Vocal Variability and Dialect Forms of Chaffinch Song (Fringilla coelebs L.) in the European Russia

O. A. Astakhova*

Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Faculty of Biology, Moscow State University of M. V. Lomonosov, Russia

Abstract

Songs of birds can be as analogy of human speech. Thus to territorial distribution of song patterns frequently call as dialects. Changes of vocalization structure (songs, calls) of birds are known phenomenon in the bioacoustics. But formation of dialect song forms of many bird’s species are not found. In the article variants of song types of chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs L.) are presented.

Keywords

Birds Song, Species-Specific Song, Dialects of Song

Received: March 5, 2015 / Accepted: March 21, 2015 / Published online: May 11, 2015

@ 2015 The Authors. Published by American Institute of Science. This Open Access article is under the CC BY-NC license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

1. Introduction

Geographical variability of song at many species of birds has been marked as a phenomenon of differentiation of song structures or song patterns (as the image on sonograms) in different local populations (Marler, 1952; Marler, Tamura, 1962; Sick, 1939; Poulsen, 1951). Local variants of vocalizations of birds can be considered as analogy of human speech and to name as dialects. Borders of a dialect define lexical (word structure), morphological (an accent, structure) and phonetic (pronunciation) characteristics of the dictionary (Kurath, 1972).

Song dialect of birds is a variant of the traditional form of song, shared by members of a local population of birds and it forming borders of a dialect (separating from other variant of song pattern), within the limits of which there is a traditional training (song learning) of characteristic song components in the given population. But thus big song repertoires of some species of sparrow birds interfere (have problem) with objective definition of dialect borders (Thielcke, 1969; Kreutzer, 1974; Kroodsma, 1974; Baker, 1975; Baptista, 1975; Lemon, 1975; Payne, 1981; Mundinger, 1980, 1982).

Chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs L.) is classical object of study of becoming of vocal repertoire (Thorpe, 1958; Marler, 1956; Nottebohm, 1967) and of geographical variability of species-specific song in a population (Promptov, 1930; Sick, 1939; Thielcke, 1961; Simkin, 1983; Slater et al., 1984).

Regional variability of song can be determined in qualitative aspect (the form of a syllable, syntax) and quantitative (time-and-frequency) parameters. The concept of a dialect should be closely (cautiously) and is carefully argued at establishment of regional variability of call (voice) and of song patterns.

2. Material and Methods

The problem of our researches is revealing of macrogeographical distinctions of chaffinch song (Fringilla coelebs L.) in different local populations, which are removed approximately on 1000 km from each other. In northwest (Curonian spit, the Kaliningrad region) and in central parts (Zvenigorod, Moscow, Michurinsk) of the European Russia have been made tape records of singing males (N=218) during the spring-and-summer period of 2005-2006.

Sonograms of types of songs have been analyzed with the help of computer program Avisoft SASLab Light. In total have been analyzed about five thousand songs. Types of songs have been marked by Latin letters. At record, songs of one type have been met in different points of territory (considered that belong to repertoires of different males), therefore alongside with the letter have been designated by numbers in ascending order (for example, А1, А2, А3, etc.).

For record of songs have been used tape recorder Panasonic RQ-SX95F, condenser microphone Philips SBC ME570. To territorial distribution of individuals has been applied group approach (Simkin, 1983) and in parallel - points of record have been marked on map.

At the analysis of song sonograms of chaffinch basically have been applied two qualitative methods: revealing (detection) of phonetic distinctions (frequency of a sound, its form on sonogram) or of ways of a pronunciation of syllables of the phrases making songs; revealing of lexical distinctions (changes of phrases of songs as a whole) (Mundinger, 1982).

Also have been spent the quantitative analysis of dialect forms of songs of one type and comparison of their basic time-and-frequency parameters (duration of songs - sec, number of elements in song type, duration of syllables in started singing, trills, in final stroke, the maximal, minimal and average frequency of songs - KHz, intervals between songs -sec).

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Dialect Forms of Song

In populations of the central part of the European Russia (N=65 of males) we allocate (distinguish) 15 types of song of chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs L.), which have been completely similar in structure or have been in part modified in the syllabic form (on sonograms) in comparison with songs of same types in samples of a northwest part of the European Russia (N=153 of males). For seven types of song from twenty two (tests on Curonian spit) analogies (similarities) have not come to light – probably, owing to their rarity. Many song types in the central part of the European Russia have been considered as combined phrases (parts) of syllabic patterns known to us, but frequently with the changed figure (forms) on sonogram.

