Financial System Development and Economic Growth: Evidence from Nigeria

Ebiringa Oforegbunam Thaddeus*, Duruibe Stanley Chigozie

Department of Management Technology, Federal University of Technology, Owerri, Nigeria

Abstract

This paper analyzed nature of relationship between financial system development and economic growth in Nigeria using vector autoregressive model. The objective to validate the hypothesis, which suggest that growth experienced by the money and capital markets has not translated to long run growth of the economy. The results reveal among others that long run causality does not run from financial system development indicators and economic growth, implying that financial system development seem not to significantly catalyse economic growth trends in Nigeria. However, in specific terms, the effect of financial system development on economic growth has been positively significant only in the short run. The paper concludes that for the financial market to adequately support short and long-term growth of the Nigerian economy, the financial system need further deepening through offering and delivery of innovative financial products and service by market operators, formulation and implementation of sound monetary policies and regulations.

Keywords

Stock Market, Credit Market, Financial Deepening, Monetary Policy, Industrial Productivity

Received: March 17, 2015

Accepted: April 6, 2015

Published online: June 8, 2015

@ 2015 The Authors. Published by American Institute of Science. This Open Access article is under the CC BY-NC license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

1. Introduction

A number of studies have documented evidences proving that financial system development plays a fundamental role in the economic growth of countries. Many countries have experienced successful financial sector reforms which have been followed by improvements in economic growth and the efficiency and development of the financial system, while in some it has resulted in financial crises and disruptions to economic growth. The financial system reforms in Nigeria which took a robust dimension with the introduction of the Structural Adjustment Program in 1986, no doubt, affected the overall level of financial development in the country and the importance of the financial system to economic growth. Financial reforms are initiated to create a sound and efficient financial system that will effectively mobilize financial resources for economic growth and development. It has been contented that the greater the degree of financial development, the wider the availability of financial services that allows for diversification of financing risk. This increases the long run growth trajectory of a country and ultimately improves the welfare and prosperity of citizens to have access to financial services. (Patrick 1966).

Three main channels through which the financial sector may affect economic growth exist. First, developing the financial sector makes room for increased savings. As through economies of scale and expertise, financial intermediaries and markets are able to provide savers with a relatively higher yield and therefore stimulate savings. Secondly, by reducing information and transaction costs financial intermediaries and markets perform the essential economic function of increasing the channelling of funds from surplus lenders to deficit units (Gurley and Shaw, 1967). Thirdly, the financial sector improves the allocation of resources. A recent line of research argues that financial development enhances growth by promoting the efficient allocation of investment through fund pooling; Risk diversification; liquidity management; investment screening and monitoring. A well-functioning financial system improves resources allocation through these mechanisms. Therefore, the above instances lend credence to the fact that policies to develop the financial system would be expected to lead to economic growth.

In spite of many reforms implemented so far, the Nigerian financial sector has not been able to live up to its expectation as the propeller of economic growth and development. Nzotta and Okereke (2009) insist that the financial system has not sustained an effective financial intermediation, especially credit allocation and a high level of monetization of the economy. Equally, the Structural Adjustment Program introduced in 1986, led to the closure of many firms and a rapid decline in manufacturing sector capacity utilization; poverty on the increase; power sector is in comatose; rural finance at its ebb; inequality in the distribution of national income among widened (Adegbite, 2004). These aforementioned phenomenon cast doubt on whether the financial sector reforms implemented has had significant positive effect on economic growth and development. It is against this backdrop that this paper empirically investigates the relationship between financial development and economic growth in Nigeria, with the objective of validating the hypothesis: financial system development in Nigeria has not led to significant growth of the country’s economy.

