Stress Coping Styles Moderating the Relationship Between Job Stress and Deviant Behaviors: Some Gender Discriminations

Mohsen Golparvar*, Mohsen Taleb, Fahimeh Abdoli, Hassan Abedini

Department of I/O Psychology, Psychology and Educational College, Islamic Azad University, Esfahan (Khorasgan) Branch, Esfahan, Iran

Abstract

Coping styles are the important and effective factors on employees’ behavior in organizations. According to the moderating role of efficient and inefficient coping styles, the main purpose of this research was to study the role of job stress on deviant behaviors. The research sample group consisted of three hundred eighty teachers (192 male and 188 female) in Esfahan, Iran. The results of hierarchical regression analysis revealed that efficient coping styles moderates marginally the relationship between enterprise and challenging stress with deviant behaviors toward individuals. Further analysis revealed that only for women, efficient coping styles moderates the relationship between enterprise and challenging stress with deviant behaviors toward individuals. That is, in high efficient coping styles, there is a positive and significant relationship between enterprise stress and deviant behaviors toward individuals, but in low efficient coping styles, rather than in high efficient coping styles, there is a stranger relationship between challenge stress and deviant behaviors toward individuals.

Keywords

Coping Stress, Deviant Behaviors, Stress Coping Styles, Gender Discrimination, Iran

Received:April 11, 2015

Accepted: April 29, 2015

Published online: June 23, 2015

@ 2015 The Authors. Published by American Institute of Science. This Open Access article is under the CC BY-NC license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

1. Introduction

Job stress is a relatively common phenomenon in many workplaces which in many forms negatively affects peoples’ well-being and health (Harris, Harvey & Kacmar, 2009; Yang, Hongsheng & Spector, 2008). Among the most important factors that cause stress, role ambiguity, role conflict, overload, conflicting relationships with colleagues and supervisor and the lack of balance between job sources and job demands can be mentioned (Gilboa, Shirom, Fried & Cooper, 2008). One prominent variable as a direct and indirect outcome of job stress is deviant behaviors (Golparvar, Kamkar & Javadian, 2012). Deviant behaviors are opposite acceptable behavior (based on rules, customs, norms) in the organization that include the formats such as theft, damage to facilities and equipment, misbehaving with colleagues and customers, impolite non-verbal behavior, gossiping, work-to-rule, not pre-arranged absenteeism and tardiness (Appelbaum, Iaconi & Matousek, 2007). When these behaviors target the organization and its benefits, they are called deviant behaviors toward organization and when they target the individuals, they are called deviant behaviors toward individuals (Georges, 2009; O'Brien, 2008; Robinson, 2008). Theoretical explanation and relatively strong evidence of the relationship between job stress and deviant behaviors have been presented by theoreticians and researchers from different countries (Appelbaum et al, 2007; Ersoy, 2010; Podsakoff, LePine & LePine, 2007).

1.1. Job Stress and Deviant Behaviors

Theoretical explanations and several mechanisms have so far been presented on how stress in workplace relates with deviant behaviors. One of these theoretical approaches is stress- non-equilibrium- compensation approach (Golparvar & Hosseinzadeh, 2011; Golparvar, Nayeri & Mahdad, 2009; Golparvar et al, 2012). Stress - non equilibrium approach, historically, is rooted in classic theories of stress and excitement domain. However, classic approaches regarding creating non-equilibrium states by stress were mostly limited to physiological reactions and general behaviors (Cooper, Dewe & O’Driscoll, 2001; Dewe, O’Driscoll & Cooper, 2012). This approach, being expanded to explicit compensation behaviors (returning balance by positive and negative behaviors) in workplace has became a humanitarian approach with certain assumptions (Golparvar et al, 2012). Based on stress- non-equilibrium- compensation approach, one of the individuals’ important reactions to stressors is the disruption in their cognitive, emotional and behavioral balance. This non-equilibrium state has a motivational nature and forces the individual to compensate; that is, returning to the lost balance (Golparvar et al, 2009; Golparvar & Hosseinzadeh, 2011; Golparvar et al, 2012).

If the stress continues in this compensation, the individual decreases the level of positive behaviors and consequently resort to negative behaviors based on their mental, motivational and personality preparations (Golparvar et al, 2009; Golparvar & Hosseinzadeh, 2011). In this regard, based on previous researches and also based on evidence obtained from certain working environments in Iran, stress causes negative emotional states in individuals and toward working tasks, and leads them in a voluntary-compulsory form toward unethical and deviant behaviors by making emotional, behavioral and cognitive imbalance in individuals (Golparvar et al, 2012). In fact, it seems that when people experience stress, they tend to show deviant behaviors in an emotional behavioral alignment to compensate the assumed created imbalance because this stress mostly brings negative emotional states. Align with above mentioned explanations, research evidence supports the relationship between job stress and deviant behaviors (Akinbode, 2009; Anwar, Sarwar, Awan & Arif, 2011; Bayram, Gursakal & Bilgel, 2009; Fagbohungbe, Akinbode & Ayodeji, 2012; Hauge, Skogstad & Einarsen, 2007; Mayer, Thau, Workman, Van Dijke & De Cremer, 2012;Omar, Halim, Zainah, Farhadi, Nasir et al, 2012).