In result, have been found 12 dialect forms of songs of one type, which appeared similar in base structure of elements, of phrases, but in different regions of Russia frequently had distinguished manners, ways of their performance at singing (phonetic aspect). The average size of chaffinch repertoire (Fringilla coelebs L.) in populations of the central part of the European Russia from statistical calculations has been submitted 1,93 ± 0,22 types of song (max – 4 types of song, min – 1 song type) at a capture (volume) on the average 24,7 ± 11,3 songs from one of male.

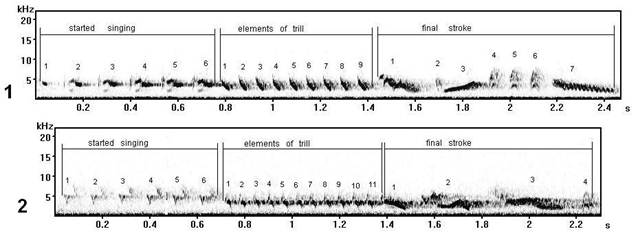

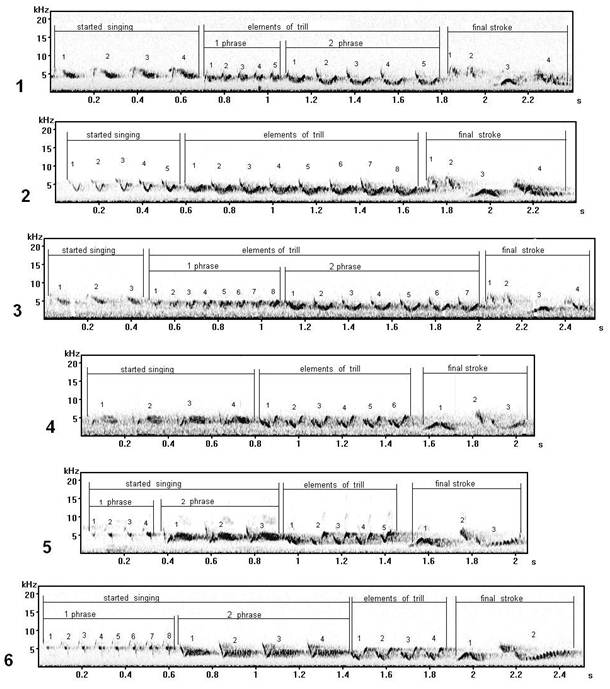

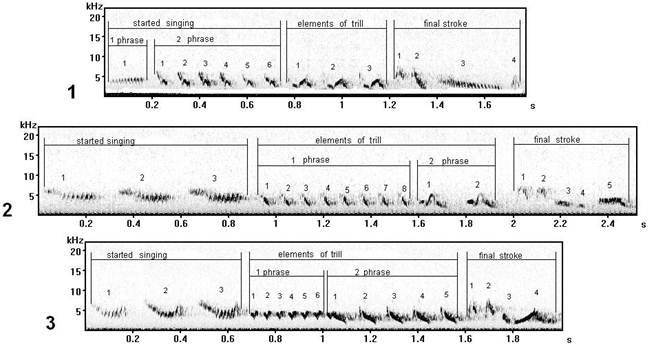

As a bright example of vocal variability of chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs L.) it is possible to result (to show) some local variants of songs, which we have attributed to one type (fig. 1). Samples of types of song, which will be resulted (be shown), were not single in a population and have been recorded in repertoires more, than 1-2 individuals.

In the figure 1 and 2 there are phonetic components of a dialect, which characterize style of singing (song culture) in a local population on the given song type - in the started singing (whistle elements), in trill of songs and in the final stroke.