2. Theoretical and Empirical Literature

Several studies have proven, both empirically and theoretically, that there is a significant relationship between financial sector development and economic growth. A discuss of the financial sector development and economic growth and development normally begins with the path-breaking work of Hicks (1969), Mckinnon (1973), and Shaw (1973).They are all in agreement that the level of financial system development has a crucial role to play in the overall economic growth. Before then the relationship between financial development and economic growth has caught the attention of economist such as Joseph Schumpeter (1911) who argued that the services provided by financial intermediaries such as mobilizing savings, evaluating projects, managing risk, monitoring managers and facilitating transaction are essential for the technological innovation and economic development of a nation; although the channel and even the direction of causality have remained unresolved in both theory and empirical discuss. Goldsmith (1969) shows a close relationship between financial development and economic growth for a few countries. Adegbite (2004), using the ratio of broad money supply (M2) to GDP as a measure of financial sector development and deepening, he found a positive correlation between financial sector growth and real sector growth in Nigeria. However, the study did not establish a causal link between the two. Beneirenga and Smith (1991) had earlier argued that in a well-developed financial system where the security market is also developed, the ability of the financial system to impact liquidity to long term instruments stimulates savers to hold their wealth in productive assets (debenture, stocks, preferential stocks etc) and this contributes to productive investment and growth. Umar (2010) examined the long run relationship between financial development indicators and economic growth in Nigeria using annual time series for the period 1960 – 2005 using the Multivariate Vector Autoregressive (VAR) model through test of exact and over-identifying restriction in co-integration vectors. The empirical result suggest the existence of unidirectional causality from financial development to economic growth when bank credit to the private sector is used as measure of financial development and bidirectional between financial development and economic growth when domestic credit to private sector and bank deposit liabilities are used as indicators of financial development. In a similar study Tokunbo (2000) employed the ordinary least square (OLS) to test the relationship between stock market development and economic growth in Nigeria. The study confirmed the existence of positive relationship between economic growth and measures of stock market development used. Furthermore, Erdal Guryay et al (2007) examined the relationship between financial development and economic growth in Northern Cyprus using the ordinary least square statistical technique and found financial development making a negligible positive effect of on economic growth. However, the result showed evidence of causality from economic growth to the development of financial intermediaries. King and Levine (1993), and Levine and Zervos (1996) examined the nexus between economic growth and financial development by estimating cross country regressions and they found that financial development level is a close predictor of economic growth. They concluded that financial development leads to growth. Adamopoulos (2010) used cross-country data covering the period 1965-2007, found that stock and credit market development had significant positive effect on economic growth for nine out of fifteen (15) European Union (EU) countries sampled.

A lot of empirical tests have shown that financial variables have important impacts on economic growth. However most of the evidence uses bank-based measures of financial development such as ratio of liquid liability of financial intermediaries to GDP and domestic credit to the private sector divided by GDP. Not until recently has the emphasis increasingly shifted to stock market indicators, due to increasing role of financial markets in economies. Atje and Jovanovic (1993), Levine and Zervos (1996, 1998) and Singh (1997) found that stock market development is positively and robustly associated with long run economic growth. In addition, using cross-country data for 47 countries from 1976-1993, Levine and Zervos (1998) find that stock market liquidity is positively and significantly correlated with current and future rates of economic growth, even after controlling for economic and political factors. They also find that measures of both stock market liquidity and banking development significantly, predicts future rates of economic growth. Theory also points out a rich array of channel through which the stock markets (markets size, liquidity, integration with world capital markets and volatility) may be linked to economic growth. Pagano (1993) shows that increased risk-sharing benefits from larger stock market size through market externalities, while Levine (1991) and Bencivenga, et al (1996) show that stock markets may affect economic activity through the creation of liquidity. Similarly Devereux and Smith (1994) and Obstfeld (1994) show that risk diversification through internationally integrated stock markets is another vehicle through which the stock market can affect economic growth.

Besides stock market size, liquidity, and integration with world capital markets, theorists have examined stock return volatility. For examples, De Long et al. (1989) argue that excess volatility in the stock market can hinder investment, and therefore growth. However, some economists believe that finance is a relatively unimportant factor in economic development. Prominent among them is Robinson (1952) who argued that financial development simply follows economic growth. Hence he claims that "where enterprise leads, finance follows". According to his view, economic development creates demand for particular types of financial arrangement and the financial system responds automatically to these demands. More recently Lucas (1988; p6) assert that economist "badly over- stress" the role of financial factors in economic growth, while development economists in most cases frown at the purported role of the financial sectors by not putting it into consideration (Chandavarkar 1992).

