Effect of Iron Fortified Wheat Flour Consumption on the Hemoglobin Status of Adolescent Girls in District Buner

Fazal Dad1, *, Saleem Khan1, Ijaz Habib1, Bakht Ramin Shah1, 2, Muhammad Sohail1

1Department of Human Nutrition, Faculty of Nutrition Sciences, The KPK Agricultural University, Peshawar, Pakistan

2College of Food Science and Technology, Huazhong Agriculture University, Wuhan, China

Abstract

Food fortification has been defined as the addition of one or more essential nutrients to a food whether or not it is normally contained in the food. Iron acts as an integral part of hemoglobin and is required for the transport of oxygen and carbon dioxide in blood. Cereal foods can be successfully fortified with iron. Among the cereals, wheat has additional advantage to be used as vehicle. The bioavailability of iron added to wheat is several times greater than other staples such as maize and rice. Ferrous sulphate has excellent bioavailability. It is the fortificant of choice when used in wheat flour and is the best iron source because of its high bioavailability and low cost.In this study the effect of ferrous sulphate fortified wheat flour on the hemoglobin status of adolescent girls was examined in district Buner.A total of 200 adolescent girls were randomly selected and divided into two groups, study and control each group having 100 girls. The subjects of the study group were fed with ferrous sulfate fortified wheat flour while the control group were fed with non-fortified wheat flour as a placebo. The hemoglobin level of both groups was determined 4 times, prior to intervention, after 1st, 2nd and 3rd month of consuming ferrous sulfate fortified wheat flour with the help of Hemo Cue. The mean (± S.D) Hb values (g/dl) of control and study groups prior to intervention, after 1st, 2nd and 3rd month were (11.878 ± 0.46, 11.754 ± 0.61), (11.91 ± 0.50, 11.837 ± 0.60), (11.88 ± 0.53, 11.93 ± 0.65), (11.87 ± 0.66, 12.107 ± 0.63) respectively. The results showed no significant difference between study and control groups by comparing baseline data with the 1st month while showed significant difference by comparing baseline data with 2nd and 3rd month of intervention. The study suggests that the hemoglobin status of adolescent girls was significantly improved by consuming wheat flour fortified with ferrous sulphate.

Keywords

Iron Fortification, Ferrous Sulphate, Hemoglobin Level, Wheat Flour

Received:September 29, 2015

Accepted: November 3, 2015

Published online: January 21, 2017

@ 2015 The Authors. Published by American Institute of Science. This Open Access article is under the CC BY-NC license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

1. Introduction

Anaemia is a condition in which the number of red blood cells is insufficient to meet the body’s physiologic needs. Specific physiologic needs vary with a person’s age, gender, residential elevation above sea level, smoking behaviour and different stages of pregnancy. The prevalence of anemia is an important health indicator and when it is used with other measurements of iron status the hemoglobin concentration can provide information about the severity of iron deficiency [1].

Anemia is one of the most commonly recognized disorders. Its prevalence in women and preschool children is high therefore, it needs more attention. Evidence from studies showed that adolescents are at an increased risk of developing anemia due to increasing iron demand during puberty, menstrual losses, limited dietary iron intake and faulty dietary habits [2, 3].

Iron deficiency is most common among groups of low socioeconomic status. The cut off points for mild, moderate and severe anemia in women are 120 g/l, 110-119 g/l and 80-109 g/l respectively [4].

Nutritional iron deficiency is a leading public health concern both in industrialized and developing countries. It affects significant portion of population in the entire developing world including Pakistan. Maximum of our population particularly women and children are more prone to iron deficiency. In 2001 the prevalence of anemia in children was 49.7% and 45% in pregnant women [5] but in 2011 the prevalence of anemia reported in children is 62.5% and 52.1% in women [6].

Recent statistics shows a prevalence of around 45% of iron deficiency anemia in Pakistan realizing failure of public health measures to control it [7]. It has been found that overall more than one fifth of women in Pakistan suffer from anemia [8].

The daily elemental iron requirement for adolescent girls and premenopausal women is approximately 20 mg elemental iron. However, this amount often is not attained because absorption from dietary sources is limited by the absorptive capacity of the intestine. Iron deficiency occurs readily owing to regular iron losses, increased requirements, or decreased intake. In premenopausal women, cumulative menstrual blood loss is a common cause. Vitamin C deficiency can contribute to IDA by producing capillary fragility, hemolysis, and bleeding [9].

