Tourism Planning and Development for Sustainability in Kenya’s Western Tourism Circuit

John Paul Onyango1, *, Margaret Kaseje2

1Hospitality and Tourism Department, Great Lakes University of Kisumu, Kisumu City, Kenya

2Dean Faculty Arts and Science, Great Lakes University of Kisumu, Kisumu City, Kenya

Abstract

The secret to success in both the expansion of international hotel chains and the initial positive results from eco-hospitality by the end of the 1980s was due to the application of the fundamental principles of tourism planning and development which stresses on involvement of key stakeholders in the planning process. Hotel administrations that are concerned with ecology must plan and take action towards preserving the environment by collaborating with communities and key stakeholders. These include the entire hotel operations and related establishments, along with employees at all levels, investors, architects, engineers, ecologists, and others who are interested in preserving nature. Governments and organizations engaged in tourism need to work together to guarantee that tourism is planned, developed and regulated in order to control its impact on nature and to maintain natural resources. This paper explores the main components of tourism planning and development processes, starting from the nature of planning, the various planning approaches and the ways that these broad approaches are implemented, and ends with a review of the outputs and outcomes in Kenya’s Tourism in the Western Circuit. Emerging from gaps identified in the study, a tourism planning and development model is proposed that planners and investors can use for evaluating whether or not the objectives of tourism and its sustainability have been achieved.

Keywords

Tourism Planning, Stakeholder Involvement, Eco-Hospitality, Sustainability

Received:April 9, 2015

Accepted: May 13, 2015

Published online: June 12, 2015

@ 2015 The Authors. Published by American Institute of Science. This Open Access article is under the CC BY-NC license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

1. Introduction

Tourism provides a major economic development opportunity for many countries and a means of improving the livelihoods of its residents. Western Kenyan region is not an exception. Both the public and private sectors involved in tourism depend on planning to achieve sustainable tourism development that respects the local community, creates appropriate employment, maintains the natural environment, and delivers a quality visitor experience. However, many tourism destinations have pursued development without proper planning and without considering the many impacts such development brings to the community.

Western Kenya is an area of great geographic, cultural and natural diversity, offering tourists just as much, if not more, than many of Kenya’s better known tourist areas. Most travelers dream of finding a new and unknown destination, somewhere far from the beaten tourist path, where the thrill of real discovery and exploration reward the visitor with new and unexpected experiences, sights and sound. Scenic areas include; Lake Victoria, Kakamega Forest Reserve, Kit Mikaye, Rusinga Island, Ruma National Park,Ndere island National Park, Western Highlands – Kisii, Kericho – World’s finest quality teas, World’s finest Athletes and Impala Park among others.

Planning involves setting and meeting objectives. Early tourism research (Ogilvie, 1933) into the outcomes of tourism planning was restricted primarily to the measurement of the economic impacts for destination areas, due to the ease with which economic impacts may be measured, compared to environmental and social impacts. (Mathieson et al, 1982, Archer et al 1998). In order to maximize economic benefits many governments allowed the private sector to take important decisions about tourism development in an unrestricted and unplanned way (Hawkins, 1992). However, the focus of the private sector and tourism planning was naturally oriented toward short-term economic gains, through the construction of facilities which attract foreign visitors. As a result, too little attention was paid to socio-cultural effects on host communities and environmental problems for receiving destinations, which in the long-term, may outweigh the benefits (Seth, 1985; Jenkins, 1994).

This paper explores the main components of tourism planning and development processes, starting from the nature of planning, the various planning approaches and the ways that these broad approaches are implemented, and ends with a review of the outputs and outcomes in Kenya’s Tourism in the Western Circuit. A tourism planning and development model is proposed that planners and investors can use for evaluating whether or not the objectives of tourism and its sustainability have been achieved

1.1. Statement of the Problem

Many tourism destinations in the region have pursued development without proper planning and without considering the many impacts such development brings to the community. Unrestrained tourism developments have diminished the image of many destinations, to the extent that they attract only low-spending mass tourism. As a result, serious socio-economic and environmental problems have emerged. Since tourism activity relies on the protection of environmental and socio-cultural resources for the attraction of tourists, planning is an essential activity for the success of a destination.

1.2. Purpose of the Study and Objectives

Although various approaches have been developed in general planning, a literature review of tourism shows that not many authors have been concerned with tourism planning. Akehurst (1998) explains this by the fact that plans are developed by consultancy firms that rarely publish or divulge their results.

This paper explores the main components of tourism planning and development processes, starting from the nature of planning, the various planning approaches and the ways that these broad approaches are implemented, and ends with a review of the outputs and outcomes in Kenya’s Tourism in the Western Circuit aiming to enable all the stake holders embrace tourism planning principles.