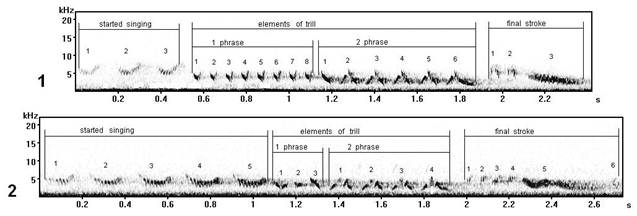

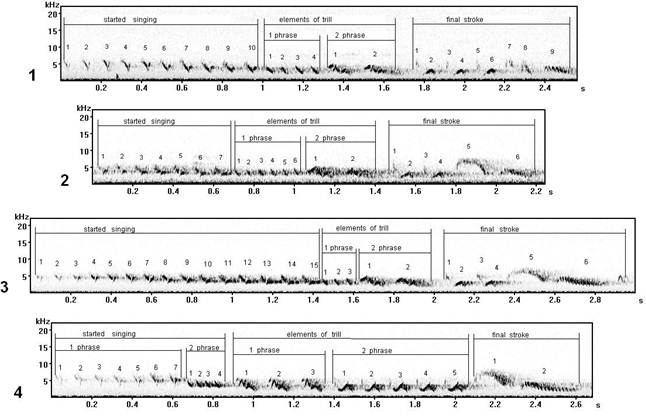

In the samples also types of song have been found, which are difficult for differentiating among themselves because of their similarity (fig. 3). We have attributed the given samples of songs to different song types (D, F, G), but nevertheless they are similar among themselves in base structure of elements (especially in the started singing and trill), which nevertheless are performance at singing by different manners (ways), that makes their distinct or different. Probably, it – the initial forms of the further modification, and it represent insignificantly transformed forms for precise revealing of type to which are attributed.

Table 1. Vocal variability of chaffinch songs (Fringilla coelebs L.) in populations of the European part of Russia (N = 218) *

| Vocal variability | Song type (token) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | I | H | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | V | W | U | Total | |

| Dialects1 | + | + | + | + | + | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Subdialects2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 7 | ||||||||||||||||

| European part of Russia | Sample size of song type (n) in population | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Northwest | 18 | 5 | 38 | 11 | 7 | 16 | 10 | 22 | 6 | 13 | 3 | 1 | 20 | 8 | 18 | 1 | 1 | 24 | 17 | 14 | 2 | 8 | 183 | |

| Center | 8 | 8 | 24 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 11 | 12 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 93 | |||||||||

The note: 1dialects – different phonetic norms of song types; 2subdialects – small phonetic distinctions of song types; * - sample size of chaffinch males (Fringilla coelebs L.) at record; the most widespread (frequently met) in populations types of songs (with sample n> 15) are allocated (signed) by a font.

Table 2. The basic time-and-frequency parameters of song type B (fig. 5).

| Variants of song type | Number of songs (n) | Place of record | The length of song, sec | Min frequency, КHz | Max frequency, КHz | Median (average) frequency, КHz | Number of syllables in song type | Length of syllables in started singing, sec | Length of syllables in trill, sec * | Length of syllables in final stroke, sec | Intervals between songs, sec | |

| 1 phrase | 2 phrase | |||||||||||

| В5 | 8 | Curonian spit (Kaliningrad region) | 2,47 ±0,104 | 1,57 ±0,14 | 7,19 ±0,32 | 3,77 ±0,14 | 24,5 ±0,93 | 0,056 ±0,003 | 0,043 ±0,003 | 0,14 ±0,01 | 0,06 ±0,007 | 5,32 ±1,9 |

| В | 4 | Zvenigorod (Moscow region) | 2,48 ±0,36 | 1,68 ±0,16 | 7,92 ±0,31 | 3,83 ±0,36 | 22,25 ±2,99 | 0,073 ±0,005 | 0,04 ±0,003 | 0,17 ±0,008 | 0,075 ±0,018 | |

| В8 | 10 | Michurinsk (Tambov region) | 2,34 ±0,15 | 1,62 ±0,09 | 8,044 ±0,53 | 4,12 ±0,29 | 22,3 ±2,6 | 0,068 ±0,003 | 0,034 ±0,006 | 0,127 ±0,013 | 0,09 ±0,016 | 4,3 ±0,59 |

| В7 | 10 | Michurinsk (Tambov region) | 2,99 ±0,11 | 1,67 ±0,08 | 7,63 ±0,08 | 3,79 ±0,18 | 27,4 ±1,17 | 0,05 ±0,005 | 0,033 ±0,003 | 0,15 ±0,007 | 0,084 ±0,022 | 7,06 ±0,19 |

The note: average value and a standard deviation of parameters of song types from statistical calculations for all songs of one type which were reproduced of males chaffinch in the given points of record are specified; the strongest differences counted a difference of parameters >0,5 КHz in frequency and >0,02 sec in length (are allocated or distinguish by a font); * - the trill of song type B will consist of two phrases.

