (CCs). The UHCs, UHFWCs, rural dispensaries and CCs form the Primary Health Care sub-system of the health system [6, 7].

Health financing in Bangladesh is dominated by the private out-of-pocket expenditure [8, 9]. This is by far the largest source of health financing. All public resources only make up ¼ of the total health expenditure (THE). Social and private insurance and official user fees in public facilities comprise a very small proportion of the total health expenditure [10, 11]. Government health expenditures are principally undertaken by the central government, funded mainly through general revenue and support from international development partners [12, 13]. Government’s revenues are mobilized through tax and non-tax revenues [14]. Most of the taxes are collected from indirect taxes on goods and services, while the non-tax revenue includes borrowing from the domestic market and self-financing by government-owned autonomous corporations [15]. Public sector health expenditure consists of expenditures by the MOHFW, other Ministries, Local Governments, GOB owned corporations and autonomous or semi-autonomous bodies [16]. The MOHFW is one of the largest ministries in terms of budgetary allocation [17, 18]. It works as a financial intermediary of the GOB; it receives funds from the Ministry of Finance (MOF) and the development partners, and allocates funds to health facilities and centers at different levels. More than 90% of all public funds for the health system flows through the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.

2. Findings

Total health expenditure (THE) in Bangladesh is estimated at Taka 325.1 billion ($4.1 billion) in 2012 [19]. The average annual growth rate in THE between 1998 and 2007 in nominal terms was 12.7%, increasing from 11.2% during 1998–2002 to 14.2% during 2003–2007. In 2012 the total health expenditure grew at an average of around 14 % in nominal terms. In real terms, overall total health expenditure more than doubled between 2007 and 2012, from Taka 160.9 billion in 2007 to Taka 325.1 billion in 2012 (constant 2012 prices). The total health expenditure has increased further in recent years. Unfortunately no official information is yet available in this regard.

It is clear that Bangladesh spends too little resources (as a percentage of its GDP) on health care. It is important to note that the THE as a percentage of the GDP increased only marginally between 2007and 2012 – from 3.3% to 3.5% of the GDP, an increase of less than 1% in a decade. It should be noted that during this decade (2007-2012) the overall economy of Bangladesh grew by an average of about 8% annually [19]. Table-1 presents the GDP growth of Bangladesh since 2005.

Table 1. Bangladesh GDP in PPP Terms, 2005-2014(in Billions of US$).

| Year | GDP |

| 2005 | 246.47 |

| 2006 | 270.99 |

| 2007 | 297.84 |

| 2008 | 321.95 |

| 2009 | 340.76 |

| 2010 | 364.14 |

| 2011 | 395.68 |

| 2012 | 429.05 |

| 2013 | 461.63 |

| 2014 | 497.02 |

Source: Ministry of Finance; Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, 2015

In short, the GDP grew from USD 246.47 Billion in 2005 to USD 364.14 Billion in 2010 and to USD 497.02 Billion in 2014 – growth of more than 102% between 2005 and 2014. During the same period, the total health expenditure, on the other hand, increased by about 13%. If only the public funding for health care in considered, the situation is far worse.

Households, paying fees at the point of service constitute the main source of financing for healthcare in Bangladesh, comprising 63% of the THE in 2012. In 1997, households accounted for 57%, of the THE and this ratio has increased over time [20]. For example, household expenditures on health has increased steadily as a share of GDP from 1.5% in the late 1990s to slightly over 2% in recent years [21]. Figure-1 presents sources of financing in the Total Health Expenditure.

Over the years the overall government financing in of the health sector (primarily channeled through the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare) has increased significantly. For example, it increased from 17,064 Million Taka in 1997 to 75,071 Million Taka in 2012. However, the government’s share in the THE registered a substantial decline over the same period - from 37% in 1997 to 23% in 2012. As a financing source, Voluntary Health Insurance Payment (NIPSH, Employers and Others) accounted for only 5.25% of the Total Health Expenditure [22]. According to BNHA estimates in 2012 the Non-government Organizations providing services to individuals and households contributed Taka 6 billion to the THE (approximately 2% of the total). On the other hand, various development partners contributed an additional Taka 27 billion to the health sector (about 8.4% of the THE). Some of these funds also flowed through the NGOs [23].