2. Literature Review

Simpson (2009, p. 186) notes that "a key challenge in sustainable tourism is to develop economically viable enterprises that provide livelihood benefits to local communities while protecting indigenous cultures and environments". Indeed, the inability of local communities to fully participate and genuinely benefit from tourism is identified as the major reason for the unsustainable development of tourism (Jithendram & Baum, 2000). Surely then tourism can only be considered ‘successful’ when it serves the actual needs and demands of the local population, and importantly, provides equitable socio-economic returns.

Gunn (1979) was one of the first to define tourism planning as a tool for destination area development, and to view it as a means for assessing the needs of a tourist receiving destination. According to Gunn (1994) the focus of planning is mainly to generate income and employment, and ensure resource conservation and traveler satisfaction. Specifically, through planning under- or low-developed destinations can receive guidelines for further tourism development. Meanwhile, for already developed countries, planning can be used as a means "to revitalize the tourism sector and maintain its future viability" (WTO, 1994, p.3). To this end, Spanoudis (1982) proposes that: Tourism planning must always proceed within the framework of an overall plan for the development of an area’s total resources; and local conditions and demands must be satisfied before any other considerations are met (p.314). Every development process starts with the recognition by local/central government, in consultation with the private and public sector, that tourism is a desirable development option to be expanded in a planned manner.

2.1. Development Plans for Tourism

In order to successfully design a development plan, it is necessary to have a clear understanding of the development objectives to be achieved at national, regional or local levels. According to Sharpley and Sharpley (1997), these objectives are: A statement of the desired outcomes of developing tourism in a destination and may include a wide range of aims, such as job creation, economic diversification, the support of public services, the conservation or redevelopment of traditional buildings and, of course, the provision of recreational opportunities for tourists (p.116). The nature of these objectives depends on national, regional and local preferences grounded in the country’s scale of political, socio-cultural, environmental and economic values, as well as its stage of development. Development objectives may be: political, such as enhancing national prestige and gaining international exposure; socio-cultural, the encouragement of activities that have the potential for the advancement of the social and cultural values and resources of the area and its traditions and lifestyles; environmental, e.g. control of pollution; and economic, such as increasing employment and real incomes.

On the other hand, objectives can represent a combination of political, socio-cultural, environmental and economic aims, although they should take into consideration the desires and needs of the local community in order to retain its support. Unfortunately, objectives are often in conflict with each other and cannot all realistically be achieved (WTO, 1994). For example, if the two main objectives of a government are to achieve spatial distribution of tourism activity and increase tourist expenditure, these objectives are opposed, since to increase tourism expenditure, tourists should be attracted to the capital or the largest cities of the country, where more alternatives for spending exist, e.g. in entertainment and shopping. Therefore, Haywood (1988) proposes that the choice of objectives will have to be limited to those aspirations which the industry is capable of meeting or are the most appropriate to serve. Early tourism research (Ogilvie, 1933; Alexander, 1953) into the outcomes of tourism planning was restricted primarily to the measurement of the economic impacts for destination areas, due to the ease with which economic impacts may be measured, compared to environmental and social impacts. In order to maximize economic benefits many governments allowed the private sector to take important decisions about tourism development in an unrestricted and unplanned way (Hawkins, 1992). However, the focus of the private sector and tourism planning was naturally oriented toward short-term economic gains, through the construction of facilities which attract foreign visitors. As a result, too little attention was paid to socio-cultural effects on host communities and environmental problems for receiving destinations, which in the long-term, may outweigh the benefits (Seth, 1985; Jenkins, 1994).

2.2. Boosterism

A major tradition to tourism planning, and as Hall (2000) debated it as a form of non-planning, is ‘boosterism’. According to the ‘boosterism’ approach, tourism is beneficial for a destination and its inhabitants when environmental objects are promoted as assets in order to stimulate market interest and increase economic benefits, while barriers to development are reduced. As Page (1995) remarked "local residents are not included in most planning processes and the carrying capacity of the region is not given adequate consideration". As a result, this approach does not provide a sustainable solution to development and is practiced only by "politicians who philosophically or pragmatically believe that economic growth is always to be promoted, and by others who will gain financially by tourism" (Getz, 1987, p.10). As a result, tourism evolution brings many problems to the local community, which includes overcrowding, traffic congestion, superstructures, and socio-cultural deterioration. Most of these problems can be attributed to laissez-faire tourism policies and insufficient planning (Edgell, 1990). Although some destinations have benefited from tourism development without any ‘conscious’ planning, the majority suffer from inattentive planning (Mill and Morrison, 1985). This is evidenced by the inconsistent growth in the tourism industry in the Kenyan Western circuit.

