Basic Rights on the Wane, Human Rights on Brown Study: A Case Study on Thrown Away Children in Bangladesh

M. Kamruzzaman1, 3, 4, *, M. A. Hakim2

1School of Victimology and Restorative Justice, Institute of Social Welfare and Research, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh

2School of Food Technology and Nutritional Science, Mawlana Bhashani Science and Technology University, Tangail, Bangladesh

3School of Criminology and Police Science, Mawlana Bhashani Science and Technology University, Tangail, Bangladesh

4School of Law, National University, Gazipur, Bangladesh

Abstract

The aim of this study was to shed light on the predicaments of the thrown away children in their ongoing social life and also their situational analysis of basic and human rights in Bangladesh. The primary aim of this study is coming to fight the response of communities, the UNICEF, the ILO and many social and human rights organizations about the thrown away children in Bangladesh and the second aimis drawing successful strategies to make exploitation free life on the basis of the existing laws to eradicate the child abuse arranging safe childhood.

Keywords

Thrown Away Children, Basic Rights, UNICEF, Human Rights, Case Study, Bangladesh

Received:May 20, 2016

Accepted: July 11, 2016

Published online: August 5, 2016

@ 2016 The Authors. Published by American Institute of Science. This Open Access article is under the CC BY license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

1. Introduction

The greatest English poet William Butler Yeats, a Nobellaureate in Literature once says,

"Come away, O human child!

To the waters and the wild

With a fairy, hand in hand,

For the world's more full of weeping

Than you can understand." [1]

Children ‘lost, stolen and disappearing’and 'robbed’ of their childhood below at their 18 years ages living, working, playing and sleeping on the street or any other unhygienic conditions are deprived of basic rights are the thrown away children [2-8]. Like all other children although they have the basic rights to develop, survive and thrive, they encounter innumerable problems and their predicaments are shocking and surprisingly most of the people in Bangladesh even do not "bat an eye at street children sleeping in the mid-afternoon sun" [9]. So now it is time to let their plight be known to all to let the conscience of humanity revolt [10-13]. According to Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, among a total child population (5-17 years old) of 42.39 million the total number of working children in urban areas of Bangladesh is estimated 1.5 million. Many of these children living, working, playing and sleeping on the streets and are deprived of their human rights [14]. Three are numerous children living on street in the big cities and towns particularly in Dhaka city. They live an inhuman life and a significant portion of them are involved in begging [15-17]. These children who are in lacking the proper requirements of life and they are tagged as ‘severely deprived’ children. These severe deprivations can be found with their not having the adequate services in the provision of shelter, food, sanitation, water, information, nutrition, education, and health etc [18-20]. Despite constitutional recognition of the right to shelter for all citizens, 41% of all children are deprived of adequate shelter [21-23]. These children are in vogue as a part of thrown away (forced to leave home) children in more developed nations more likely to come from single-parent homes or due to the consequence of polygamy in different societies across the world [24,25]. These fellow children are often subject to abuse, neglect, exploitation, or extreme cases, murder by clean-up squad hired by businessmen, criminal gang and very often the police to retain great business benefit [26-28].

Bangladesh has a high incidence of thrown way children because half of its population living below poverty line. For this reason children have to work for their families survive. Poverty and child labour are associated with each other and these have significant impacts on childhood malnutrition and incompetent labor force of a nation [29,30]. Besides, there are many conspicuous causes behind the harsh curtain of their life, such as over population, family disintegration, unemployment, illiteracy, unplanned urbanization, landlessness, natural disasters, oppression of step father or mother’s non-social behaviours [31-33] etc., which are indeed quite pathetic and matters of investigation and these problems are to be tackled in the best possible ways for the overall betterment of these ill-fated children [34,35].

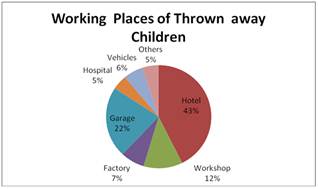

Figure 1. Working places of thrown away children in Bangladesh [31].

In 2015, 42.6% thrown away children worked in hotel, 22% in garage, 12% in workshop 7% in factories and 6% in vehicles. A study done by Kamruzzaman and Hakim (2015) summarizes that among the homeless children 32.9% work in restaurant, 18.8% in industry, 11.8% in transport and 18.8% in Industries Dhaka city [31]. Summon (2007) summarizes that there are five factors that can lead to child labor in Bangladesh. He also said that illiterate and poor are interring related [36]. The thrown away children are poor because they are illiterate and illiterate because they are poor [37] Some social factor that can be include dynamics of parents and children as a family unit and socio-economic inequality that can be lead to child labour in Bangladesh [38-41]. The ILO also estimated that there are 30% of children in Bangladesh are economically active [42].