Figure 1. Total Health Expenditure by Source of Financing.

Source: Bangladesh National Health Accounts, 2012.

Figure 2. Regional distribution of THE.

Source: Bangladesh National Health Accounts, 2012.

Expenditure on health varied greatly across different administrative divisions within Bangladesh. According to 2012 Bangladesh National Health Accounts, the per capita health expenditure was highest in Dhaka Division that includes the capital city of Dhaka (Taka 2,722). On the other hand, it was lowest in Sylhet Division (Taka 1,379 per capita). Regional disparities are also evident when their share in the THE is considered. While Dhaka consumed more than 41% of the THE, the share of Barisal and Sylhet districts in the Total Health Expenditure were only 4.9% and 4.35% respectively. It is clear that there is significant regional disparity in health expenditure in Bangladesh. Figure-2 presents the regional distribution of THE as well as the per capita health expenditure by different regions.

3. Out-of-Pocket Health Expenditure

Out-of-pocket payments are, by their very nature, inequitable and inefficient [24]. OOP punishes the poor and discourages them from using health care services. It is alarming that in many developing countries, including Bangladesh, OOP is on the rise as a percentage of the THE [25]. Unless this trend is decisively reversed, it would be extremely difficult if not impossible for Bangladesh to achieve Universal Health Care. OOP share in the THE has increased from 55.9% in 1997 to 59.9% in 2005 to 63.3% in 2012. For households drug costs constitute the overwhelming share of their out-of-pocket expenditure on health. Expenditure on drugs as a percentage of OOP, however, has declined over time. In 1997, drug outlay was 75.3% of the total OOP, 70.5% of the total in 2001 and 65% in 2012. In 2012, households spent Taka 134 million on pharmaceutical drugs, Taka 44.8 million on curative care, and Taka 17.8 million on ancillary services. Ancillary services include various diagnostic services such as laboratory tests, imaging, etc. Figure-3 presents the share of different typed of services in the OOP.

Figure 3. Distribution of OOP by Types of Services, 2012.

Source: Bangladesh National Health Accounts, 2012.

4. Health Budget

The MOHFW is one of the largest ministries in terms of budgetary allocation to health care (MOHFW, 2003) [18]. It works as a financial intermediary of the Government of Bangladesh; it receives funds from the Ministry of Finance (MOF) and the development partners, and allocates funds to health facilities at different levels. More than 95% of all public funds for health flow through the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.

However, allocations for health remain relatively small in the budget. Since 2007/08 funding for health hovered around only 6% of the overall budget. In the revenue or non-development budget (representing three-fourths of the total budget), the share of health ranged from 5% in 2007/08 to 4.8% in 2010/11. In the development budget, it ranged from 9.7% in 2007/08 to 8.7% in 2010/11 (Table 1).

An explanatory note on the "revenue" and "development" budget is warranted. In Bangladesh, the government prepares two types of budget: a revenue budget (non-development budget) and development budget [26]. The revenue budget is meant to meet the regular expenditures while the development budget includes project related allocations for development spending. The MOHFW, as with all other government ministries in Bangladesh, is also funded through the development budget in the form of the Annual Development Program (ADP) and the non-development or revenue budget. Both the development partners and the GOB finance the development budget, while the revenue budget is solely funded by the GOB. The revenue or non-development budget is larger comprising almost three-fourth of the total budget.

The two budgets of MOHFW are prepared separately by different units and staff, and at different times of the year. The MOHFW, development partners and a separate Planning Commission under the Ministry of Planning are involved in preparing the development budget. The offices of the Director General of Health Services and the Director General of Family Planning Services within the MOHFW prepare the revenue budget. It is interesting to note that the two budgets follow different approaches of budgeting. The development of the annual development budget follows a program budgeting approach; while the revenue budget follows a line item based incremental approach of budgeting [27].