Dietary supplements and food fortification have permitted humans to consume micronutrients in sufficient amounts that are not naturally present in foods. It has been claimed that millions of lives are saved each year, and the quality of life of many more is improved by dietary supplements and food fortification. Bread made from refined wheat flour is consumed extensively throughout the world, especially by populations in developing countries. Several countries have passed legislation for the addition of iron and vitamins to wheat flour as a strategy to decrease the high prevalence of iron deficiency [10].

Many studies have shown that iron is well absorbed from bread fortified with iron in the form of soluble salts [11]. However at high levels these salts produce organoleptic changes in the flour, especially when stored for long periods of time. Flours fortified with elemental iron do not undergo the same organoleptic changes because the iron compound is inert; nevertheless, it is absorbed in lower percentages [12].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection and Classification of the Subjects

The current study was conducted in district Buner in adolescent girls [13]. A total of 200 adolescent girls were selected randomly from different union councils of district Buner. Leady Health Workers of national program were involved in enrolment and follow ups of the subject. Inclusion criteria for the study subjects were all adolescent girls who are free of chronic infectious diseases and not taking any medication or iron supplementation. The selected subjects were randomly divided into 2 groups, study and control, each group having 100 subjects. The hemoglobin level of both groups was determined 4 times, prior to intervention, after 1st, 2nd and 3rd month of intervention. The subject of the study group was fed with iron fortified wheat flour while the control group was fed with non-fortified wheat flour as a placebo. The hemoglobin level of both groups was compared to see the effect of iron fortified wheat flour by the help of Hemo Cue [14]. Those who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were asked to sign the consent form for participation in the study. The subjects were interviewed for dietary intake, demographic information and also their BMI was calculated by taking their weight and height according to standard procedures.

2.2. Anthropometry

Weight and height of all individuals was determined by following the recommended procedure of WHO [15]. Before taking weight measurements, the adolescent girls were asked to remove heavy clothing, shoes, purse and other unnecessary things. The weight was noted up to the nearest 0.01kg. Similarly before height measurements, the adolescent girls was asked to remove shoes and heavy garments and to stand in the centre of the platform of the scale, looking straight with his head, back, buttocks, calves and heels touching the rod. The head piece was levelled and height was recorded up to the nearest 0.1cm. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated prior to the experiment with the help of formula, Weight (kg) / Height (m2).

2.3. Dietary and Demographic Information

Data regarding dietary and demographic information like age, education level, occupation, medical history, family size and source of income was collected by interviewing. For dietary assessment 24 hour dietary recall questionnaire was used to see the nutrients intake of the adolescent girls. Dietary assessment was recorded 4 times from each study group on each month to know about the pattern of dietary intake of iron. The 1st was recorded before feeding the fortified and non-fortified wheat flour, second, third and fourth was collected after first, second, and third months of feedings.

2.4. Composite Flour Preparation and Feeding

For composite flour preparation, the flour was collected from one flour shop of the same flour mill, brand and with 75% extraction rate to maintain the same level of phytic acid concentration naturally found in wheat flour. The extraction rate of flour is critical for selecting the type of iron that can be used for fortification. Whole wheat grains are good sources of some of the B-complex vitamins as well as iron and other minerals, which are concentrated in bran. The extent, to which the bran is separated or extracted from the endosperm, or the weight of the flour relative to the original weight of the wheat grain, is known as the extraction rate. Ferrous sulfate is recommended for fortification of wheat flour with 75% extraction rate [16].

The required fortification level of ferrous sulfate for countries consuming wheat flour greater than 300 g/day is 20 ppm [17]. Levels of ferrous sulfate higher than 40 ppm or storage for more than 3 months under high temperatures and humidity have been found to cause rancidity and taste deterioration [18].

One kg of the composite wheat flour based on 143g small bags was given to each individual of the study group for 7 days. Similarly one kg of non-fortified wheat flour based on 143 g small bags was provided to each individual of control group as a placebo. The both groups were instructed to consume one bag per day through preparing bread without sharing to other family members and was provided on weekly basis to both groups for 3 months to see the effect of iron fortified wheat flour consumption on the hemoglobin status of the adolescent girls.