Podsakoff et al (2007) in a meta-analysis concluded that hindrance stress has a positive relationship with job turnover and withdrawal behaviors and in contrast, challenging stress has a negative relationship with these behaviors. Fagbohungbe et al (2012) showed besides other variables, work overload is among the predictors of deviant behaviors in the workplace. Omar et al (2012) showed that job stress and job satisfaction are the predictors of deviant behaviors. Besides the findings of previous studies, what is very important is that there are variables that based on stress- non-equilibrium- compensation approach could make changes in the relationship chain between stress and deviant behaviors (Golparvar et al, 2009; Golparvar & Hosseinzadeh, 2011). Based on the mentioned approach, when a variable or some variables have a significant capacity in accelerating or preventing the non-equilibrium process, they can affect the relationship chain and the disrupting role of stress balance and the consequent next behaviors (Golparvar et al, 2012). One of the variables in this domain is the coping style.

1.2. Stress Coping Styles, Job Stress and Deviant Behaviors

Coping styles are active or passive efforts to respond to the circumstances and situations that create stress, to avoid or reduce stress and include problem focused style (efficient styles) and emotion focused style (inefficient styles) (Daniels, Beesley, Cheyne, & Wimalasiri, 2008; Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004). Problem focused styles include methods such as ‘problem solving’ (that means a set of semi-centralized ideas or efforts with stressors in addition to using analytical approach to solve the problem), ‘positive reappraisal’ (that include efforts to make positive concepts in dealing with problems), ‘taking responsibility’ (that include a series of reactions that are based on accepting one’s role in making the problem and result in constructive and continuous effort in correcting the situation), and finally it includes ‘social support seeking’ (Cooper, 2010; Dewe, O’Driscoll & Folkman, 2011; Ramos, 2011).

In contrast, emotion focused styles, that is, direct confrontation (a series of aggressive and direct behaviors with stress causing problems in order to immediately change the stress source), self restraint or suppression (avoiding the stress source) and denial (denying the stress making situations) include passive (inefficient styles) coping styles (Brown, Westbrook & Challagalla, 2005; Dewe et al, 2010, 2012). Efficient coping styles have a negative relationship with perceived stress level and in contrast, inefficient coping styles have a positive relationship with the perceived stress (Fortes-Ferreira,Peiro, Gonzalez-Morales & Martin, 2006; Guppy & Weatherstone, 1997; Li & Yang, 2009). Theoretically, the role of coping styles in decreasing or increasing the stress is related to the role of these styles in removing or not removing the stress source (Moneta & Spada, 2009). This means that if the coping style (efficient) eliminates or reduces the stress source, naturally individual’s stress level will decrease, but if coping style (inefficient) cannot eliminate the stress source, the stress level not only will not reduce but also it might increase (Park, 2007; Pearsall, Ellis & Steinm, 2009; Stetz, Stetz, & Bliese, 2006).

Moreover, some evidence indicates that stress coping styles are related to individuals’ behavior and attitudes in the workplace (Zhao & Yamaguchi, 2008; Newness, 2011). However, the relationship between coping styles and employees’ attitude and behavior in workplace is directly investigated only in few studies to date. Rick and Guppy (1994) stated that withdrawal (inefficient) coping styles are related to the feeling of being under pressure, lower job satisfaction and lower mental health. Guppy & Weatherstone (1997) studied coping styles, inefficient attitudes and well being of the employers and showed that withdrawal coping (an inefficient and negative) is related to a lower well being and the problem focused coping style is related to a more favorable mental health.

Stajkovic & Luthans (1998) in a meta-analysis regarding the relationship between self efficacy (related positively with efficient coping styles) and work related performance, has presented a mean effect size of 0.35. Fortes-Ferreira et al (2006) investigated the direct and indirect and palliative coping styles on the relationship between job stress and well being. Results showed that the interaction of direct coping methods (positive and efficient) with job stress was not significant in predicting individuals’ well being. In contrast, the interaction between inefficient coping styles with job stress was significant in predicting physical complaints. In Fortes-Ferreira et al (2006) study, the interaction of two inefficient and efficient styles was significant in predicting physical complains and mental problems. In a study by Zhaoand Yamaguchi (2008) it was shown that emotion focused coping style moderates the relationship between job stress and job satisfaction, but in contrast, problem focused coping style moderates the interpersonal stress and job satisfaction relationship.

1.3. Research Conceptual Model

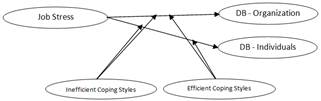

Figure 1. Research Conceptual Model.

In general, there are no studies on the moderating role of coping styles regarding stress and deviant behavior, so few predictions are proposed based on stated assumptions on stress- non-equilibrium- compensation approach and are tested in this study. The first prediction is that it is expected that positive coping styles remove the stressor-induced pressure as a set of positive behavior skills, return non-equilibrium induced by stress to the balanced state by providing opportunities for them, and prevent deviant behaviors. In contrast, it is predicted that inefficient coping styles might be a basis for strengthening the non equilibrium state due to stress and consequently either increase the level of deviant behaviors or make them sustain. The relationships and theoretical predictions mentioned in this research were examined. Research conceptual model presented in figure 1.

1.4. Research Hypotheses

H1. There is a positive significant relationship between job stress and deviant behaviors (toward organization and toward individuals).

H2. There is a positive and negative significant relationship between inefficient and efficient coping styles and job stress respectively.

H3. There is a positive and negative significant relationship between inefficient and efficient coping styles and deviant behaviors (toward organization and toward individuals) respectively.