Both budgets contain capital and recurrent spending. In 1999/2000, at the very early stage of implementing the HPSP, 15.8% of the total development budget was spent for capital items, much of which was used for constructing community clinics. The rest of the development budget (84.2%) was spent on recurrent items (55% for non-salary items and 29.2% for salary and allowances). In 1999/2000 capital spending under the revenue budget was 1.3% of the total, and the rest (98.7%) was on recurrent expenditure (66% to salary and 32.7% to non-salary items). The proportion of capital spending in the revenue budget rose to 3% in 2003/04. During the five years of HPSP, the proportion of the development partners’ contribution to HPSP stood at around 66%, which fell to 54% during the first three years of HNPSP.

A number of serious obstacles within the health system including widespread corruption, reduced foreign aid flow, drainage on public funds by inefficient public facilities, lack of fiscal accountability, weak overall development planning and poor absorptive capacity are hindering the resource allocation and budgeting process of the sector [28, 29]. Moreover, the inefficiency of the system of allocating health care resources from national to local level is perhaps one of the major obstacles to universal access to quality care leading to significant inequity in health status among different socio-economic groups [30]. The Bangladesh public health expenditure pattern appears to be regressive allocating more resources to richer districts than to the poorer ones [31, 32]. Influential socio-political and economic elites are mostly concentrated in richer districts [33]. They usually weigh more heavily in the political process of resource allocation. Nevertheless, this has attracted the attention of policy makers in recent years primarily due to the continued advocacy from NGOs and civil society groups. Table-2 presents the allocation of financial resources to health in 2007/08 to 2010/11.

Table 2. Bangladesh budget: investment in health.

| Total Health Expenditure in the Budget | 2007/08 | 2008/09 | 2009/10 | 2010/11 |

| (BDT Billions) | 796.14 | 999.62 | 1,138.19 | 1,321.70 |

| Health as a % of the Total Budget | 6.60 | 5.90 | 5.90 | 6.20 |

| Health Allocations in Non-Dev Budget (BDT Billion) | 526.50 | 725.85 | 821.80 | 924.76 |

| Health as a (%)of the Non-Dev Budget | 5.00 | 4.30 | 4.40 | 4.80 |

| Health Allocation in Dev Budget (BDT Billions) | 269.64 | 273.79 | 316.39 | 396.94 |

| Health as a (%) of the Dev Budget | 9.70 | 8.90 | 9.70 | 8.70 |

Source: Ministry of Finance (GOB). Budget in Brief (various years)

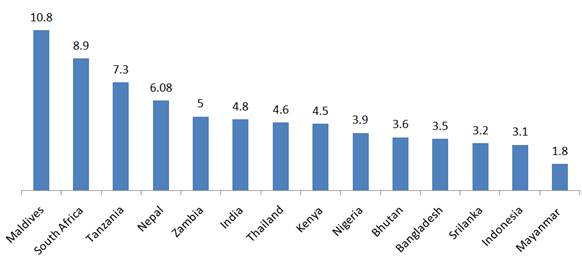

Although allocation for health increased substantially since 2007/08, it remained stagnant as a percent of the total budget (Figure 4). At the same, as noted earlier, Bangladesh spends a much lower percentage of its GDP on health (Figure-5). For example, while Maldives spends 10.8% of its GDP on health, the figure for Bangladesh is only 3.5%. Similarly, South Africa and Tanzania spends 8.9% and 7.3% of their GDP on health respectively. Even Nepal spends more than 6% of its GDP on health. Clearly Bangladesh can and should allocate significantly more of its GDP to health. It should be noted that if OOP contributions are excluded, Bangladesh spends barely 1.5% of its GDP on health.

5. Discussion

In the last three decades Bangladesh has achieved commendable progress in health and socio-economic development. The remarkable achievements of the health sector are in unison with the overall development process. Bangladesh has made significant progress in basic health indicators in recent years - infant and maternal mortality rates have declined, immunization coverage has increased, a number of epidemic diseases have been eradicated, and overall morbidity has declined [33, 34]. Life expectancy at birth for both males and females has gone up since the 1980s [35]. Most importantly, the gender gap in life expectancy at birth – so prevalent since the independence of the country in 1971 has completely disappeared in recent years. Infant/child mortality and fertility rates have also declined significantly [34].