2.3. Conventional Planning

Although the majority of countries have prepared tourism development plans, most of these plans are not implemented, and others are only "partially or very partially implemented" (Baud-Bovy, 1982, p.308). This may be due to ‘conventional planning’ as defined by Gunn (1988), that "has too often been oriented only to a plan, too vague and all encompassing, reactive, sporadic, divorced from budgets and extraneous data producing". Therefore all tourism development plans should go through careful analysis, selection of the choice after environmental scanning and finally laying out frameworks for implementation strategies.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

The researchers used a survey research design because it best served to answer the questions and the purposes of the study. The survey research is one in which a group of people or items are studied by collecting and analyzing data from only a few people or items considered to be representative of the entire group. In other words, only a part of the population is studied, and findings from this are expected to be generalized to the entire population (Nworgu 1991:68). Similarly, McBurney (1994:170) defines a survey that assesses public opinion or individual characteristics through the use of a questionnaires and sampling methods. This method was used by much of the previous research in similar areas (e.g. Ghobadian et. al., 2008; Elbanna, 2010; Aldehayyat, 2011). The study involved collecting data from 31 hospitality outlets including hotels, travel companies and visitor attractions in western Kenya region. In each outlet, one respondent at the managerial level was chosen for the study. The sample size was arrived at using Yamane (1967) sample size formula. Interviews were conducted from sampled firms and where possible focused group discussions were held.

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

The environmental conservation projects in absolute terms were taken for purposes of this study. It was felt that environmental conservation projects would give more meaning because the interest of the researchers was to see whether there was environmental conservation consciousness as a result of embracing tourism planning.

To gather data for this study, a range for absolute values was used to capture tourism outcomes. The outcome was the key dependent variable in this study and both the direct and indirect dimensions were examined. Three direct outcome indicators were used to measure the planning and development of the hospitality outlets. These were: direct economic outcomes, direct environmental outcomes, and direct socio-cultural outcomes. Respondents were asked to indicate the band where their respective outlets fall on each of the indicators. The banding of the direct measures was harmonized with the indirect measures in an effort to provide an indication of overall outcomes. This was also aimed at facilitating analysis. A six-point Likert scale captured the direct outcome indicators, that is, the extent of any environmental conservation that arose as a result of embracing tourism planning and development. The means and standard deviations were based on responses of those interviewed where they indicated the bands where their outlets fell regarding tourism planning as measured in the three direct outcome indicators. Within the bands, 0 represented the lowest band and 5 represented the highest band.

The pre-testing of the questionnaire indicated that respondents were more willing to indicate the range where their respective outlets fell on the indicators, as opposed to stating the absolute values. After the pilot testing on 10 respondents and necessary modifications, the revised questionnaire was administered to 31 purposively selected respondents that formed the sample for the study. All the 31 questionnaires given out were successfully completed and returned. The data collected from the field was analyzed and a statistically weighted mean was used in answering the research questions.

4. Results

4.1. Tourism Outcomes for Hospitality Outlets

There was a high mean outcome on the economic indicator compared to environmental and socio-cultural outcomes. From the table 1 below, economic outcome had a mean of 3.451 followed by environmental impact at 1.838 and finally social cultural outcomes at 0.93. There were great variations across the outlets on realization of environmental and socio-cultural outcomes as compared to the economic ratio.

Table 1. Comparative analysis of Tourism Outcomes on Hospitality Outlets.

| Tourism Outcomes | n | Mean | Standard Deviation |

| Environmental | 31 | 1.838 | 1.067 |

| Economic | 31 | 3.451 | 0.767 |

| Socio-cultural | 31 | .903 | 1.106 |

4.2. Relationship Between Tourism Planning and Sustainability of Outlets

As an additional ingredient to the previous studies on the relationship between tourism planning and the outlets’ sustainability, indirect indicators were of interest in this study. The indicators used in this study were: creation of job opportunities, environmental conservation projects within the community, promotion of cultural practices and adherence to legislative polices. Respondents were asked to indicate on a six point Likert type scale the performance of their respective outlets on each of these indicators.

Of those who responded, 3.2% indicated that creation of job opportunities within their outlets had improved to a small extent, 35.5% indicated that this had improved averagely in their outlets; another 35.5% indicated that this had improved to a large extent while 25.8 % indicated that it had improved to a very large extent. This gave a mean score of 3.8 out of a possible maximum 5 points, implying that majority of the outlets surveyed improved to a great extent in terms of creation of job opportunities to the residents.