3. Research Methodology

Economic growth is proxy by gross domestic product (GDP), while the credit market development is expressed by the domestic bank credits to private sector (DCPBS) as a percentage of GDP is used as a measure of financial depth and banking development. Market capitalization as a percentage of GDP (MKTCAP) is used as a proxy stock market development while the industrial production index (IPI) measures the growth of industrial sector (Katsouli, 2003; Nieuwerburgh et al., 2005; Shan, 2005; Guisan and Neira, 2006; Vazakidis, 2006; Vazakidis and Adamopoulos, 2009b; Vazakidis and Adamopoulos, 2009c; Guisan, 2009). The data used are annual covering the period 1986– 2011 and were obtained from the CBN statistical bulletin, International Finance Statistic, and World Bank databank.

The functional relationship is specified as follows:

GDP= f (MktCap, DCPBS, IPI). (1)

Since all the variables, apart from GDP, are stationary at first difference from the ADF unit root test we conducted (see Table 1), we did the Johansen co-integration test. The essence is to know if the variables are co-integrated. If the variables are co-integrated, it means there is a long term equilibrium relationship among the variables, hence, we run the Vector Error Correction Model (VECM) is given as:

![]() (2)

(2)

The Breusch-Godfrey, Breush-Pagan-Godfery, and Jarque-Bera tests of serial correlation, heteroscedasticity, and normality test respectively were equally conducted to test the adequacy and viability of our VECM model.

4. Results and Discussions

Table 1. Summary of Dickey Fuller Unit Root Test.

| ADF | Critical Values. | ||||

| 1% | 5% | 10% | |||

| GDP | Level | 6.537916 | -3.711457 | -2.981038 | -2.629906 |

| First Diff | - | - | - | - | |

| MKTCAP | Level | -2.342646 | -3.711457 | -2.981038 | -2.629906 |

| First Diff | -6.852729 | -3.724070 | -2.986225 | -2.632604 | |

| DCPBS | Level | -2.798244 | -3.711457 | -2.981038 | -2.629906 |

| First Diff | -4.990245 | -3.724070 | -2.986225 | -2.632604 | |

| IPI | Level | -3.310219 | -3.711457 | -2.981038 | -2.629906 |

| First Diff | -4.581229 | -3.724070 | -2.986225 | -2.632604 | |

Table 2. Summary of Johansen Co-integration test.

| Included observations: 25 after adjustments Trend assumption: Linear deterministic trend Series: GDP DCPBS MKTCAP IND Lags interval (in first differences): 1 to 1 | |||||

| UNRESTRICTED CO-INTEGRATION RANK TEST (TRACE TEST). | |||||

| Hypothesized No. of CE(s) | Eigenvalue | Trace Statistic. | Critical Value(0.05) | Prob. Value** | |

| None* | 0.784122 | 67.49308 | 47.85613 | 0.0003 | |

| At Most 1 | 0.504643 | 29.16698 | 29.79707 | 0.0590 | |

| At Most 2 | 0.361186 | 11.60507 | 15.49471 | 0.1769 | |

| At most 3 | 0.015933 | 0.401532 | 3.841466 | 0.5263 | |

| UNRESTRICTED CO-INTEGRATION RANK TEST (MAX-EIGENVALUE). | |||||

| Hypothesized No. of CE(s) | Eigenvalue | Max-Eigen Statistic. | Critical Value(0.05) | Prob. Value** | |

| None* | 0.784122 | 38.32609 | 27.58434 | 0.0014 | |

| At Most 1 | 0.504643 | 17.56192 | 21.13162 | 0.1471 | |

| At Most 2 | 0.361186 | 11.20354 | 14.26460 | 0.1443 | |

| At most 3 | 0.015933 | 0.401532 | 3.841466 | 0.5263 | |

Trace test indicates 1 cointegrating eqn(s) at the 0.05 level

Max-eigenvalue test indicates 1 cointegrating eqn(s) at the 0.05 level

*denotes rejection of the hypothesis at the 0.05 level.

**MacKinnon-Haug-Michelis (1999) p-values

Table 2 shows the Trace test indicates that there is one co-integrating equation or Error Correction Term which is thereafter confirmed by the Max-eigenvalue test. The null hypothesis of the non-existence of co-integration among the variables is rejected at the 5 percent level for both statistics. The presence of co-integration among the variables implies that there is a long run relationship between GDP, our proxy for economic growth, and the financial development indicators, and this is coherent with the finance-led theories.