Figure 4. National Budget and Health Sector Budget: 2008/09 – 2012/13.

Figure 5. Total Health Expenditure as a % of GDP in Selected Countries, 2013.

Source: World Bank 2013.

Despite these achievements, the health sector faces multifarious challenges in ensuring universal access to basic healthcare and providing services of acceptable quality; improvement in nutritional status, particularly of mothers and children; prevention and control of major communicable and non-communicable diseases; supply and distribution of essential drugs and vaccines; survival and healthy development of children; the health and well-being of women; reducing financial burden on households due to increasing health care costs and the adoption and maintenance of healthy lifestyles. Resource constraint poses a serious problem to meet these challenges. Bangladesh currently allocates inadequate fiscal resources for health because of relatively small tax base and the resultant scarcity of resources. Thus, there is a need to expand the tax base to generate more revenues and at the same time explore avenues for generating additional resources for health. In this respect, it is high time to explore and introduce various types of health insurance programs including community health insurance schemes with a view to generate additional resources for health.

First and foremost, Bangladesh must give priority to health and allocate a much greater proportion of its budget for health care. This would also require systematically expanding the tax base in order to generate more public resources for health. Given the robust GDP growth (averaging almost 6% during the last decade and expected to continue), it should not be difficult for Bangladesh to significantly increase its allocation for health. The government and the polity at large must recognize health as a fundamental human capability essential to enjoy life as well to be productive members of the society. In other words, the intrinsic as well as the instrumental value of health must be equally recognized.

Second, Bangladesh needs to invest in improving the infrastructural facilities of the health system. This initial investment is required to improve the quality of health care services available at public health facilities. As noted in the previous section, without such initial investment and substantial improvement in the quality of services, the public health system would fail to attract the well-to-do classes to its facilities. These are the people who could "pay" for their health care services and subsidize the poor. The development partners can play an important role in contributing to this initial investment for strengthening and enhancing the health system.

Compulsory social health insurance has its benefits. International literature suggests that, there are three main benefits of insurance (Abel-Smith, 1992; Normand, 1999). First, it has the potential to expand the revenue base for improving quality of existing services as well as to extend coverage to a greater proportion of the population. Second, it can provide protection against high and often catastrophic out-of-pocket expenditures incurred for health care. Finally, it could help develop the system’s capability to obtain (purchase) services in a more cost-effective manner. Countries that introduced health insurance realized some of these benefits. In China and India heavily subsidized health insurance plays an important role in mitigating the societal burden of financial catastrophe that many face in obtaining health care in Bangladesh as well as in many other developing countries.

However, in the context of Bangladesh greater caution must be used before introducing any community-based health insurance. While social insurance may generate additional funds from the well-to-do classes (only if the quality of services can be improved through initial investment to lure these classes of people to the public health system), the poor must be covered through public funding. That would require massive infusion of public funding for the health system. A combination of these strategies – initial investment to improve quality of services, full public funding for the poor, and infusion of significant additional public resources – could pave the way for introducing community-based social health insurance. For universal health coverage, policy makers need to carefully project the minimum amount of resources the GOB needs to spend, and the possible ways to generate the required amount of money (income tax, other taxes, donor contribution). Social health insurance can be initiated as a financing mechanism with the aim to strengthen the financial risk protection, and extend health services and population coverage, with the ultimate aim to achieve universal coverage.

However, introduction of community-based social insurance system will require a fundamentally different skills-set for those in charge of the health system at the local level. It would require creation of a separate organizational entity to manage the SHI separating the payer and the provider of health services. Strengthening the monitoring mechanism along with a strong health information system would be essential for this purpose. Establishment of a devolved health system ensuring a greater decision-space to the local level is also an important pre-requisite for enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of the system. Increased work load due to increased number of clients may influence the human resource management issues within facilities. This may also require a strong referral linkage among different levels of public health facilities, or even referring patients to private/NGO facilities, if requires. Implementing explicit insurance schemes will require skills in finance, accounts and management. To make decisions about whether or not to scale up insurance schemes, stakeholders need to be fully informed about how organizations respond to the adjustments required for financing and delivering the benefit package through an insurance scheme. It is, therefore, crucial to have detailed cost information on availability of human resources, their competencies, availability of physical infrastructure, medicines and logistics and the existing referral system of health facilities at different levels to meet the needs of the benefit package offered by the insurance scheme.