4.3. Growth of Environmental Conservation in Outlets

Responses indicated that 22.6% of the firms achieved a very small growth in environmental conservation, 32.3% achieved a small growth, 22.6% achieved average growth, and 6.5% realized such growth to a large extent, while 12.9% realized growth to a very large extent.

4.4. Promotion of Cultural Practices by Outlets

A six point Likert scale was used to capture data on promotion of cultural practices. The interest of the researcher was to establish extent to which the outlets if any have been promoting cultural practices.

Of those who responded, 3.2% indicated that no cultural promotion had been practiced in their outlets, while 9.7% indicated that this has been practiced to a very small extent in their firms. About a third (35.5%) indicated that cultural promotion had been practiced to a small extent in their firms, another 35.5% indicated that cultural promotion had been practiced somehow in their outlets, 12.9% indicated that cultural promotion had been practiced in their outlets to a large extent while only 3.2% had practiced the cultural promotion to a very large extent.

4.5. Adherence to Legislative Policies by Outlets

The extent to which target firms had observed legislative policies was examined. As for previous indirect outcome indicators; a six point Likert scale was used. Of the firms that responded, 9.7% had adhered to a very small extent, 32.3% had conformed to legislative policies to a small extent, 29% had achieved this averagely, and 25.8% had achieved this to a large extent, while only 3.2% had attained full approval of operation to a very large extent.

4.6. Indirect Tourism Outcomes in Hospitality Outlets

Findings indicate that hospitality outlets have performed better on creation of job opportunities with a mean score of 3.838 and standard deviation of 0.86 (Table 2). The responses also reveal greater variation across the outlets in terms of level of realization of indirect outcome indicators.

Table 2. Comparative analysis of Indirect Tourism Outcomes by Hospitality Outlets.

| Outcome Indicators | n | Mean | Standard Deviation |

| Job opportunities to residents | 31 | 3.838 | 0.860 |

| Environmental conservation projects | 31 | 2.452 | 0.362 |

| Cultural promotion | 31 | 2.548 | 1.059 |

5. Discussions

The findings from the study conducted indicate that most hospitality outlets in the Western Tourism circuit focus on job creation for the residents as opposed to an all-inclusive approach to ensure economic, environmental, and socio cultural outcomes for sustainability. Economic factors are priority. This focus may compromise the quality of the environment and accelerate socio-cultural erosion. The dynamic nature of the industry, the severity of the consequences of incompatible development and the potential for environmental and social benefits from planned development demand that governments, the tourism industry and all stakeholders assume proactive roles and implement a mix of management strategies to shape and guide the industry in an environmentally suitable manner.

In guiding tourism development, few outlets are able to observe legislative policies; therefore self-regulation is likely to be more effective than statutory regulation because the industry is more likely to take the responsibility and ownership for self-regulatory approaches. Competition among outlets is likely to reinforce self-regulation.

Overall, the outlets did well on the indirect tourism outcome indicators as opposed to the direct outcome indicators as a result of embracing tourism planning.

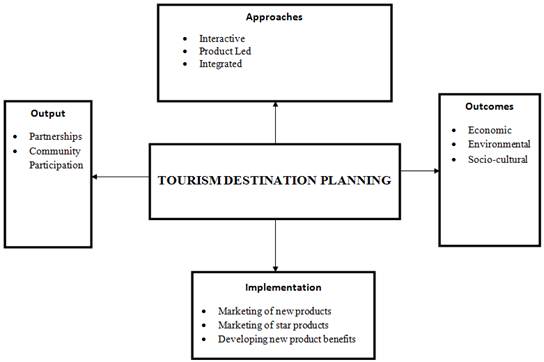

Figure 1. A Model for Tourism Planning and Development.

[Adapted from: Andriotis K (2007). A Framework for the Tourism Planning Process. Kanishka publishers, New Delhi].

Onyango, JP, and Kaseje, M. Great Lakes University of Kisumu, 2014.

6. Recommendations and Conclusions

Due to the gaps identified in this study regarding tourism planning and development for sustainability, the researchers for this study propose the following model (Figure 1) advanced from Andriotis (2007) to be practiced by the outlets in Western Kenya in stimulating a coordinated approach towards tourism planning and development. The model proposes the essential components of interactive, product-led and integrated approaches for effective tourism planning hence achieving socio-economic and environmental benefits through developing and marketing of new products.