Table 3. The basic time-and-frequency parameters of song type С (fig. 6).

| Variants of song type | Number of songs (n) | Place of record | The length of song, sec | Min frequency, КHz | Max frequency, КHz | Median (average) frequency, КHz | Number of syllables in song type | Length of syllables in started singing, sec | Length of syllables in trill, sec * | Length of syllables in final stroke, sec | Intervals between songs, sec | |

| 1 phrase | 2 phrase | |||||||||||

| С3 | 20 | Curonian spit | 2,074 ±0,118 | 1,627 ±0,131 | 9,698 ±0,41 | 4,0996 ±0,173 | 17,25 ±0,85 | 0,1203 ±0,005 | 0,068 ±0,003 | 0,1155 ±0,008 | 0,071 ±0,005 | 6,423 ±1,9 |

| С3 | 15 | Zvenigorod (Moscow region) | 2,59 ±0,16 | 1,73 ±0,23 | 8,15 ±0,51 | 3,93 ±0,23 | 18,7 ±0,9 | 0,15 ±0,007 | 0,052 ±0,005 | 0,15 ±0,034 | 0,1 ±0,014 | 10,06 ±1,7 |

| С21 | 3 | Michurinsk (Tambov region) | 2,98 ±0,15 | 2,01 ±0,36 | 7,5 ±0,7 | 4,02 ±0,2 | 22 ±1,41 | 0,13 ±0,01 | 0,048 ±0,007 | 0,12 ±0,015 | 0,084 ±0,005 | 6,05 ±5,17 |

| С7 | 4 | Moscow | 2,24 ±0,2 | 1,68 ±0,16 | 9,39 ±0,1 | 4,44 ±0,17 | 16,25 ±1,89 | 0,14 ±0,008 | 0,06 ±0,003 | 0,15 ±0,004 | 0,1 ±0,076 | 8,8 ±5,66 |

| С#11 | 3 | Moscow | 2,73 ±0,3 | 1,78 ±0,1 | 8,096 ±0,6 | 4,54 ±0,43 | 20 ±1,73 | 0,22 ±0,006 | 0,076 ±0,003 | 0,12 ±0 | 0,081 ±0,019 | 8,26 |

| Cо4 | 10 | Zvenigorod (Moscow region) | 2,39 ±0,12 | 1,41 ±0,1 | 7,75 ±0,24 | 4,48 ±0,21 | 12,3 ±0,48 | 0,21 ±0,03 | - | 0,12 ±0,01 | 0,1 ±0,085 | 6,54 |

| C*11 | 2 | Curonian spit | 2,55 ±0,082 | 1,3 ±0,37 | 7,751 ±0 | 4,478 ±0 | 19 ±1,4 | 0,175 ±0,007 | 0,034 ±0,01 | 0,084 ±0,001 | 0,0915 ±0,002 | 22,9 |

The note: average value and a standard deviation of parameters of song types from statistical calculations for all songs of one type which were reproduced of males chaffinch in the given points of record are specified; the strongest differences counted a difference of parameters >0,5 КHz in frequency and >0,02 sec in length (are allocated or distinguish by a font); * - the trill of song type С will consist of two phrases.

Fig. 1. Dialect of song type V: 1 - song type V 1 (record on Curonian spit, the Kaliningrad region); 2 – song type V (record in Zvenigorod, the Moscow region).

Fig. 2. Dialect of song type S: 1 – song type S5 (record on Curonian spit, the Kaliningrad region); 2 – song type S (record in Zvenigorod, the Moscow region).

Fig. 3. Similar types of chaffinch songs (record on Curonian spit, the Kaliningrad region): 1 – song type D3; 2 – song type F4; 3 – song type G3.

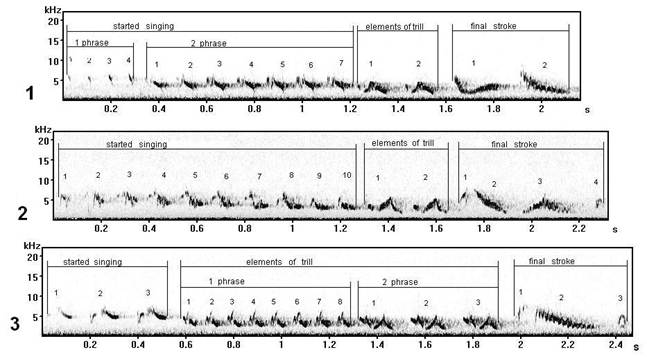

The song type J is difficult for the analysis because its structure can be various both in one local population, and in different regions. The started singing frequently is made by the phrase of "V-shape" elements with the subsequent powerful subelements in force of a sound. In a trill usually large "arc-similar" elements (hardly differ on structure in northwest and in the center of the European Russia), before it there can be a phrase of thin elements - it is sometimes are heard as started singing (fig. 4.2). Probably, the features of structure of elements marked by us reveal dialect forms of song type J in phonetics of a trill and of a final stroke.