2.5. Determination of Heamoglobin

The Heamoglobin level of both groups was determined by using Hemo Cue. Total of 4 readings of Heamoglobin was taken from each group. First reading was taken before the feeding of the fortified and none fortified wheat flour, second, third and fourth readings was taken after first, second and third months of feeding the fortified and non-fortified wheat flour.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The collected data was entered into computer for statistical analysis using MS Excel and Statistix 8.1 package. Completely randomized design was used to see the variation in mean values between study and control groups at 5% level of significance.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. General Characteristics of the Subjects

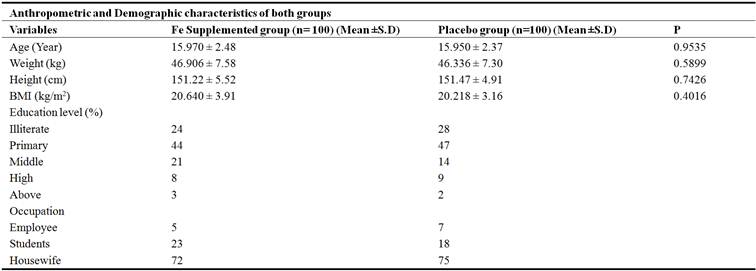

Table-1 describes the general characteristics of the subjects. The mean ages of case and control groups were 15.970 ± 2.48 and 15.950 ± 2.37 years while the mean weights of these groups were 46.906 ± 7.58 and 46.336 ± 7.30 kg respectively. The mean heights of these groups were 151.22 ± 5.52 and 151.47 ± 4.91 cm while the mean BMI of these groups were 20.640 ± 3.91 and 20.218 ± 3.16 kg/m2. Data on BMI showed that all the individuals were neither obese nor underweight as BMI range 20-25 is considered normal [19]. The P-value given in the table indicates that there were no significant differences in the mean values for age, weight, height and BMI among both groups respectively.

Table 1. Anthropometric and Demographic characteristics of the subjects enrolled for the study.

3.2. Nutrient Intake of the Subjects

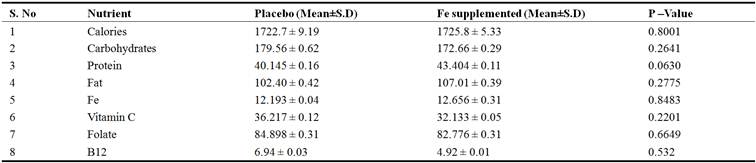

Table 2. Show energy, carbohydrates, protein, fats, iron, vitamin C, B12 and Folate intakes of both groups. The mean energy intake of placebo and study groups were 1722.7 ± 9.19 and 1725.8 ± 5.33 (kcal) respectively. The mean carbohydrate intake of these groups was 179.56 ± 0.62 and 172.66 ± 0.29 (g) respectively. The mean protein intake of these groups was 40.145 ± 0.16 and 43.404 ± 0.11 (g) respectively. The mean fat intake of these groups was 102.40 ± 0.42 and 107.01 ± 0.39 (g) respectively. The mean iron intake of these groups was 12.193 ± 0.04 and 12.656 ± 0.31 (mg) respectively. The mean vitamin C intake of these groups was 36.217 ± 0.12 and 32.133 ± 0.05 (mg) respectively. The mean folate intake of these groups was 84.898 ± 0.31 and 82.776 ± 0.31 (mcq) respectively. The mean B12 intake of these groups was 6.94 ± 0.03 and 4.92 ± 0.01 (mcq) respectively. There was no significant difference in the nutrient intake of the subjects participated in the study at 5% level of significance as determined by analysis of variance during the time frame of the study.

Table 2. Nutrients intake of studied groups.

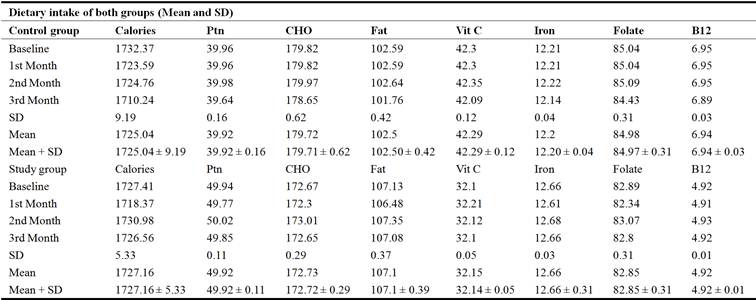

3.3. Dietary Pattern and Food Consumption During the Trail

Table 3. Shows the mean nutrients intakes of control and study group. The mean nutrients intake of control group such as energy was 1725.04 ± 9.19 (kcal), protein was 39.92 ± 0.16 (g), carbohydrate was 179.71 ± 0.62 (g), fats was 102.50 ± 0.42, (g), vitamin C was 42.29 ± 0.12 (mg), iron was 12.20 ± 0.04 (mg), folate was 84.97 ± 0.31 (mcq) and B12 was 6.94 ± 0.03 (mcq). The mean nutrients intake of study group such as energy was 1727.16 ± 5.33 (kcal), Protein was 49.92 ± 0.11 (g), carbohydrate was 172.72 ± 0.29 (g), fats was 107.1 ± 0.39 (g), Vitamin C was 32.14 ± 0.05 (mg), iron was 12.66 ± 0.31 (mg), folate was 82.85 ± 0.31 (mcq) and B12 was 4.92 ± 0.01 (mcq).