H4. Inefficient and efficient coping styles moderate the relationship between job stress (enterprise, interpersonal and challenging job stress) and deviant behaviors (toward organization and toward individuals). That is, there is different relationship between job stress (enterprise, interpersonal and challenging job stress) and deviant behaviors (toward organization and toward individuals) in low and high levels of inefficient and efficient coping styles.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

The research method was descriptive-correlation and its statistical population is consisted of male and female teachers (1000 persons) in Esfahan, Iran (autumn, 2012). From this statistical population and based on Krejcie & Morgan’s (1970) sample size table, four hundred teachers were selected as a sample to participate in this research. They were selected by multistage sampling and through the schools at six regions of teaching and training in Esfahan, Iran. After collecting questionnaires, twenty questionnaires (about %5) were excluded due to failure to respond. Therefore, the sample group reduced to three hundred eighty teachers (192 male, 188 female). From two hundred forty eight teachers who declared their age, %6.6 had thirty years old, %32.6 had thirty one to forty years old, and %32.9 had forty one to fifty years old, and % 2.6 had fifty one and above years old. From two hundred seventeen teachers who declared their teaching experience, %23.7 had to ten years teaching experience, %18.2 had eleven to twenty years teaching experience, and %13.3 had twenty one to thirty years teaching experience. Majority of teachers were married (%72.4), %62.1 had bachelor or master degree. The average age of participants was 37.51 years (with a standard deviation of 7.12 years) and the average work experience of the sample members was 11.96 (with a standard deviation of 7.08 years).

2.2. Measures

Job Stress: Job stress was measured with the forty one item scale adapted from Zhao and Yamaguchi (2008). The scale measures three job stress dimensions; enterprise stress (twenty one items, an example item is: the future of my work is not bright), interpersonal stress (ten items, an example item is: there is a lack of team--spirit among teachers), and challenge stress (ten items, an example item is: my work responsibility is high). In this scale, responses are given along a 5-point scale from 1= strongly disagree to 5= strongly agree. Zhao and Yamaguchi (2008) along with face and content validity of this scale, demonstrated construct validity of this scale through exploratory factor analysis. Cronbach’s alpha for the three subscales of this questionnaire (enterprise stress, interpersonal stress, and challenge stress) were .9, .81, and .73 respectively (Zhao & Yamaguchi, 2008). In current research factor analysis demonstrated construct validity of this scale (KMO= .93, Bartlett’s test of Sphericity= 8500.49, p<.001, factor loadings ranging from .4 to .8, for three subscales). Cronbach’s alpha for the enterprise stress, interpersonal stress, and challenge stress were .91, .84, and .84 respectively.

Deviant Behaviors: Deviant behaviors were measured with using fifty items which adapted from Bennett and Robinson (2000). This scale has been translated and validated in Iranian work settings in the previous research (Golparvar et al, 2012), and assessed deviant behaviors toward organization (eight items) and toward individuals (seven items). Respondents were asked to indicate how often they engaged in activities such as staying home instead going to work and saying I was sick. Responses were rated on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (often). Previous research suggested that the Iranian version of the deviant behaviors questionnaire had a good construct and concurrent validity (Golparvar et al, 2012). The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of this questionnaire in present study for deviant behaviors toward organization and toward individuals were 0.91 and .88 respectively.

Stress Coping Styles: Coping styles were measured using thirteen items adapted from Park (2007). This questionnaire measures two job stress coping styles; negative (inefficient) coping behaviors (eight items, an example item is: when I encounter with job stress, avoid being with people), and positive (efficient) coping behaviors (five items, an example item is: when I encounter with job stress, try to solve the problem). In this scale, responses are given along a 4-point scale from 1= never to 4= always. The reliability and validity of the scale have been demonstrated in previous studies (Park, 2007). For instance, Park (2007) reported Cronbach's alpha of the negative (inefficient) coping behaviors, and positive (efficient) coping behaviors equal to .6 and .51 respectively. In this study also exploratory factor analysis (Varimax rotation and factor loading the minimum of 0.4) was carried out to test construct validity of the scale (KMO= .86, Bartlett’s test of Sphericity= 3573.82, p<.001). Reliability of the scale through Cronbach's alpha in current research for negative (inefficient) coping behaviors, and positive (efficient) coping behaviors were .71 and .6 respectively.

3. Results

Data were analyzed with SPSS-18 to compute correlations, descriptive statistics and hierarchical regression analysis. Out of the total responses, missing values were less than 0.15 percent, which replaced with the average of each variables mean in database. As suggested in the literature (Aiken & West, 1991), a three-stage hierarchical moderated regression analysis was used to test the forth research hypothesis (H4, about the moderating effects of efficient and inefficient coping styles in the relationship between job stress (enterprise stress, interpersonal stress, and challenge stress) and deviant behaviors). According to Cohen, Cohen, West and Aiken (2003) recommendation for moderated regression analysis with interaction terms, all the variables centralized and then entered in the regression equation. The forth hypothesis (H4) was tested by examining the significance of the interaction terms and the F-ratio associated with the variations in ∆R2of the equations in the Model 3. Means, standard deviations and correlations among all research variables are presented in table 1.