6.1. Interactive Planning

Rather than conventional planning, Gunn (1994) proposes interactive planning, Bramwell and Sharman (1999) suggest collaborative planning and Timothy (1998; 1999) recommends co-operative and participatory planning, all directed along the same lines, where there is incorporation of the local community’s opinions and desires in the planning process. This approach to planning leads to better decisions that are reached through a participative process, even though it is far more difficult. This shift in emphasis does not mean that research and concepts by professional planners are abandoned. Rather, it means that many other constituencies, other than planners, have experiences, opinions and constructive recommendations as well. Final decisions have a much better chance of being implemented if publics have been involved (Gunn, 1994, p.20). As a result, interactive planning proposes top-down, together with bottom-up input, for better implementation of tourism development plans.

6.2. Product-Led Planning

Braddon (1982) proposes that tourism planning should be "market oriented, providing the right product for the consumer - the tourist" (p.246). Inskeep (1991) states: A completely market-led approach provides whether attractions, facilities, and services the tourist market may demand could result in environmental degradation and loss of socio-cultural integrity of the tourist area, even though it brings short term economic benefits (p.30).

Therefore, he proposes that in order to avoid this situation a ‘product led approach’ is more applicable. This approach is also mentioned by Baud-Bovy and Lawson (1977) with their "product analysis sequence for outdoor leisure planning" (PALSOP) where emphasis is put on the ‘product’. According to Inskeep (1991) the product-led approach implies that "only those types of attractions, facilities, and services that the area believes can best be integrated with minimum impacts into the local development patterns and society are provided, and marketing is done to attract only those tourists who find this product of interest to them (p.30). This practice ensures appreciation of the product qualities by the tourist for sustainability.

6.3. Integrated Planning

Simpson, M.C 2009 and Gunn (1994) agree with Inskeep (1991) that only integrated planning can reassure communities that the type of development results will be appropriate for them. Therefore, Baud-Bovy (1982) declares "Any tourism development plan has to be integrated into the nation’s socioeconomic and political policies, into the natural and man-made environment, into the socio-cultural traditions, into the many related sectors of the economy and its financial schemes, and into the international tourism market" (p.308). Tourism planners should learn from mistakes made elsewhere and realize that the planning process is not a static but a continuous process which has to integrate ‘exogenous changes and additional information’ (de Kadt, 1979; Baud-Bovy, 1982; Gunn, 1994; Hall, 2000). Consequently, tourism planning should be flexible and adaptable to cope with rapidly changing conditions and situations faced by a community (Atach-Rosch, 1984; Choy, 1991). Nevertheless, many decision makers and developers are often located at a very considerable distance from the destination under development which means that they may be unaware of, or unconcerned about any costs resulting from tourism development (Butler, 1993b).

As Gunn (1988) remarks, planning is predicting and "it requires some estimated perception of the future. Absence of planning or short-range planning that does not anticipate a future can result in serious malfunctions and inefficiencies" (p.15). Therefore, Wilkinson (1997b) proposed that strategic thinking should be incorporated into planning as this will guide tourism development through careful selection of strategic options for implementation.

6.4. Market and Product Strategic Options

Empirical studies of general planning practices have presented a wide variety of popular planning tools and techniques for the fulfilment of development objectives, using various market/product strategic options. (UNTWO 2013) The development and promotion of the region’s brand image and range of products in order to meet the needs of the market is vital to the competitiveness of the tourism sector. This is about raising awareness and attracting interest but also about increasing the length of stay and level of spending from visitors and encouraging repeat visits and recommendations.

Defining and articulating a distinctive brand for the region is the key to effective marketing, providing the basis for promotional messages and guiding product development so that it can deliver on the brand promise. The brand, which is far more than a logo or slogan, sums up the whole competitive identity of a destination, representing its core essence and enduring characteristics. Brand development should be based on consultation with local stakeholders and be well informed by market research.

A well-developed marketing plan should be a key component of a region’s tourism strategy. It should stem from the careful selection of target markets based on product strengths, current performance and global trends. A well-resourced and coordinated program of promotional activity should be supported by the government and private sector, using a range of communication techniques. Tourism products should be of the quality and variety to attract and retain the target markets. A problem in many developing countries and regions is the lack of consistency in product quality, which can affect competitiveness. This may be helped by having effective systems for setting, inspecting and reporting quality standards, such as hotel classification systems or tour guide standards and licensing. These systems in turn can point to where investment is needed and encourage businesses to respond. Product development, innovation and diversification should be fully informed by an understanding of market trends and the current strengths and weaknesses of the existing product portfolio. This should link to strategies and actions to guide and stimulate investment.