Table 3. Dietary intake of both groups.

3.4. Hemoglobin Status of Both Groups

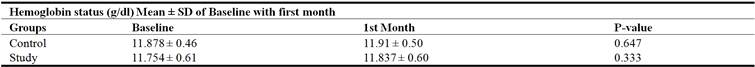

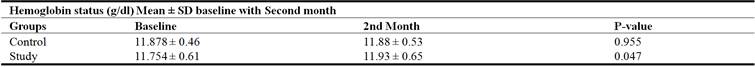

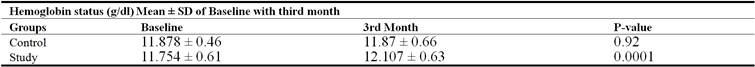

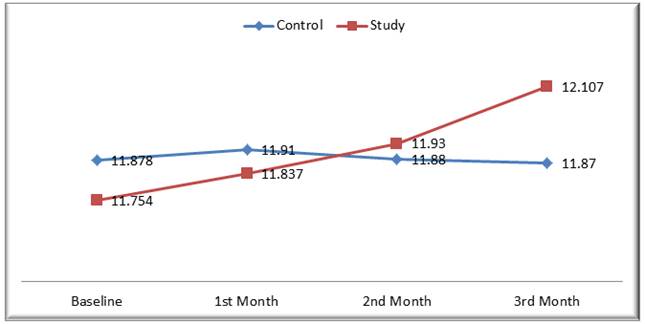

Tables 4, 5, and 6 show hemoglobin status of the subjects of both control and study groups during three months duration in comparison to baseline values. Table 4 shows mean values of hemoglobin at 0 month (baseline) which was 11.878 ± 0.46 and 11.754 ± 0.61 and after one month of the trail that was 11.91 ± 0.50 and 11.837 ± 0.60 for both control and study groups. Table 5 shows mean values of hemoglobin after second month which was 11.88 ± 0.53 and 11.93 ± 0.65 for both control and study groups. Table 5 shows mean values of hemoglobin after third month after the trail that was 11.87 ± 0.66 and 12.107 ± 0.63 of control and study groups. Hb status of the FeSO4 group showed significant effects at second and third month than that of the baseline and control groups [20]. There were significant differences in the hemoglobin values of the study groups at second and third month of the trial while no significance differences were observed during the trial in the hemoglobin valves of control groups.

Table 4. Hemoglobin status baseline with first month.

Table 5. Hemoglobin status baseline with second month.

Table 6. Hemoglobin status baseline with third month.

Figure 1. Month wise Hb comparison of study and control groups.

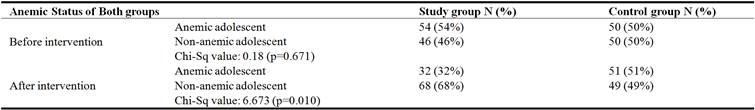

Table 7. Anemic status of both groups before and after intervention.

Table 7 shows the prevalence of anemia in adolescent girls before and after intervention in both cases control and study. Anemia was equally distributed among the both groups before intervention (p >0.05), however a visible reduction in anemia prevalence was evident in intervention group comparing to control (p <0.05). These findings reflect a positive and strong impact of intervention on iron status of adolescent girls.

4. Conclusion

The current study was conducted in district Buner to see the effect of iron fortified wheat flour consumption on the hemoglobin status of adolescent girls. Two hundred adolescent girls were selected randomly. The selected subjects were randomly divided into 2 groups, study and control, each group having 100 subjects. Dietary assessment was recorded 4 times from each study group on each month to know the pattern of dietary intake of iron. One kg of the composite wheat flour of 20 ppm ferrous sulfate / kg of wheat flour based on 143g small bags was given to each individual of the study group for 7 days. Similarly one kg of non-fortified wheat flour based on 143 g small bags was provided to each individual of control group as a placebo. The both groups were instructed to consume one bag per day through preparing bread without sharing to other family members and were provided on weekly basis to both groups for 3 months. The dietary intake and hemoglobin level of both groups were determined four times, prior to intervention, after 1st, 2nd and 3rd month of intervention. The mean nutrients intake of control group such as energy was 1725.04 ± 9.19 (kcal), protein was 39.92 ± 0.16 (g), carbohydrate was 179.71 ± 0.62 (g), fats was 102.50 ± 0.42, (g), vitamin C was 42.29 ± 0.12 (mg), iron was 12.20 ± 0.04 (mg), folate was 84.97 ± 0.31 (mcq) and B12 was 6.94 ± 0.03 (mcq). The mean nutrients intake of study group such as energy was 1727.16 ± 5.33 (kcal), Protein was 49.92 ± 0.11 (g), carbohydrate was 172.72 ± 0.29 (g), fats was 107.1 ± 0.39 (g), Vitamin C was 32.14 ± 0.05 (mg), iron was 12.66 ± 0.31 (mg), folate was 82.85 ± 0.31 (mcq) and B12 was 4.92 ± 0.01 (mcq). The mean values of hemoglobin level at baseline was 11.878 ± 0.46 and 11.754 ± 0.61 and after one month of the trail was 11.91 ± 0.50 and 11.837 ± 0.60 for both control and study groups. The mean values of hemoglobin level after second month was 11.88 ± 0.53 and 11.93 ± 0.65 for both control and study groups recorded. and after third month of trail was 11.87 ± 0.66 and 12.107 ± 0.63 of control and study groups.