2. Situational Analysis of Thrown Away Children in Bangladesh

Bangladesh is an agricultural and most of the people are poor and the average family size is 5-7 persons. Most of the families’ father works as a rickshawpuller or day laborer and the mother as a domestic help. Poverty leads to quarrels, tension and can ultimately resultin cruel treatment of children which result in thrown away situation [43,44]. The huge percentage of homeless children is found to be the malnutrition gainers by dint of lacked access to safe drinking water, inadequate nutritious foods, lack of hygiene practices and shelter [45-47]. These thrown away children are the different diseases sufferers on the basis of seasonal variation and some are chronic health disorders sufferers according to their dwelling topographic variation. About 73% of street children in Dhaka city suffer from chronic malnutrition while mortality and morbidity status among street dwellers has reached an alarming level for lack of basic health and nutritional care services [48-50]. In line with this, the homeless population in Dhaka, of which a significant number is the child beggars; is known to face extortion, erratic unemployment, exposure to violence, sexual harassment, and to engage in high-risk behaviors. Sometimes they are engagedin various kinds of criminal activities by touch of criminal gang and peers [27,31]. These thrown away children are in deprivation to their rights to rights to survival, education and safe childhood [28].

3. Perspective of the UNICEF

The UNICEF has already started works with the government of Bangladesh to reduce child labor and establish learning in urban area because in urban area a lot of thrown away children working in garments industry and textile mills. They through aproject called Basic Education for Hard to Reach Urban Working Children (BEHTRUWC). Their learning centers provide basic education in Bangle, English, Social Science and Mathematics. They also learn life-skills education, interpersonal relationships, critical thinking and decision making that can be help children future life. The basic education course duration is 40 months and there are five learning cycles of eight months. Students work and study in small groups. These groups are making according their skill level and sometimes random selection to encourage peer to peer learning [51]. This program contributes to national efforts to eliminate the worst forms of child labor in Bangladesh. In 2010 UNICEF also developed National Children Policy and its specific objective is to protect children from child labor. UNICEF has been advocating for the creation of a children code in order to harmonize domestic legislation with the convention on the right of the child including article 32 on child labour [52]. They also work with Ministry of Social Welfare and other Ministry and NGOs to undertake the mapping and assessment of Bangladesh child protection system.

4. Perspective of the ILO

In 1999 Bangladesh has ratified the ILO Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention (No. 182) but in 1973 has not ratified the Minimum Age Convention (No. 138). They say that corruption and weak institutional capacity is the main problem in the monitoring process of the government in Bangladesh. The monitoring system addresses only the formal sectors, where as child labour is in the informal economy. Bangladesh government has not taken action toreduce commercial sex with children. ILO conventionno. 182 requires the government to take effective and time bound measures to

a) Prevent the engagement of children in the worst forms of child labour

b) Provide the necessary and appropriate direct assistance for the removal of children from the worst forms of child labour and for their rehabilitation and social integration

c) Ensure access to free basic education and, wherever possible and appropriate, vocational training, for all children removed from the worst forms of child labour.

d) Identify and reach out to children at special risk

e) Take account of the special situation of girls.

In 2001 after ratifying the convention Bangladesh government takes a project to combat the worst forms of child labour in urban areas. At the same time ILO and Royal Netherlands Embassy help a pilot project to develop a time bounded program (TBM) to reduce the worst forms of child labour [53].

5. Perspective of the ASK

The ASK (Ain o Salish Kendra), a national legal aid and human rights organization, provides legal and social support to the disempowered, particularly women, working children and workers. Its goal is to create a society based on equality, social and gender justice and rule of law. It seeks to create an environment for accountability and transparency of governance institutions. It is working to establish human rights especially the child rights in Bangladesh. To fulfill their objectives they arrange seminars, round-table dialogue, monthly publications of human rights report across the country to aware the general people and the policy makers.

6. Perspective of Aporajeo Bangla

This Non-government organization Aporajeo Bangla by name works mainly to protect child rights. From the very beginning they are taking various programmes for the development of thrown away children of the capital city of Bangladesh and they are in need of collaboration of government and communities to solve the basic problem of these children.