A number of authors share similar views on market and product strategic options and propose alternatives on how a firm (or destination) can achieve leadership in the market through competitive advantages. For the achievement of this, strategists suggest a type of differentiation or leadership. Ansoff (1965) views differentiation as new products for new markets and Henderson (1979) suggests differentiation through products with high market share in a fast growing market (star products). Gilbert (1990) proposes a move from a position of commodity to a position of a status area, through the development of tourism product benefits, while Porter (1980) proposes the attainment of leadership through three angles: low-cost, differentiation and focus strategy.

If a destination promotes and sells new or existing quality products to new or existing environmentally-friendly markets, it may pass from a position of commodity to a position of status which may be achieved through an improved image which may attract higher spending and loyal customers. This market may respect the environment and the host society’s welfare and may bring more benefits than costs to the destination. Thus, demand may not be incidental, but intentional. This can be achieved only if development is planned and not occasional.

‘Star product destinations’ should have a high market share, but they should not exceed the carrying capacity of the destination and destroy local resources. An increase in the number of visitors does not always mean benefits for the destination. Higher spending visitors may bring better results.

The above-mentioned strategies of new products for new markets, marketing of star products and developing tourism product benefits can be used by developers as tools for the formulation of planning approaches and for the enhancement of their strategic decisions. The essence of strategy formulation is an assessment of whether the destination is doing the right thing and how it can act more effectively. In other words, objectives and strategies should be consciously developed so that the destination knows where it wants to go. To this end, strategy formulation should be carried out with the involvement of the community, so as to ensure their help for the achievement of the plans. In summary, not all destinations will be in the position to expand or achieve sustainability in the future. Only the destinations that choose the best strategies may be reinforced with a competitive advantage that will bring them the most benefits from tourism development.

6.5. Partnerships in Tourism Planning

In the tourism industry, there are examples where partnership arrangements are highly effective for the success of tourism planning and development. Since the public sector is concerned with the provision of services, the resolving of land-use conflicts and the formulation and implementation of development policies, and the private sector is mainly concerned with profit. Partnerships between the private and public sector on various issues can benefit destinations (Sharpley, 2002). As Timothy (1998) highlights: Co-operation between the private and the public sector is vital ... a type of symbiotic relationship between the two sectors exists in most destinations (since) public sector is dependent on private investors to provide services and to finance, at least in part, the construction of tourism facilities. Conversely, without co-operation, tourism development programs may be stalled, since private investors require government approval of, and support for, most projects (p.56).

6.6. Community Participation in Tourism Planning

Community involvement in tourism can be viewed from two perspectives namely; in the benefits of tourism development and in the decision-making process (McIntosh et al, 1986; Timothy, 1999; Tosun, 2000). For residents to receive benefits from tourism development "they must be given opportunities to participate in, and gain financially from, tourism" (Timothy, 1999, p.375, Butcher, 2008). However, benefits from tourism are often concentrated in the hands of a limited number of people who have the capital to invest in tourism at the expense of other segments of the community (e.g. lower class, uneducated and poor people). Therefore, Vivian (1992) finds many traditional societies repressive since they often exclude large numbers of people from the development and planning process. As a result, Brohman (1996, p.59) proposes that tourism benefits and costs should be distributed more equally within the local community, allowing a larger proportion of the local population to benefit from tourism expansion, rather than merely bearing the burden of its costs. Pearce et al. (1996) have seen community participation from the aspect of involving: individuals within a tourism-orientated community in the decision-making and implementation process with regard to major manifestations of political and socioeconomic activities (p.181). Potter et al. (1999, p.177) refer to the term of empowerment as "something more than involvement" and Craig and Mayo (1995) suggest that through empowerment the ‘poorest of the poor’ may be included in decision-making. According to Potter (1999): Empowerment entails creating power among local communities through consciousness raising, education and the promotion of an understanding within communities of the sources of local disenfranchisement and of the actions they may take. It may also involve the transfer of power from one group, such as the controlling authority, to another (p.178).

Community support of tourism projects is crucial and will depend upon the extent to which it disturbs or enhances the livelihoods of the local residents and their environment. It is therefore important to be responsive to the needs of the local community and to earn their confidence to generate a positive attitude towards the project. The developers must seek to ensure community participation and community benefits and establish mutually beneficial relationships with the local community and liaison with local environmental groups

6.7. Economic Measures

A review of tourism studies shows that development is mainly associated with economic prosperity. Therefore, the most frequently used measures in tourism research have been concerned with the economic impacts. Frechtling (1994a, p.359) asserted that tourism economic potential can be understood as the gross increase in the income of people located in an area, usually measured in monetary terms, and the changes in incomes that may occur in the absence of the tourism activity. Measures dealing with the direct benefits of tourism include labour earnings, business receipts, number of jobs, and tax revenue (Frechtling, 1994b). The focus of tourism economic research is based on the measurement of the economic benefits of tourism to communities. The concept of the multiplier analysis is based upon the recognition that the tourism impact is not restricted in the initial consumption of goods and services but also arises through the calculation of the direct and secondary effects created by additional tourism expenditure within the economy. There are four different types of tourism multipliers application in common use (Jackson, 1986; Fletcher and Archer, 1991): sales (or transactions), output, income and employment. The extent of the multiplier depends on the size, structure and diversity of the local economy.