These results have shown that the Hb level of control group did not change significantly within the 3 months trails of the intervention while on the other hand the fortified flour has significant and positive effect on the Hb level of the study group.

References

- Assessing the iron status of populations: report of a joint World Health Organization/ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention technical consultation on the assessment of iron status at the population level, 2007, 2nd edi WHO, Geneva.

- Armstrong, P L Iron deficiency in adolescents, B. M J. 1989, 298: 499.

- Sjolin S Anemia in adolescence Nutri Rev.1981; (39): 96-98.

- Iron deficiency anaemia: assessment, prevention and control, 2001, World Health Organization, Geneva. 4.

- National Nutrition Survey Pakistan, Aga Khan Uni Pak Med Res Council (PMRC) Nutri Wing, Cabinet Divi, 2001, Govt of Pak.

- National Nutrition Survey Pakistan, Aga Khan Uni Pak Med Res Council, (PMRC) Nutri Wing, Cabinet Divi, 2011, Govt of Pak.

- Govt of Pak Finance Division, Economic Survey 2005-06 Islam.

- Mother and Child Health in Pakistan Population stabilization a priority for development Islamabad: Ministry of Population Welfare, 2005, Govt of Pak.

- Haddad E H., S. L Berk, D. J Kettering Dietary intake and biochemical, hematologic, and immune status of vegans compared with non-vegetarians Am.J Clin Nutr 1999, 70: 586S-593S.

- Hertrampf E Iron fortification in the Americas Nutr Rev 2002, 60 (2): 22–5.

- Cook, J. D., V Minnich, C V Moore, A Rasmussen, W. B Bradley, C. A Finch Absorption of fortification iron in bread Am J Clin Nutr. 1973, (26): 861–72.

- Walter T., F Pizarro, A. S Abrams, E Boy Bioavailability of elemental iron powder in white wheat bread Eur J Clin Nutr 2004, 58 (3): 555-8.

- Shatha S, A l Sharbatti, Nada J, A. l. Ward, J Dhia, A l Timimi Anemia among adolescents Saudi Med J 2003, Vol 24 (2): 189-194.

- Nkrumah B., N B Samuel, S Nimako, D Denise, I Ali, M Juergen S A Yaw Hemoglobin estimation by the Hemo Cueportable hemoglobin photometer in a resource poor setting B. M. C Clin Path 2011, 11: (5) 1186-1472.

- Expert committee on physical status, the use and interpretation of anthropometry WHO technical report 1983, series no 854, World Health Organization, Geneva.

- Ritu, N., and Penelope, N Manual for wheat flour fortification with Iron 2000, Part 2 technical and operational guidelines.

- Hurrell R., P Ranum, S depee, R Biebinger, L Hulthen, Q Johnson, S Lynch Revised recommendations for the iron fortication of wheat flour and evaluation of the expected impact of current national wheat flour fortification programs Food and Nutr Bult 2009.

- Anjum F. M., Z Adnan, A Ali, H Shahzad Use of iron as fortificant in whole wheat flour and in leavened flat breads in developing countries E. J. E. A. F 2006, 5: (3) 1366-1370.

- Corine, H., R Marilyn, L Wanda, and E Ann Normal and therapeutic nutrition 1986, 17th edition Collier Macmillan Publishers London.

- Sun J., J Huang, W Li, L Wang, A Wang, J Huo, J Chen and C Chen Effects of wheat flour fortified with different iron fortificants on iron status and anemia prevalence in iron deficient anemic students in Northern China Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2007, 16 (1): 116-121.