As shown in Table 1, there are positive significant relationships between job stress dimensions and deviant behaviors toward organization (r=.24. r=.25, and r=.25, p<.01 respectively), and deviant behaviors toward individuals (r=.15, r=.19, and r=.19, p<.01 respectively). Therefore H1 (there is a positive significant relationship between job stress and deviant behaviors (toward organization and toward individuals)) has been supported completely. Also, enterprise stress (r = -.17, p<.05), interpersonal stress (r = -.26, p<.01), challenging stress (r = -.17, p<.01) related negatively to efficient coping styles, and only interpersonal stress (r =.14, p<.05) related positively to inefficient coping styles. Therefore H2 (there is a positive and negative significant relationship between inefficient and efficient coping styles and job stress respectively) has been supported partially. As shown in Table 1, deviant behavior toward organization (r = -.24, p<.01), and deviant behavior toward individuals (r = -.26, p<.01), related negatively to efficient coping styles, but deviant behaviors toward organization (r =.15, p<.01), and deviant behaviors toward individuals (r =.28, p<.01) related positively to inefficient coping styles. Therefore H3 (there is a positive and negative significant relationship between inefficient and efficient coping styles and deviant behaviors (toward organization and toward individuals, respectively)) has been supported completely. The results of hierarchical regression analysis for deviant behaviors are shown in table 2.

Table 1. Means, standard deviation and inter-correlations between research variables.

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Efficient coping styles | 3.06 | .5 | (.7) | ||||||

| Inefficient coping styles | 2.26 | .53 | -.12* | (.71) | |||||

| Enterprise stress | 2.9 | .63 | -.17** | .04 | (.91) | ||||

| Interpersonal stress | 2.77 | .64 | -.26** | .14* | .7** | (.84) | |||

| Challenging stress | 2.87 | .66 | -.17** | .1 | .69** | .7** | (.84) | ||

| DB- toward organization | 1.6 | .73 | -.24** | .15** | .24** | .25** | .25** | (.91) | |

| DB- toward individuals | 1.44 | .61 | -.26** | .28** | .15** | .19** | .19** | .69** | (.88) |

Note: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, Alpha coefficients presented on diagonal.

Table 2. Hierarchical moderated regression analysis of job stress, coping styles and deviant behaviors.

| DB- toward organization | DB-toward individuals | |||||

| Model1 | Model2 | Model3 | Model1 | Model2 | Model3 | |

| β | β | β | β | β | β | |

| Enterprise stress | .06 | .1 | .1 | -.05 | -.03 | -.02 |

| Interpersonal stress | .13 | .01 | .01 | .14 | -.02 | -.01 |

| Challenge stress | .09 | .11 | .1 | .11 | .12 | .16 |

| Efficient coping styles | - | -.19** | -.19** | - | -.21** | -.21** |

| Inefficient coping styles | - | .11* | .11* | - | .25** | .25** |

| Enterprise stress × Efficient coping styles | - | - | -.01 | - | - | -.19‡ |

| Interpersonal stress × Efficient coping styles | - | - | .03 | - | - | .05 |

| Challenging stress × Efficient coping styles | - | - | -.09 | - | - | -.25** |

| Enterprise stress × Inefficient coping styles | - | - | -.03 | - | - | -.06 |

| Interpersonal stress × Inefficient coping styles | - | - | .03 | - | - | .004 |

| Challenging stress × Inefficient coping styles | - | - | .03 | - | - | .02 |

| R2 or DR2 | .07** | .048** | .008 | .041** | .106** | .025† |

| F or DF | 9.42** | 10.06** | .55 | 5.31** | 23.23** | 1.83 |

Note: *p<.05; **p<0.01, †p≤.09 ‡p≤.07, Model1 = main effects of job stress dimensions, Model2 = main effect of coping styles, and Model3 = interactive

effects of job stress dimensions and coping styles.

As could be seen in table 2, in model 1, job stress dimensions were entered as predictors of deviant behaviors (toward organization and toward individuals). In model 2, the coping styles were entered as predictor of deviant behaviors (toward organization and toward individuals). In model 3, the interaction between job stress dimensions and coping styles was entered. As shown in Table 2, job stress dimensions are not related significantly to deviant behaviors toward organization. In model 2 (Table 2), efficient and inefficient coping styles are related significantly to deviant behaviors toward organization (β= -.19, p<.01, β=.11, p<.05 respectively). In model 3, our results (Table 2) revealed that efficient and inefficient coping styles has not been moderates the relationship between job stress dimensions and deviant behaviors toward organization. As could be seen in table 2, for deviant behaviors toward individuals, job stress dimensions are not related significantly to deviant behaviors toward individuals. In model 2 (Table 2), efficient and inefficient coping styles are related significantly to deviant behaviors toward individuals (β= -.21, β=.25, p<.01 respectively). In model 3, our results (Table 2) revealed that efficient coping styles has been marginally moderates the relationship between enterprise stress (β= -.19, p= .07), and challenging stress (β= -.25, p<.001) with deviant behaviors toward individuals (DR2 = 0.025, DF = 1.83, and p= .09). To clarifying the exact form of the interactions, a separate moderated hierarchical regression was conducted for men and women teachers. The results of moderated hierarchical regression analysis (for men and women about deviant behaviors toward individuals) presented in table 3.