Table 3. Summary of VECM

| Dependent Variable: D(GDP) Method: Least Squares Error Correction Method. Sample (adjusted): 1988 2012 | ||||

| Variables | Coefficients | Std-Errors | T-Statistic | Prob. |

| ECM(-1) | 0.104533 | 0.023610 | 4.427516 | 0.0003 |

| D(GDP(-1)) | 0.255116 | 0.164934 | 1.546773 | 0.1384 |

| D(DCPBS(-1)) | 0.007779 | 0.004832 | 1.609899 | 0.1239 |

| D(MKTCAP(-1)) | 0.010064 | 0.004331 | 2.323967 | 0.0314 |

| D(IND(-1)) | -0.000321 | 0.003988 | -0.080444 | 0.9367 |

| C | 0.320039 | 0.066608 | 4.804818 | 0.0001 |

| R-squared | 0.813867 | Mean dependent var | 0.418000 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.764884 | S.D. dependent var | 0.306050 | |

| S.E. of regression | 0.148400 | Akaike info criterion | -0.772251 | |

| Sum squared resid | 0.418427 | Schwarz criterion | -0.479721 | |

| Log likelihood | 15.65313 | Hannan-Quinn criter. | -0.691115 | |

| F-statistic | 16.61549 | Durbin-Watson stat | 2.007401 | |

| Prob(F-statistic) | 0.000002 | |||

![]() = 0.32 + 0.26GDPt -1 + 0.01MktCapt-1 + 0.01DCPBSt-1 – 0.0003IPIt-1 + 0.105ECMt-1 (3)

= 0.32 + 0.26GDPt -1 + 0.01MktCapt-1 + 0.01DCPBSt-1 – 0.0003IPIt-1 + 0.105ECMt-1 (3)

The VECM output in Table 3 and equation above was tested for serial correlation, heteroskedasticity and normality using the Breusch-Godfery serial correlation LM test, Breusch-Pagan-Godfery heteroskedasticity test and Jaque-Bera test of normality respectively. The results of the tests, as presented in Tables 4 and 5, show that our model specification is adequate and viable for econometric analysis. Meanwhile, from the VECM model in table 3, R2 is considerably very high indicating a good model fit. The F-statistic is significant indicating that all the independent variables can jointly influence the dependent variable.

Table 4. Breusch-Godfrey Serial Correlation LM Test:

| F-statistic | 0.012624 | Prob. F(2,17) | 0.9875 |

| Obs*R-squared | 0.037073 | Prob. Chi-Square(2) | 0.9816 |

The observed R2 value of 0.0.037 (3.7%) (see Table 4) suggests the acceptance of the null hypothesis. Thus there is no serial correlation in our model and this is desirable.

Table 5. Heteroskedasticity Test: Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey.

| F-statistic | 0.510208 | Prob. F(8,16) | 0.8316 |

| Obs*R-squared | 0.081329 | Prob. Chi-Square(8) | 0.7488 |

| Scaled explained SS | 2.346819 | Prob. Chi-Square(8) | 0.9685 |

The observed R2 value of 0.0813 (Table 5) suggests the acceptance of the null hypothesis. Thus there is no heteroskedasticity in our model and this is desirable.

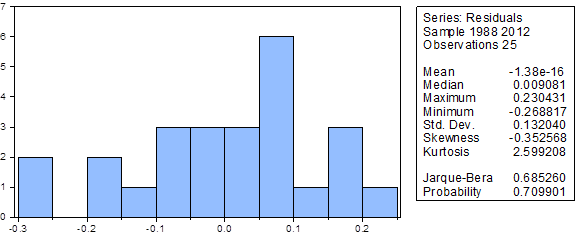

Fig. 1. Jaque-Bera Test of Normality.

The p-value of 0.71 as shown on fig 1, suggests the acceptance of the null hypothesis. Thus our model is normally distributed and this is desirable.

All the explanatory variables apart from Index of Industrial production as shown by the VECM output in table 3, have a positive relationship with GDP. IND is inversely related to GDP. This finding is contrary to our apriority expectation. It also reveals that credit market development do not have a significant influence on economic growth in Nigeria. This finding, no doubt, is predicated on the fact that the high returns on government securities and the various banking sector crises of the late 80s and 90s have been responsible for low level of banking credit to the private and the real sector of the Nigerian economy over the years. Moreover, most of the bank lending in the system goes to blue chip companies and for speculative purposes.