7. Perspective of the BELA

The BELA (Bangladesh Environment Lawyers Association) emphasizes on the sustainable development with the protection of environment. In the very present time they raise voice to ensure eco-health for the future generation mostly the rootless children.

8. Application of Human Rights Framework to Curb the Sorry Tales of theThrown Away Children in Bangladesh

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. In 1948, the UN General Assembly passed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which referred in article 25 to childhood as entitled to "special care and assistance" [54-56]. Bangladesh is obliged under both national and international law to protect and promote the rights and interests of children. According to the Article 17 and 19 of the constitution of Bangladesh, the state should take proper measures of free and compulsory education for the children along with equal economic development throughout the country and to fulfilling this condition; the government of Bangladesh under the Ministry of Social Welfare builds up five vagrancy centers. But most of the beggars do not want to spend their time into the vagrancy centers because of various problems along with insufficient food facility, treatment opportunity, rehabilitation insecurity, recreational lacking and so on. In 1990 Bangladesh government passed the primary education Act and in 1993 it established the compulsory primary education system for children age 6 years and above. In 1991 to 1996 the government of Bangladesh adopted the National Children Policy (NCP) and formulated the national plane of action for children [57]. The constitution of Bangladesh and children’s Act 1974 guarantees basic and fundamental human rights and ensures affirmative action for children. The rights are the guiding principles for formulating policies and laws to protect restricting development and hazardous work that can help children to develop in free way. As a result Bangladesh government has taken initially a number of policies and plans to promote equitable inclusive and high quality education to reduce child labor. Bangladesh is a signatory to and has ratified most of the major international convention related to children except for the ILO (International Labour Organization) Minimum Age Convention (No. 138) [58]. Bangladesh has signed and ratified the convention of the Right of the Child (1989) which indicates to protect and promote the rights and interests of the child, such as the right to a compulsory and free education (Article 28 & 29) the right to be protect from exploitative work or performing any work that may be considered hazardous, interferes with the child’s education or is harmful to the Child’s development (Article 32) and right to an adequate standard of living (Article 27). Bangladesh is also the first South Asian country to ratify the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention (No. 182) in March 2001 which imposes an obligation upon to "take immediate and effective measures to secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labour as a matter of urgency" (Article 1). Such as all forms of slavery or practices similar to slavery child prostitution [59], child pornography, using children for illicit activities and work which would harm the physical, social and moral development of children (Article 3) [60,61]. The Government of Bangladesh also ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) and its Optional Protocol as well. Article 7 of UN CRPD ensures the rights of Children with disabilities [62].

9. Discussion

There are many causes like poverty, culture and tradition, barriers to education, market demand, the effect of income shocks on householder and lack of legislation or poor enforcement of existing legislation that can led unsafe childhood in developing country like Bangladesh. Thrown away children has no minimum standard of living so they are forced to go earn livelihood through child labour, that can destroys children creativity and innocence because at that time they need to learn something. It can also damage children physical and mental health and involves children bad activities like drugs, robbery etc. Child labour can also reduce to get good job opportunity because in this life time they need to have a good education. It can also decrease the efficiency of the work force because more uneducated workforce [63-65]. In developing countries like Bangladesh having most of the people are poor and uneducated they are live from hand to mouth and so they have considered the child labor as solution to poverty. A survey states that there are 70% of child labour in Bangladesh is members of landless and floating families to reduce poverty. It is seemed that child labour is very harmful of children in Bangladesh that can lead no right way to growand develop in free way. It can also damage children physical and mental health. We know that children of today become the adults of the future and need invest to protect them. It is also believe that poverty is a great problem in our country that can lead increase child labor but I don’t support this responses that if father is a farmer then his children do work in the field to help them we can change this tradition. Bangladesh is a small country but population size is increasing day by day so population is the main problem in Bangladesh for this reason most of the people are poor and they cannot properly take care of their children. So at first we have to control our population density and ensuring education for all children. Family planning can reduce our population size [25]. We have to build awareness of the parents who are sending their children into factories and textile mills for earning money. It also a matter of great think that some time they are victims by natural disaster and send their children different kinds of works [66,67]. In ruralareas so many child labor here so they have to take another project for rural children to reduce rural child labour and give same opportunity like urban children. They have also taken another project like National Children Policy it can obviously reduce child labour as a social belief. The UNICEF also helps to improve birth registration and at last they are able to give birth certificates everyone in Bangladesh, I believe that this will also reduce child labour [35,62]. The ILO and Netherlands Embassy also help the TBM (time-bounded program) to reduce the worst forms of child labour because it is includes awareness-raising and advocacy, policy andlegal reform, urban informal economy, rural informal economy, basic education, technical education, poverty reduction and unconditional worst forms of homeless children. We know that child labor is a great problem in Bangladesh [68-70].