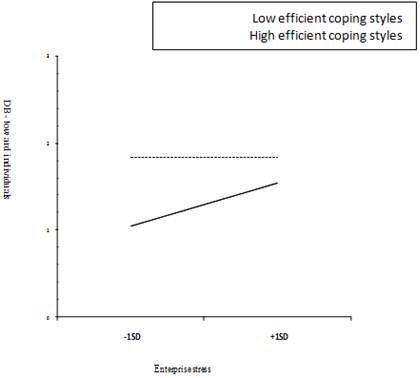

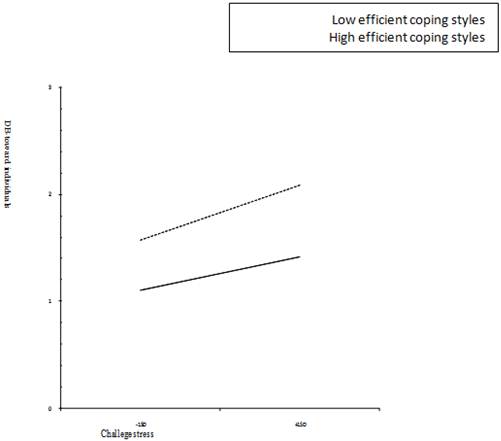

As shown in table 3, only for women, in model 3, our results (Table 3) revealed that efficient coping styles has been moderates the relationship between enterprise stress (β=.33, p<.05), and challenging stress (β= -.49, p<.001) with deviant behaviors toward individuals (DR2 = 0.068, DF = 2.64, and p<.05). To clarifying and detecting the form of the interactions for women, the equation at the high and low level of efficient coping styles (one standard deviation above the mean or + 1SD, and one standard deviation below the mean or – 1SD) was computed. Figure 2 and 3 present the results of simple slope analysis.

Table 3. Hierarchical moderated regression analysis of job stress, coping styles and deviant behaviors toward individuals for men and women.

| Deviant behaviors toward individuals | ||||||

| Men teachers | Women teachers | |||||

| Model1 | Model2 | Model3 | Model1 | Model2 | Model3 | |

| β | β | β | β | β | β | |

| Enterprise stress | -.002 | .1 | .04 | -.1 | -.007 | -.02 |

| Interpersonal stress | .2 | .001 | .06 | .03 | -.1 | -.11 |

| Challenge stress | -.006 | .05 | .07 | .28 | .21 | .2 |

| Efficient coping styles | - | -.22** | -.22** | - | -.17* | -.14 |

| Inefficient coping styles | - | .21** | .21** | - | .31** | .34** |

| Enterprise stress × Efficient coping styles | - | - | .09 | - | - | .33* |

| Interpersonal stress × Efficient coping styles | - | - | .07 | - | - | .17 |

| Challenging stress × Efficient coping styles | - | - | -.17 | - | - | -.49** |

| Enterprise stress × Inefficient coping styles | - | - | -.02 | - | - | .09 |

| Interpersonal stress × Inefficient coping styles | - | - | .12 | - | - | -.06 |

| Challenging stress × Inefficient coping styles | - | - | -.06 | - | - | .1 |

| R2 or DR2 | .039 | .093** | .012 | .051* | .129** | .068 |

| F or DF | 2.57 | 9.94** | .42 | 3.31* | 14.28** | 2. 64* |

Note: *p<.05; **p<0.01, Model1 = main effects of job stress dimensions, Model2 = main effect of coping styles, and Model3 = interactive effects of job stress dimensions and coping styles.

Figure 2. Simple slopes of enterprise stress on deviant behaviors toward individuals for low and high efficient coping styles (for women).

As it can be seen in figure 2, in high efficient coping styles, rather than in low efficient coping styles, there is a stronger positive relationship between enterprise stress and deviant behaviors toward individuals among women.

As it can be seen in figure 3, in low efficient coping styles group rather than in high efficient coping styles group, there is a stronger positive relationship between challenging stress and deviant behaviors toward individuals among women.

4. Discussion

This study was conducted to investigate the moderating role of efficient and inefficient coping styles regarding job stress and deviant behaviors relationship. Firstly, the results showed that efficient coping style was negatively related to deviant behaviors toward organization and individuals (colleagues) and in contrast inefficient coping style is positively related to deviant behaviors toward organization and individuals (colleagues). This finding shows an implicit consistency with the reported findings by other researchers who showed that efficient and inefficient (positive and negative) coping styles are related to behaviors and attitudes at workplace (Daniels et al, 2008). Moreover, the relationship of efficient and inefficient coping styles with deviant behaviors is in line with the proposed ideas regarding the roles and proposed consequences for problem focused (efficient) and emotion focused (inefficient) coping styles (Newness, 2011; Zhao & Yamaguchi, 2008).

Figure 3. Simple slopes of challenging stress on deviant behaviors toward individuals for low and high efficient coping styles (for women).

To explain this section of findings, it should be stated that in problem focused styles (efficient), people follow approaches such as problem solving, positive reappraisal of problems and difficulties, taking responsibility and seeking social support to alleviate the pressure (Fortes-Ferreira et al, 2006; Guppy & Weatherstone, 1997; Li & Yang, 2009). In these approaches, people do not follow behaviors that might hurt themselves and others in workplaces. Therefore, this explanation reveals that efficient coping styles are not in line with deviant behaviors toward individual and organization in terms of functional orientation. Furthermore, the negative relationship of efficient coping style with deviant behaviors toward individual and organization causes the assumption that deviant behaviors themselves are among inefficient coping styles. This explanation is implicit in the positive relationship of inefficient coping styles with deviant behaviors toward individual and organization. Finally, there is a significant consistency between the acquired relationships among efficient and inefficient coping styles with deviant behaviors in the present study, considering the deviant behaviors as compensation behaviors to change the stress-induced non-equilibrium state to equilibrium state.