6.8. Environmental Measures

In an attempt to eliminate environmental costs, many countries have included in their legislation Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for all projects, including tourism. The aim is to predict the environmental consequences of a proposed development activity, and to ensure that potential risks are foreseen and necessary measures to avoid, mitigate or compensate for environmental damage are identified (Green and Hunter, 1993). A variety of other indicators can be used, often included in EIA procedure, to measure environmental impacts such as climate change, urban environmental quality, natural resources, eutrophication, acidification, toxic contamination, waste, energy and transport indicators. Corporate policies reflecting a high level of commitment to environmental management, including strategies to effectively limit social and environmental impacts both in short-term as well as in long term and to ensure equitable sharing of benefits among the community, are of central importance. Strategies to comply with national regulations, development plans and national environmental standards must be adopted. In addition, the industry is encouraged to adopt self-regulatory techniques and voluntary management procedures such as environmental guidelines and codes of conduct rather than be strictly regulated. (Blanke, J., and Chiesa T. (ed.) 2013), developing and fostering more varied forms of travel can transform environmental sustainability from a regulatory burden to a true differentiator for tourism source markets. Policymakers, especially those in developing tourism destinations, should prioritize long-term sustainability to safeguard their natural and cultural assets because "green consumerism" has become a significant buying power in developed markets. Key emerging tourist groups, including the well travelled retiring baby boomers, are demanding green travel offerings instead of traditional sun-and-beach vacations. A clear focus on greening the supply side of tourism as well as environmental conservation efforts on a national level will generate clear advantages over competing destinations. Policymakers need to be able to consistently match long-term tourism master planning, short-term interests of multiple stakeholders, and external influences such as macroeconomic events or tourist demand changes to make tourism sustainable economically and environmentally. To succeed, policymakers will need to manage the bottleneck of natural assets carefully to put economic yield and ecological footprint into a steady, stable state.

The outlets must therefore ensure; Contribution towards the preservation and conservation of the environment, Consciousness in education toward conservation in Hospitality industry, Efficiency in the consumption of energy, water, and waste, and lastly Eco-Hospitality marketing practices.

6.9. Social Measures

According to Cooper et al. (1998, p.180) the socio-cultural impacts of tourism are the most difficult to measure and quantify, because they are often highly qualitative and subjective in nature. There are two key methods for collecting information for social impact measurement: primary research through surveys or interviews including attitudinal surveys, the Delphi technique and participant observation and the analysis of secondary sources found in government records, public documents and newspapers. These impacts are on the other hand very important and must be considered as they provide a sense of belonging and involvement to the local community

In conclusion, tourism development therefore has both positive and negative effects on a tourism destination. Communities are very often threatened with unwanted developments and face problems from unplanned or carelessly planned tourism expansion. To overcome these multi-faceted problems, comprehensive tourism plan is needed to maximize the benefits and minimize the costs or disadvantages of development through the involvement of the local community who must live with the tourists and the costs and benefits they bring.

It is therefore important to examine existing destination marketing and tourism development planning in the context of the challenges of a more volatile macroeconomic environment. Established destinations need to pool their efforts on innovations, multi-stakeholder cooperation, and flexibility if they are to respond successfully to demand from emerging regions. Developing destinations in the region should consider effective short-term turn around strategies to strengthen their sectors and re-establish their attraction for the international traveler by focusing on long-term sector development and making sustainability a core of destination development and marketing. Despite increasing instability induced by economic, political, and environmental challenges, tourism is expected to remain a significant driver of future economic growth.

References

- Aldehayyat, J. (2011). Organizational characteristics and the practice of strategic planning in Jordanian hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, vol. 30 No. 1, 192-199. ISSN (Paper) 0278-4319

- Andriotis K (2007). A framework for the Tourism Planning Process. Kanishka publishers, New Delhi.

- Ansoff, H. I. (1965). Corporate Strategy: An Analytical Approach to Business Growth & Expansion. New York McGraw–Hill.