At first Bangladesh government should immediately take action on corruption because if government has corruption then anyone can not apply their policy. The UNICEF, the ILO can also communicate with local NGOs to apply their policies. They also can take another project food for educating the thrown away children at different sites of the country. For example if the parents send their children for education then they will get food. So most of the parents who are poor they will send their children for education.

10. Conclusion

Bangladesh is one of the poorest countries in South Asia. Most of the families are poor who cannot access their rights at all and they are to face different inhuman conditions to retain their family and social bonding. The situation of thrown away children is in beggar description. So, to make a safe childhood basic and human rights must be ensured for them. We can make employers and families aware and sensitize regarding child rights. We can also make partnership, collaboration and co-operation among stakeholders and their commitment also we can knowledge sharing, mobilizing technical and financial support and strengthening capacity to reduce violence against children and occurrences of exploitation. We have to increase public spending on safe shelter, food, education, expand access and quality of technical and vocational education.

References

- Good reads: Quotes about Children. Available at http://www.goodreads.com/ quotes/tag/children.

- Hakim, M. A. and Rahman, A. (2016). Health and Nutritional Condition of Street Children of Dhaka City: An Empirical Study in Bangladesh. Science Journal of Public Health, 4 (1-1): 6-9.

- S. Stephens. Children and the Politics of Culture in Late Capitalism, Children and the Politics of Culture, S. Stephens, eds. Princeton University Press, pp. 8-9, 1995.

- Hakim MA. Nutritional Status and Hygiene Practices of Primary School Goers in Gateway to the North Bengal. International Journal of Public Health Research, 2015; 3 (5): 271-275.

- UNICEF. Street Children, 2007. Available at http:/www.unicef.org.

- Rahman, A. (2016). Significant Risk Factors for Childhood Malnutrition: Evidence from an Asian Developing Country. Science Journal of Public Health, 4 (1-1): 16-27.

- ARISE, Baseline Survey of Street Children in Six Divisional Cities of Bangladesh, Edited by A. R. f. I. S. C. Environment. Dhaka: Department of Social Services, Ministry of Social Welfare, Government of Bangladesh, 2001.

- T. Hecht, At Home in the street: Street Children of Northeast Brazil. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 8-9, 1998.

- K. Timmerman, Where am I Wearing? A Global Tour to the Countries, Factories, and People that Make Our Clothes. Hoboken, N.J.: Willey. p. 26, 2012.

- S. Agneli, Street Children: A Growing Urban Tragedy: A Report for the Independent Commission on International Humanitarian Issues. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, prologue, 1986.

- Hakim, M. A. and Talukder, M. J. (2016). An Assessment of Health Status of Street Children in Tangail, Bangladesh. Science Journal of Public Health, 4 (1-1): 1-5.

- A. A. Aderinto. Social Correlates and Coping Measures of Street Children: A Comparative Study of Street and Non-Street Children in South-Western Nigeria, Child Abuse and Neglect, vol. 43, no. 4, pp. 1199-1213, 2000.

- Kuddus A and Rahman A. Human Rights Abuse: A Case Study on Child Labor in Bangladesh. International Journal of Management and Humanities 2015; 1(8): 1-4.

- M. Black, Children First: The Story of UNICEF, Past and Present. USA: Oxford University Press, pp. 119-147, 1996.

- Kamruzzaman M and Hakim M. A. (2015). Socio-economic Status of Child Beggars in Dhaka City.Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities,1 (5): 516-520.

- Kamruzzaman M and Hakim M A. Socio-economic Status of Slum Dwellers: An Empirical Study on the Capital City of Bangladesh, American Journal of Business and Society2016, 1(2): 13-18.

- Islam MS, Hakim M A, Kamruzzaman M, Safeuzzaman, Haque MS, Alam MK. Socioeconomic Profile and Health Status of Rickshaw Pullers in Rural Bangladesh.American Journal of Food Science and Health 2016, 2(4):32-38.