Based on stress – non-equilibrium – compensation approach, deviant behaviors are the consequence of non-equilibrium cognitive, emotional and behavioral state in individuals which aim to moderate stress and return to the equilibrium (health and well-being) state (Golparvar er al, 2009; Golparvar & Hosseinzadeh, 2011; Golparvar et al, 2012). This explanation has proposed a different view (in terms of humanistic emphasis on voluntary compulsory deviant behaviors) compared to what is already in the literature (despite its long history in the field of humans’ emotional and behavioral response to stress). Based on what is explained, it seems that in many situations, people unwillingly, due to lack of efficient coping ability and due to an imposed working situation which is full of unfair stressors, might have to resort to doing deviant behaviors (Golparvar et al, 2012). Undoubtedly, such an approach (stress- non equilibrium- compensation) is not seeking confirmation for doing deviant behaviors in workplaces (especially) due to high stress and the like. But such a view emphasizes the compulsory voluntary nature of these behaviors which are they contradictory, and seeks indirect interventions to control and manage the deviant behaviors. For example, instead of identifying and dealing with deviant behaviors in the workplace, we can reduce them by identifying effective factors associated with these behaviors such as efficient coping behaviors without infringing people’s dignity and status.

The forth hypothesis (H4) of the study was confirmed in that efficient and inefficient coping styles are not able to moderate the relationship between any job stress dimensions with deviant behaviors toward the organization but, efficient coping styles only for women moderates the relationship between enterprise stress and the challenging stress with the deviant behaviors toward individuals. The first important point in the present study is the lack of moderating role of efficient and inefficient styles regarding the relationship between job stress dimensions and deviant behaviors toward organization. The first explanation is about the nature of teaching and the organizational structure of the educational system. Teaching is primarily considered as a holy profession with religious orientations and sublime values. From this perspective, teachers, even when under pressure, believe that God bestows the real valuable rewards of their attempts and pressures, and should try not to do anything against the education organization even secretly so their reward will not be nullified. The second explanation in this regard is related to the organizational structure of the educational system and how the teacher’s performances are. In most organizations, people are directly present in their workplace and work there. In these kinds of organizations, people might more easily resort to do deviant behaviors toward organization due to work load because they are present and have direct interaction with their organization. However, most teachers are present at school, which takes a subsidiary role compared to the central organizations, and communicate less with the respective organization. This less direct contact probably provides less chance of performing deviant behaviors toward the organization. If this is true, future researches might need to investigate the deviant behaviors toward schools instead of deviant behaviors toward organizations. In addition, educated people including teachers, feel embarrassed to report negative coping behaviors because such behaviors are a kind of weakness and disability.

Another important point, as shown in this research, only for women, when efficient coping is at a high level, the increase of enterprise stress sharply result in deviant behaviors toward individuals (colleagues), but when efficient coping is at a low level, there in not significant relationship between enterprise stress and deviant behaviors toward individuals. This finding somehow is not consistent with the predictions of stress-non equilibrium- compensation approach (that is efficient coping styles, as a set of positive behavior skills, alleviate the stressor-induced pressure through set of positive behavior skills, and returns non-equilibrium induced by stress to the balanced state by providing opportunities for them, and prevent deviant behaviors).

Indeed, according to the stress non-equilibrium-compensation approach, it was expected that when the efficient coping techniques are high, the increase in any kind of stress should not lead to a higher deviant behaviors (such deviant behaviors focused on individuals and organizations) (Golparvar er al, 2009; Golparvar & Hosseinzadeh, 2011; Golparvar et al, 2012). Several reasons can cause this result. First, efficient copings among specific jobs (such as teaching) and in special forms of stress (such as enterprise stress), may be at deviant behaviors toward individuals’ service (and not organizations). In this explanation, pointing out to the special forms of stress is because of a condition which was expected for challenging stress. It means that in low efficient coping, there was a stronger relationship between challenging stress and deviant behaviors focused on individuals. Therefore, one of the possibilities of misbehaving both individuals and colleagues is that teachers in encountering stress, despite having the ability of efficient coping, due to transferring anger, have the most same-level relationship with their colleagues in the workplace. The second reason about this finding which completes the first explanation is that sex is a higher-order moderating variable after efficient coping styles, that its moderating role in the relationship between stress coping styles and deviant behaviors has been less attended. It is likely that enterprise stress in women, despite their ability of efficient coping, would be lead to the increase of deviant behaviors toward individuals (colleagues). Although the logic of such a relationship is not clearly specified, it may happen because of women’s wider relationship with their colleagues in the workplace rather than men. For this reason, in encountering enterprise stress, women unintentionally transfer a part of their work pressure to their colleagues through deviant behaviors toward individuals. This finding also shows that the rate of proximity, despite high efficient coping, is a factor which causes a serious relationship between enterprise stress and deviant behaviors toward individuals.