Government rates are attracting banks to invest in government securities thereby shutting out the private sector. It will require a proactive policy by the CBN for the banks to begin serious lending to the real sector because yields on government securities are so attractive to them. Furthermore the problem of huge non-performing loans as a result of investment inefficiency, and a deficient legal system all serve as a limiting factor to the significance of the Nigerian credit market to economic growth.

However stock market development has a positive and significant influence on economic growth in Nigeria indicating that improving the stock market will propel the engine of economic growth in Nigeria. This is consistent with the findings of Tokunbo (2000) and Emeka and Aham (2013). Similarly, Index of Industrial production in Nigeria which measures the output from the manufacturing, gas and electricity sector do not have a significant and positive effect on economic growth in Nigeria. There is no doubt in this finding as it is clear that the Nigerian manufacturing and electricity sector have been operating at a below optimal level during the periods under study. The Structural Adjustment Program introduced in 1986, led to the closure of many firms and a rapid decline in our manufacturing sector. This situation is further exacerbated by the ailing power sector in Nigeria. It is worthy to note that the gains in economic growth during this period under review must have been triggered by factors that were not captured in this model as the independent variables only explains 81% of the total variation in economic growth represented with GDP as depicted by R2. The coefficient of ECM(-1), which is 0.104533 (see table 4) is the speed of adjustment towards long run equilibrium, but it must be significant and the sign must be negative. But if the coefficient is significant but not negative as in this case, it means that there is no long run causality from the three independent variables, meaning that our independent variables have no influence on the dependent variable (GDP) in the long run. In other words, we can conclude that there is no long run causality running from the independent variables to the dependent variable.

5. Conclusions and Recommendation

In the light of the forgoing we are inclined to suggest that in order to consolidate the gains from the various banking reforms in Nigeria, adequate measures have to be put in place for the impact of the consolidation to be felt in the real sector of the economy by means of boosting the ability of banks to provide long-term finance to the private sector. Moreover, there is need to adequately deepen the financial system through financial innovations, sound regulation and supervision, improving its legal system, efficient mobilization of funds and making such funds available for productive investment, and improved services. As stock market development promotes economic growth in the country under study, we therefore suggest the pursuit of policies geared towards rapid development of stock market in Nigeria and the sustenance of the gains so far recorded in the stock market of the country.

The need to revamp the industrial sectors in Nigeria so that they will propel the engine of economic growth is suggestive here. This paper leaves open the possibility of future extensions in investigating the relationship between financial development and economic growth. First, our result show that the set of financial development indicators used as the independent variable in the economic growth function collectively account for 81 percent of the variation in the outcome variable. This implies that 19 percent of the variation is accounted for by variables not considered by our model. Introduction of other predictor variables such as the ratio of M3 to GDP to measure the liquid liabilities in the economy, the ratio of gross domestic saving to GDP, the ratio of trade to GDP, the ratio of financial system asset to GDP, etc may not only reveal a stronger model fit, but may add to variables that are significant for the purpose of predicting the long term relationship between financial development and economic growth. Secondly, it would be interesting to carry out a study which compares the relationship between financial development and economic growth in Nigeria with that of other developing countries such as Kenya, South Africa and Zambia to determine how the results differ amongst countries with similar economic structures.

References

- Patrick, H. (1966). Financial Development and Economic Growth in Underdeveloped countries. Economic Development and Cultural Change. 141 (2):174-189.

- Gurley, J. and Edward S. (1955). Financial Aspect of Economic Development. American Economic Review, pp.515-538.

- Gurley, J. and Edward S. (1960). Money in a Theory of Finance. Washington D.C. Brookings Institution.

- Gurley, J. and Edward S. (1967). Financial Structure and Economic Development. Economic Development and Cultural Change 34(2):333-346.

- Hicks, J.R. (1969). A Theory of Economic History. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- Mc Kinnon, R.I. (1973). Money and Capital in Economic Development. the Brookings Institution Washington D.C.

- Shaw, E.S. (1973). Financial Deepening in Economic Development. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Schumpeters, J. (1911). The Theory of Economic Development. Harvard University Press.

- Adegbite E.O (2004). Financial Institutions and Economic Development in Nigeria. in Adejugbe M.O.A (ed.) Industrialization, Urbanization and Development in Nigeria, 1950-1999. Lagos Concept Publications.

- Goldsmith, R. W. (1969). Financial Structure and Development. New Haven C.T: Yale University Press.