A benefit package needs to be identified for the insurance, which should include services that have important externalities. In the case where there is no externality from non-treatment as in the case of maternal health or chronic non-communicable diseases, they might be initially targeted at low income groups. A referral linkage must be designed and implemented for the services not covered by the benefit package. Non-governmental organizations (NGO) may be entrusted with the provision of improved service package to the target groups. However, as noted earlier, adequate public funding must be there to ensure universal accessibility to the essential package for the poor.

For designing and implementing the health insurance and providing a benefit package, the government must have coherent organizational structures, technically competent staff, and an effective intergovernmental structure which allows efficient resource generation, information flow and efficient and effective implementation at national, regional, and local levels. Government can introduce the scheme in phases. At first, government can conduct pilot projects in selected areas, and can then scale up based on lessons learnt from the pilot projects. Along with the public sector, NGOs can also be encouraged to provide social health insurance. For example, NGOs involved in providing micro credit can start providing health insurance to their clients.

6. Conclusion

In closing, Bangladesh needs a three-pronged approach to introduce and sustain universal health coverage for all based on a prudently fashioned essential package of services. First, the country must significantly increase its public funding for health care so that the poor are never deprived of essential health care services. Second, Bangladesh needs to invest "heavily" in improving the infrastructure of health facilities so as to enhance the quality of services offered. Such initial investment (donors can play a critical role in this) is essential to improve quality of services and thereby attracting the well-to-d- classes to publicly funded health system. Third, on a pilot basis Bangladesh should experiment with various kinds of health insurance schemes including community-based social health insurance to generate much needed additional resources from the well-to-do classes. Lessons learned from such pilot projects could be replicated widely. Such a three-pronged approach could be pivotal in designing, implementing and sustaining universal health coverage in Bangladesh on the basis of an essential package of services. Clearly significant scaling of public funding for health care is the fundamental building block of such a three-pronged approach for ushering in universal health care in Bangladesh. At the same time, the country must work diligently in reducing the out-of-pocket expenses on health care so that the fundamental principle of equity can be maintained and further strengthened.

References

- Islam, M.S. and M.W. Ullah, People's participation in health services: A study of Bangladesh's rural health Complex. 2009: Bangladesh development research center (BDRC).

- Gwatkin, D.R., A. Bhuiya, and C.G. Victora, Making health systems more equitable. The Lancet, 2004. 364(9441): p. 1273-1280.

- Health, W.C.o.S.D.o. and W.H. Organization, Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health: Commission on Social Determinants of Health Final Report. 2008: World Health Organization.

- Vaughan, J.P., E. Karim, and K. Buse, Health care systems in transition III. Bangladesh, Part I. An overview of the health care system in Bangladesh. Journal of Public Health Medicine, 2000. 22(1): p. 5-9.

- Bhatia, S., et al., The Matlab family planning-health services project. Studies in family planning, 1980: p. 202-212.

- Uddin, J., S. Momtaz, and M.S. Islam, State Obligation towards the Fulfillment of the Right to Health: A Study in Bangladesh Perspective. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 2013. 4(13): p. 73.

- El Arifeen, S., et al., Community-based approaches and partnerships: innovations in health-service delivery in Bangladesh. The Lancet, 2013. 382(9909): p. 2012-2026.

- Xu, K., et al., Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. The lancet, 2003. 362(9378): p. 111-117.

- Saksena, P., et al., Health services utilization and out-of-pocket expenditure in public and private facilities in lowincome countries. World health report, 2010.

- Green, A., The role of non‐governmental organizations and the private sector in the provision of health care in developing countries. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 1987. 2(1): p. 37-58.