Beside provided explanations about the moderating role of efficient coping styles in the relationship between enterprise stress and deviant behaviors toward individuals, the relationship between challenging stress and deviant behaviors toward individuals, along with moderating role of efficient coping styles, there are some tips which should be considered. The first point is that some researchers such as Podsakoff et al (2007) reported a negative relationship between challenging stress and organization turnover and withdrawal behaviors in their meta-analysis. This means the increase in challenging stress decreases the tendency to turnover and withdrawal behaviors. Such a finding implies that challenging stress is a kind of positive job stress. In the mentioned study, the moderating role of coping styles regarding the challenging stress with deviant behaviors is not directly and clearly mentioned. However, Podsakoff et al (2007) findings are not in line with what is shown in figure 3 in the present study (regarding the fact that challenging stress among women teachers is positively related to deviant behaviors toward individuals). This finding might imply the message that challenging stress does not have a relatively positive aspect in all the situations and all working groups. Yet, this finding might be related to a special sample group such as teachers which will be considered in the following discussion.

The final point about the forth hypothesis (H4), is that efficient coping style did not moderate the relationship between interpersonal stress with the deviant behaviors toward individuals. This lack of moderation is far beyond expectation, since interpersonal stress (especially between colleagues) is also in line with deviant behaviors toward individuals. Theoretical reasons for this issue is not clear yet, but maybe teachers generally do not face as much problem in interpersonal stress as they face problems in challenging and enterprise stress (the reported means in table 1 show that challenging stress and enterprise stress are somehow more than interpersonal stress).

5. Conclusion

Preliminary, the results of this research can in some ways play a role in increasing the current our knowledge and understanding. First, the results of current research showed that maybe the high efficient coping would not be always lead to the reduction or elimination of the relationship between stress and deviant behaviors toward individuals. Indeed, it is likely that when individuals cannot act deviant behaviors toward organizations and because of proximity and the interpersonal relationships between colleagues, even in high efficient coping, the stress leads to high deviant behaviors toward individuals. The next role of this research is that kinds of stress can affect the role of high efficient coping. It means that when enterprise stress rather than challenging stress is being raised, high efficient coping will show distinct roles. The final point which should be considered for future researches is related to the role of sex and the relationship between styles of work stress and deviant behaviors. There is a possibility that sex in mentioned relationships, after styles of coping, is a higher order moderating variable. It is recommended that interested researchers repeat this study with behaviors other than deviant behaviors. Moreover, it is useful to repeat this study in men and women teacher groups and the moderating patterns of coping styles be compared and explained for each sex in relation to job stress and deviant behaviors.

Implications and Limitations

The most important and applicable suggestion for the present research (on the basis of simple correlations) is related to the positive coping roles in self moderation of deviant behaviors as well as management and control of these behaviors. It would be useful that during in service education, by using experienced and professional teachers, training of effective and efficient coping be carried out for teachers beside other educational programs. Moreover, it is suggested that in case of observing deviant behaviors from some teachers, prior to any confrontation or decision, their stress level and their positive coping ability be considered. This research has some limitations. The first limitation in the present study is that the sample group for the present study is teachers; therefore it is logical that precautions be made in generalizing the results to other working groups. Secondly, this is a correlation study and no cause and effect impressions could be made on its findings. Thirdly, deviant behaviors and coping styles (especially the negative ones) are evaluated based on self report. This method could be accompanied by social favorable self presentation which needs to be taken into consideration.

References

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S.G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Akinbode, G. A. (2009). Effects of gender and organizational factors on workplace deviant andfraudulentbehaviors. Journal of Management and Entrepreneur, 2 (1), 53-79.

- Anwar, M.N., Sarwar, M., Awan, R.N., & Arif, M.I. (2011). Gender differences in workplace deviant behaviorof university teachers and modification techniques. International Education Studies, 4 (1), 193-197.

- Appelbaum, S. H., Iaconi, G. D., & Matousek, A. (2007). Positive and negative deviant workplace behaviors: causes, impacts, and solutions. Corporate Governance, 7 (5), 586-598.

- Bayram, N., Gursakal, N., & Bilgel, N. (2009). Counterproductive work behavior among white-collar employees: A study from Turkey. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 17 (2), 180–188.

- Bennett, R.J., & Robinson, S. L. (2000). Development of a measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 349-360.

- Brown, S. P., Westbrook, R. A., & Challagalla, G. (2005). Good cope, bad cope: Adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies following a critical negative work event. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90 (4), 792-798.

- Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S.G., & Aiken, L.S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/ correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd ed, Mahwah, NJ; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

- Cooper, C. L., Dewe, P., & O’Driscoll, M. (2001). Organizational stress: A review and critique of theory, research, and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Daniels, K., Beesley, N., Cheyne, A., & Wimalasiri, V. (2008). Coping processes linking the demands-control-support model, affect and risky decisions at work. Human Relations, 61(6), 845–874.

- Dewe, P., O’Driscoll, M., & Cooper, C. (2010). Coping with work stress: A review and critique. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Dewe. P. J., O’Driscoll, M. P., & Cooper, C. L. (2012). Theories of psychological stress at work. In R.J. Gatchel & I.Z. Schultz (Eds.), Handbook of occupational health and wellness (pp. 23-38). New York: Springer Science and Business Media.

- Ersoy, N. C. (2010). Organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior: Cross-cultural comparison between Turkey and the Netherlands. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Erasmus University.

- Fagbohungbe, B.O., Akinbode, G.A., & Ayodeji, F. (2012). Organizational determinants of workplace deviant behaviors: An empirical analysis in Nigeria.International Journal of Business and Management, 7(5), 207-221.