- Hakim, M. A. and Kamruzzaman, M. (2015). Nutritional Status of Preschoolers in Four Selected Fisher Communities. American Journal of Life Sciences, 3 (4): 332-336.

- Rahman, A, Chowdhury, S., Karim, A. and Ahmed, S. (2008). Factors associated with nutritional status of Children in Bangladesh: A multivariate analysis. Demography India, 37 (1): 95-109.

- Hakim, M. A., Talukder, M. J. and Islam, M.S. (2015). Nutritional Status and Hygiene Behavior of Government Primary School Kids in Central Bangladesh. Science Journal of Public Health, 3 (5): 638-642.

- National Report of Bangladesh on ‘Global Study on Child Poverty and Disparities’; UNICEF, 2009.

- Hakim, M. A. and Kamruzzaman, M. (2015). Nutritional Status of Central Bangladesh Street Children. American Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Research, 2 (5): 133-137.

- Hakim MA. Nutrition on malnutrition helm, nutrition policy in fool's paradise.Available at http://www.observerbd.com/2015/09/20/111732.php (Accessed on September 20, 2015).

- Flowers (2010). pp. 20-21.

- Kamruzzaman, M. and Hakim, M. A. (2015). Family Planning Practices among Married Women attending Primary Health Care Centers in Bangladesh. International Journal of Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering, 1 (3): 251-255.

- Kamruzzaman M and Hakim M A. Condom Using Prevalence and Phobia on Sexually Transmitted Diseases Among Sex-Buyers in Bangladesh, American Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health2016, 1(1): 1-5.

- Evgenia Berezina (1997). Victimization and Abuse of Street Children Worldwide. Youth Advocate Program International Resource Paper, Yapi. Retrieved November 30, 2012.

- Kamruzzaman, M., Hakim, M. A. (2015). Child Criminalization at Slum Areas in Dhaka City. American Journal of Psychology and Cognitive Science,1(4): 107-111.

- Rahman, A. and Biswas, S.C. (2009). Nutritional status of under-5 children in Bangladesh. South Asian Journal of Population and Health 2(1), pp. 1-11.

- Rahman, A. and Chowdhury, S. (2007). Determinants of chronic malnutrition among preschool children in Bangladesh, Journal of Biosocial Science, 39(2):161-173.

- Kamruzzaman M. (2015). Child Victimization at Working Places in Bangladesh, Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities;1(5): 516-520.

- T. Islam, M. M. Haque and S. R. Tarik, Developing Skill and Improving Environment of the Street Children at Aricha and Daulatdia Ferry Ghats. Mohammadpur: ACLAB, pp.10-11, 2001.

- Kamruzzaman M. Dowry related Violence against Rural Women in Bangladesh. American Journal of Psychology and Cognitive Science 2015; 1(4): 112-116.

- Hai, M. A. (2014). Problems Faced By the Street Children: A Study on Some Selected Places in Dhaka City, Bangladesh. International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research, 3(10): 45-56.

- Rahman, A. and Harding, A. (2010). Some health related issues in Australia and methodologies for estimating small area health related characteristics, Online Working Paper Series: WP-15, NATSEM, University of Canberra, p. 1-59.

- Sumon, A. I. Informal Economy in Dhaka City: Automobile Workshop and Hazardous Child Labor. Pakistan Journal of Social Sciences2007; 4(6): 711-720.

- Kattel E, Jan K, Erik R (2009). Ragnar Nurke (1907-2007), Anthem Press, p. 786-9.

- Rahman, A. and Kuddus, A. (2014), A new model to study on physical behavior among susceptible infective removal population, Far East Journal ofTheoretical Statistics, 46(2), p. 115-135.

- Megabiaw B, and Rahman A. (2013) Prevalence and determinants of chronic malnutrition among under-5 children in Ethiopia. International Journal of ChildHealth and Nutrition, 2(3), p. 230-236.

- Rahman, A. and Sapkota, M. (2014), Knowledge on vitamin A rich foods among mothers of preschool children in Nepal: impacts on public health and policy concerns, Science Journal of Public Health, 2(4), p. 316-322.

- Kamruzzaman, M and Hakim MA. Livelihood Status of Fishing Community of Dhaleshwari River in Central Bangladesh.International Journal of Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering,2(1): 25-29.

- Bangladesh Bureau Statistics (BBS) (2003). Child labor in Bangladesh.

- Ahmed F and Islam MA. Dietary pattern and nutritional status of Bangladeshi manual workers (rickshaw pullers). International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition 1997; 48(5): 285-291.