- Tokunbo S. O. (2000). Does Stock Market Promote Economic Growth in Nigeria. Thesis, University of Ibadan, Ibadan.

- Levine R. and Sara Z. (1996). Stock Market Development and Long Run Growth. Vol. 10, No. 2.

- Levine R. and Sara Z. (1998). Stock Markets, Banks and Economic Growth. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, No.1690.

- Atje, R and Boyan J. (1993). Stock Markets and Development. European Economic Review 37(2/3), pp. 632-640.

- Singh, A. (1997). Stock Markets, Financial Liberalization and Economic Development. Economic Journal 107, pp. 771-782.

- Pagano, M. (1993). Financial Markets and Growth: An Overview. European Economic Review 37, pp. 613-622.

- Levine R. (1991). Stock markets, Growth and Tax Policy. Journal of Finance 46(4): 1445-1465.

- Devereux, M.B. and Gregor, W.S (1994). International Risk Sharing and Economic Growth. International Economic Review, 35(4):535-550.

- De-Long, J. B; Shleifer, A; Summers, L. H. and Waldmann, R. J. (1989). The Size and Incidence of the losses from Noise Trading. Journal of Finance, 44(3): 681-696.

- Nzotta, S.M. and Okereke, E. J. (2009). Financial Deepening and Economic Development in Nigeria: An Empirical Investigation. African Journal of Accounting, Economics, Finance, and Banking Research, Vol.5, No.5.

- Adamopoulos, A. (2010). Financial Development and Economic Growth: A Comparative Study between 15 European Union Member States. Research Journal of Finance and Economics (Issue 35), pp. 143-149.

- Erdal, G., Okan V. Ş and Behiye T. (2007). Financial Development and Economic Growth: Evidence from Northern Cyprus: International Research Journal of Finance and Economics ISSN 1450-2887 Issue 8.

- King, R, and Levine, R (1993). Finance and growth: Schumpeter might be right. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(3): 713-37.

- Bencivenga, V. and Smith, B. (1991). Financial intermediation and endogenous growth. Review of Economics and Studies, 58, pp. 195-209.

- Bencivenga, V., Smith, B. and Starr, R., (1996). Equity Markets, Transaction Costs and Capital Accumulation: An Illustration. The World Bank Economic Review, 10(2): 241-265.

- Obstfeld M. (1994). Risk-Taking, Global Diversification, and Growth. The American Economic Review, Vol. 84, No. 5. pp. 1310-1329.

- Lucas, R. (1988). On the Mechanics of Economic Development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22, pp. 3-42.

- Robinson, J. (1952). The Rate of Interest and Other Essays, London: Macmillian.

- Katsouli, E. (2003). Book Review: Money, Finance and Capitalist Development in Philip Arestis and Malcolme Sawyer (ed), Economic Issues.

- Nieuwerburgh, S., Buelens, F. and Cuyvers, L. (2006). Stock Market and Economic Growth in Belgium. Exploration in Economic History 43(1):13-38.

- Guisan, M.C., Neira, I. (2006). Direct and Indirect Effects of Human Capital on World Development, 1960-2004. Applied Econometrics and International Development, 9(1):17-34.

- Guisan, M.C. (2009). Government Effectiveness, Education, Economic Development and Well-Being: Analysis of European Countries In Comparison With the United States and Canada, 2000-2007. Applied Econometrics and International Development, 9(1): 39-55.

- Vazakidis, A. (2006). Testing Simple Versus Dimension Market Models: The Case of Athens Stock Exchange. International Research Journal of Finance and Economics, pp. 26-34.

- Emeka, N. and Aham, K.U. (2013). Financial Sector Development-Economic Growth Nexus: Empirical Evidence from Nigeria. American International Journal of Contemporary Research, Vol. 3 No. 2.

- Umar, B.N. (2010). Financial Development, Economic Growth and Stock Market Volatility: Evidence from Nigeria and South Africa. JUP Journal of Financial Economics; volume VII, Pg 37 – 58.

- Vazakidis, A. and Adamopoulos, A. (2009). Credit Market Development and Economic Growth. American Journal of Economics and Business Administration 1 (1):34-40.

- Vazakidis, A. and A. Adamopoulos, (2009). Stock Market Development and Economic Growth. American Journal of Applied Science, Vol. 6: 1932-1940.