- Folkman, S. (2011). Stress, health, and coping: Synthesis, commentary, and future directions. In S. Folkman (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of stress, health, and coping (pp. 453–462). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Folkman, S., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2004). Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(6), 745–774.

- Fortes-Ferreira ,L., Peiro, J. M., Gonzalez-Morales, G.M., & Martin, I. (2006). Work-related stress and well-being: The roles of direct action coping and palliative coping. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 47(4), 293-302.

- Georges, S. (2009). Deviant behavior and violence in Luxembourg schools. International Journal of Violence and School, 4(10), 54-70.

- Gilboa, S., Shirom, A., Fried, Y., & Cooper, C. (2008). A meta-analysis of work demandstressors and job performance: Examining main and moderating effects.Personnel Psychology, 61 (2), 227-271.

- Golparvar, M., & Hosseinzadeh, K.H. (2011). Model of relation between person job none fit with emotional exhaustion and desire to leave work: Evidence for the stress –non equilibrium – compensation model. Quarterly Journal of Applied Psychology, 20 (1/17), 41-56.

- Golparvar, M., Kamkar, M., & Javadian, Z. (2012). Moderating effects of job stress in emotional exhaustion and feeling of energy relationships with positive and negative behaviors: job stress multiple functions approach. International Journal of Psychological Studies, 4(4), 99- 112.

- Golparvar, M., Nayeri, S., & Mehdad, A. (2009). The relationship between stress, emotional exhaustion andorganizational deviant behavior in Zoob Ahan Stock Company: Evidences for model of stress–exhaustion (none equilibrium)-compensation. Journal of New Findings in Psychology, 1 (8), 19-34.

- Guppy, A., & Weatherstone, L. (1997). Coping strategies, dysfunctional attitudes and psychological well-being in white collar public sector employees. Work & Stress: An International Journal of Work, Health & Organizations, 11(1), 58-67.

- Harris, K. J., Harvey, P., & Kacmar, K. M. (2009). Do social stressors impact everyone equally? An examination of the moderating impact of core self-evaluations. Journal of Business Psychology, 24(2), 153-164.

- Hauge, L. J., Skogstad, A., & Einarsen, S. (2007). Relationships between stressful work environments and bullying: Results of a large representative study. Work & Stress, 21(3), 220- 242.

- Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607-610.

- Li, M., & Yang, Y. (2009). Determinants of problem-solving, social support seeking, andavoidance: A path analytic model. International Journal of Stress Management,16(3), 155-176.

- Mayer, D. M.,Thau, S.,Workman, K. M.,Van Dijke, M., &De Cremer, D. (2012). Leader mistreatment, employee hostility, and deviant behaviors: Integrating self-uncertainty and thwarted needs perspectives on deviance.Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 117(1), 24-40.

- Moneta, G. B., & Spada, M. M. (2009).Coping as a mediator of the relationship between trait intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and approaches to studying during academic exam preparation. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(5/6), 664-669.

- Newness, K. A. (2011). Stress and coping style: An extension to the transactional cognitive-appraisal model. Unpublished Master Thesis in Psychology, Florida International University.

- O'Brien, K. E. (2008). A stressor-strain model of organizational citizenship behavior andcounterproductive work behavior. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Department of Psychology, College of Arts and Sciences, University of South Florida.

- Omar, F., Halim, F.W., Zainah, A. Z., Farhadi, R., Nasir, R., Khairudin, R. (2012). Stress and job satisfaction as antecedents of workplace deviant behavior. World Applied Science Journal. 12(Special Issue), 46-51.

- Park, J. (2007). Work stress and job performance. Perspectives on Labour and Income, 8(12), 5–17.

- Pearsall, M. J., Ellis, A. P. J., & Steinm J. H. (2009). Coping with challenge and hindrance stressors in teams: Behavioral, cognitive, and affective outcomes. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 109(1), 18-28.

- Podsakoff, N. P., LePine, J. A., & LePine, M. A. (2007). Differential challenge stressor hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 435-454.

- Ramos, J. A. (2011). A comparison of perceived stress levels and coping styles of non-traditional graduate students in distance learning versus on-campus programs. Contemporary Educational Technology, 2(4), 282-293.

- Rick, J., & Guppy, A. (1994). Coping strategies and mental health in white collar public sector employees. European Work and Organizational Psychologist, 4(2), 121-137.

- Robinson, S. L. (2008). Dysfunctional workplace behavior. In J. Barling. & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational behavior (pp. 141−159).Thousand Oaks,CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Shields, M. (2006). Stress and depression in the employed population. Health Reports, 17(4), 11-29.

- Stajkovic, A. D., & Luthans, F. (1998). Self-efficacy and work-related performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 124(2), 240-261.

- Stetz, T. A., Stetz, M. C., & Bliese, P. D. (2006).The importance of self-efficacy in themoderating effects of social support on stressor-strain relationships. Work andStress, 20 (1), 49-59.

- Yang, L.-Q., Hongsheng, C., & Spector, P. E. (2008). Job stress and well-being: An examination from the view of person-environment fit. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 81(3), 567–587.

- Zhao, D.M., & Yamaguchi, H. (2008). Relationship of challenge and hindrance stress with coping style and job satisfaction in Chinese state-owned enterprises. Japanese Journal of Interpersonal and Social Psychology, 8, 77-87.