- Carrin, G., M.P. Waelkens, and B. Criel, Community‐based health insurance in developing countries: a study of its contribution to the performance of health financing systems. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 2005. 10(8): p. 799-811.

- Ensor, T., A. Hossain, and N. Miller, Funding health care in Bangladesh–assessing the impact of new and existing financing. facilities, 1998.

- Akin, J.S., N. Birdsall, and D.M. De Ferranti, Financing health services in developing countries: an agenda for reform. Vol. 34. 1987: World Bank Publications.

- Rahman, H., Structural adjustment and macroeconomic performance in Bangladesh in the 1980s. The Bangladesh Development Studies, 1992: p. 89-125.

- Mustafa, A. and T. Begum, Universal Health Coverage Assessment People’s Republic of Bangladesh. 2014.

- Ahmad, A., Provision of Primary Healthcare Services in urban areas of Bangladesh: the case of urban primary healthcare project. Working Papers, Department of Economics, Lund University, 2007(9).

- Ensor, T., et al., Geographic resource allocation in Bangladesh. Health Policy Research in South Asia, 2003: p. 101.

- Rahman, R.M., Human rights, health and the state in Bangladesh. BMC international health and human rights, 2006. 6(1): p. 4.

- http://www.dhakatribune.com/business/2014/sep/04/adb-344-gdp-investment-needed-reach-growth-target.

- Lewis, M., Informal payments and the financing of health care in developing and transition countries. Health Affairs, 2007. 26(4): p. 984-997.

- Khan, A.R. and B. Sen, Inequality and its sources in Bangladesh, 1991/92 to 1995/96: an analysis based on household expenditure surveys. The Bangladesh Development Studies, 2001: p. 1-49.

- Buse, K. and C. Gwin, The World Bank and global cooperation in health: the case of Bangladesh. The Lancet, 1998. 351(9103): p. 665-669.

- http://www.heu.gov.bd/index.php/resource-tracking/bangladesh-national-health-accounts.html.

- Adams, A.M., et al., Innovation for universal health coverage in Bangladesh: a call to action. The Lancet, 2014. 382(9910): p. 2104-2111.

- Lester, R., Eco-economy: building an economy for the earth. 2002: Orient Blackswan.

- Hoque, Z. and T. Hopper, Political and industrial relations turbulence, competition and budgeting in the nationalised jute mills of Bangladesh. Accounting and Business Research, 1997. 27(2): p. 125-143.

- Ensor, T. and S. Cooper, Overcoming barriers to health service access: influencing the demand side. Health policy and planning, 2004. 19(2): p. 69-79.

- Mondal, M.A.H., L.M. Kamp, and N.I. Pachova, Drivers, barriers, and strategies for implementation of renewable energy technologies in rural areas in Bangladesh—An innovation system analysis. Energy Policy, 2010. 38(8): p. 4626-4634.

- Baqui, A.H., et al., Effect of timing of first postnatal care home visit on neonatal mortality in Bangladesh: a observational cohort study. Bmj, 2009. 339.

- Thornalley, P.J., et al., High prevalence of low plasma thiamine concentration in diabetes linked to a marker of vascular disease. Diabetologia, 2007. 50(10): p. 2164-2170.

- Creese, A.L., User charges for health care: a review of recent experience. Health policy and planning, 1991. 6(4): p. 309-319.

- Islam, A. and T. Biswas, Health System Bottlenecks in Achieving Maternal and Child Health-Related Millennium Development Goals: Major Findings from District Level in Bangladesh.

- Islam, A. and T. Biswas, Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases and the Healthcare System in Bangladesh: Current Status and Way Forward. Chronic Dis Int, 2014. 1(2): p. 6.

- Islam, A. and T. Biswas, Health System in Bangladesh: Challenges and Opportunities. American Journal of Health Research, 2014. 2(6): p. 366-374.

- TANJILA TASKIN, T.B., ALI TANWEER SIDDIQUEE, ANWAR ISLAM, AND DEWAN ALAM, Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases among the Elderly in Bangladesh Old Age Homes. 2014. 3(4).