- Nazrul I. Sociological perspective of poverty. Bangladesh e-journal of sociology 2010; 7(2): 57-60.

- Rahman A and Hakim MA. Malnutrition Prevalence and Health Practices of Homeless Children: A Cross-Sectional Study in Bangladesh. Science Journal of Public Health 2016; 4 (1-1): 10-15.

- Sharmin AS (2008). Hygiene promotes teach safe sanitation practices in Bangladesh.

- Hoque MM, Arafat Y, Roy SK, Khan SK et al. Nutritional Status and Hygiene Practices of Primary School Children. J Nutr Health Food Engg 2014; 1(2): 00007.

- ICDDR, B (2010) Street dwellers performance for health care services in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Dhaka: ICDDR, B.

- Bhandari S and Banjara MR. Micronutrients Deficiency, a Hidden Hunger in Nepal: Prevalence, Causes, Consequences, and Solutions. International Scholarly Research Notices Volume 2015(2015, Article ID 276469, 9 pages.

- Bulbul T and Hoque M. Prevalence of childhood obesity and overweight in Bangladesh: findings from a countrywide epidemiological study. BMC Pediatr 2014; 14: 86.

- UNICEF, ILO, World Bank Group (2009). Understanding Children’s Work in Bangladesh.

- UNICEF (2008). Opinions of children of Bangladesh on corporal punishment.

- L. Aptekar. Street Children in the Developing World: A Review of Their Conditions, Cross-Cultural Research, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 195-224, 1994.

- Kolosov.‘The Rights of the Child’, Janusz Symonides (ed), Human Rights: Concepts and Standards, Rawat, Jaipur, 2002.

- Tripathi, S. C. and Arora, Vibha (2010), Law Relating to Women and Children, Allahabad: Central Law Publications.

- Rai, Rahul (2000), Human Rights: U N Initiatives, Delhi: Authors Press, Delhi.

- Rabiul H. (2009) "A Baseline Study on Situation of Child Labor and Potential to be Child Labour among Children with Disabilities". Centre for Services and Information on Disability (CSID).

- Bangladesh population census and Labor force survey (1974). Child labor in Bangladesh: trends, patterns and policy.

- Kamruzzaman M and Hakim M A.Prostitution Going Spiral: The Myth of Commercial Child Sex.International Journal of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences 2016, 1(1): 1-6.

- ILO (2013) Working out of poverty. International labor office, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Kamruzzaman M et al. Patterns of Behavioural Changes Among Adolescent Smokers: An Empirical Study.Frontiers in Biomedical Sciences 2016, 1(1): 1-6.

- United Nation (2012). How would empowering people help achieve poverty eradication? United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Islam, J., Quazi, A. and Rahman, A. (2011), Nexus between cultural dissonance, management accounting systems and managerial effectiveness: Evidence from an Asian developing country, Journal of Asia Pacific Business, 12(3): 280-303.

- Kamruzzaman M.A Criminological Study on the Dark Figure of Crime as a Socio-ecological Bulk of Victimization. American Journal of Business, Economics and Management2016,4(4): 35-39.

- Kamruzzaman M and Hakim M A. Factors Associated with the Suicidal Tsunami as a Mental Illness: Findings from an Epidemiological Study.American Journal of Environment and Sustainable Development 2016, 1(1):1-5.

- P. Kellett and J. Moore. Routes to Home: Homelessness and Home-making in Contrasting Societies, Habitat International 2003; 27: 123-141.

- Hasan R. (2009) A Baseline Study on Situation of Child Labour and Potential to be Child Labour among Children with Disabilities. Centre for Services and Information on Disability CSID), Dhaka.

- Das SK, Khan M B U and Kamruzzaman M.Preventive Detention and Section 54 of the Code of Criminal Procedure: The Violation of Human Rights in Bangladesh.American Journal of Business and Society 2016, 1(3): 60-67.

- Shabnam N, Faruk MO and Kamruzzaman M.Underlying Causes of Cyber-Criminality and Victimization: An Empirical Study on Students. Social Sciences2016, 5(1): 1-6.

- Plan Bangladesh. Child Protection Policy -Say No to Child Abuse: Plan‘s Policy to Child Protection, 1 January 2005. Dhaka: Plan Bangladesh, 2005.

- White B. Globalization and the Child Labour Problem. Journal of International Development 1996; 8(6): 829-839.