- Atach-Rosch, I. (1984) Public Planning for Tourism: A General Method for Establishing Economic, Environmental, Social and Administrative Criteria. PhD thesis. Washington, University of Washington.

- Baud-Bovy, M. (1982) New concepts in planning for tourism and recreation. Tourism Management. 3(4), pp.308-313.

- Baud-Bovy, M. and Lawson, F. (1977) Tourism and Recreation: A Handbook of Physical Planning. Boston: CBI.

- Blanke, J., and Chiesa T. (ed.) (2013) The Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report 2013: Reducing barriers to economic growth and job creation. World Economic Forum (WEF), Geneva. Available at < http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TT_Competitiveness_Report_2013.pdf>

- Bramwell, B. and Sharman, A. (1999) Collaboration in local tourism policymaking. Annals of Tourism Research. 26(2), pp.392-415

- Butcher, J. (2008). The Myth of Agency through Community Participation in Ecotourism. In P. Burns & M. Novelli (Eds.), Tourism Development: Growth, Myths and Inequalities (pp. 11-27). Wallingford: CABI.

- de Boer, W. (1993) Introduction to the round table on planning sustainable tourism development. In: WTO (ed) Round Table on Planning Sustainable Tourism Development. 10th General Assembly, Bali 30 September - 9 October. Madrid: World Tourism Organisation, pp.1-12.

- Elbanna, S. (2010). Strategic planning in the United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Commerce and social sciences.

- Getz D. (1986), Models in Tourism planning: Towards Integration of Theory and Practice

- Ghobadian, A., O’Regan, N., Thomas, H., & Liu, J. (2008). Formal strategic planning, operating environment,

- Green, H. and C. Hunter. (1993) "The Environmental Impact Assessment of Tourism Development." London. Mansell Publishing limited.

- Gunn (1979). Tourism planning. Crane Russak & Company, Inc., 3 East 44th Street, New York, N.Y. 10017. 1979. 371p

- Hall, C.M. (2000) Tourism Planning: Policies, Processes and Relationships. Essex: Prentice Hall.

- Hawkins, R. (1992) The Planning and Management of Tourism in Europe: Case Studies of Planning, Management and Control in the Coastal Zone. PhD Thesis. Bournemouth: Bournemouth University.

- Haywood, K.M. (1988) Responsible and responsive tourism planning in the community. Tourism Management. 9(2), pp.105-116

- Inskeep, E. (1991). Tourism planning: An integrated and Sustainable Development Approach. New York.Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- Jenkins, J. (1993) Tourism policy in rural New South Wales Policy and research priorities. Geojournal. 29(3), pp.281-290

- Jithendram, K., & Baum, T. (2000). Human Resource Development and Sustainability: The Case of India. International Journal of Tourism Research, 2(6), 403-436.

- Murphy, P.E and Andresser, (1998). Tourism planning and development on Vancouver Island: An assessment of the core periphery model: Professional geographer, 40 (1): 32-42

- Nworgu, B.G. (1991). Education research: Basic issues and methodology. Ibadan: Wisdom

- Pearce, D.G. (1995) Planning for tourism in the 1990s: An integrated, dynamic, multiscale approach. In: Butler, R.W. and Pearce, D.G. (eds) Change in Tourism: People, Places, Processes. London: Routledge, pp.229-244.

- Reddy, M. V., and Wilkes, K. (ed.) (2014) Tourism in the Green Economy. Routledge (forthcoming)

- Sharpley, R. (2002). Tourism: A Vehicle for Development? In R. Sharpley & D. J. Telfer (Eds.), Tourism and Development: Concepts and Issues (pp. 11-34). Buffalo: Channel View Publications.

- Simpson, M. C. (2009). An Integrated Approach to Assess the Impacts of Tourism on Community Development and Sustainable Livelihoods. Community Development Journal, 44(2), 186-208.

- Spanoudis, C. (1982) Trends in tourism planning and Development; Tourism management, 3(4): 314-318

- Timothy, D.J. (1998) Co-operative tourism planning in a developing destination. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 6(1), pp.52-68.

- Timothy, D.J. (1999) Participatory planning. A view of tourism in Indonesia. Annals of Tourism Research. 26(2), pp.371-391.

- UNWTO. (2013). Sustainable Tourism for Development. Available at http://icr.unwto.org/content/guidebook-sustainable-tourism-development

- UNWTO. (World Tourism Organization). 2012. Tourism Highlights, 2012Edition. Available at http://www.unwto.org/pub/index.htm.

- Yamane, T. (1967). Statistics: An Introductory Analysis, 2nd Ed. New York: Harper and Row.