Fig. 4. Variants of song type J: 1 – song type J10 and 2 – song type J (record on Curonian spit, the Kaliningrad region); 3 – song type J (record in Zvenigorod, the Moscow region); 4 – song type J3 and 5 – song type J8 (record in Moscow); 6 – song type J12 (record in Michurinsk, the Tambov region).

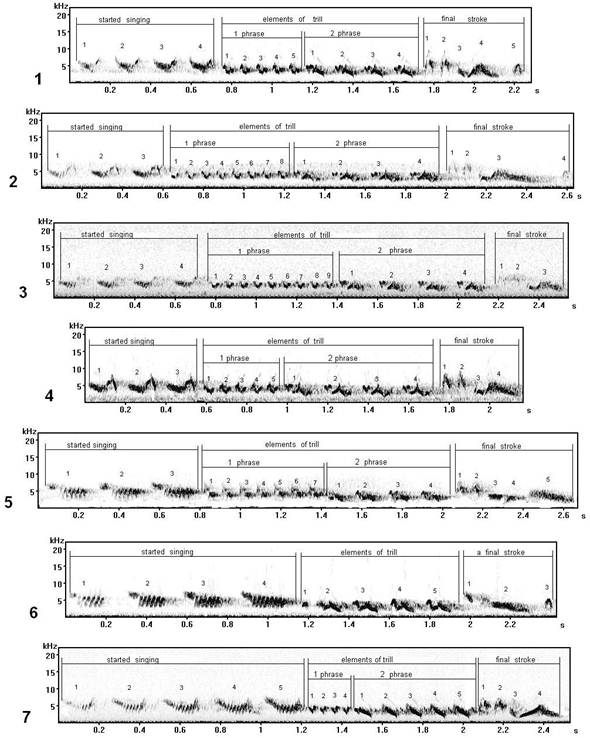

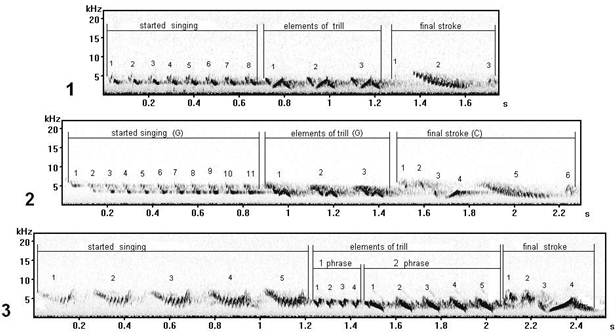

Fig. 5. Variants of song type B: 1 – song type В5 (record on Curonian spit, the Kaliningrad region); 2 – song type B (record in Zvenigorod, the Moscow region); 3 – song type В8 and 4 – song type В7 (record in Michurinsk, the Tambov region).

Despite of stability in a manner of performance of song type B, in different local populations on sonograms it is possible to note some variability of the final stroke (in the latter case (fig. 5.4) the number of the first elements of a stroke is increased, and the phrase is heard as a trill). In different areas of the European Russia penultimate elements of the final stroke differ: in northwest (fig. 5.1) they such as two arches (7, 8), and in the central part (fig. 5.2, 5.3, 5.4) are submitted by one big arch (5). Probably, given phonetic distinction (concerning to features of a pronunciation of elements, their forms, frequency on sonogram) of syllables of the final stroke is components of a dialect (local song cultures).

3.2. Character of Vocal Variability of Chaffinch Songs

At the quantitative analysis of local variants of song type B come to light some distinctions (differences) in values of the basic time-and-frequency parameters, but in the majority they are similar (tab. 2).

From results of comparison of parameters of song type B it is visible (tab. 2), that the length of songs, number of their syllables, the maximal frequency, intervals between songs and length of elements of the second phrase of a trill have the values varying in wide enough range, frequently even beyond the insignificant difference established by us (differences are allocated or signed by a font). It is necessary to note, that the minimal frequency and length of syllables of the first phrase of a trill of songs of type B are appeared completely similar as in northwest (Curonian spit), and in the center of the European Russia (Zvenigorod, Michurinsk).

For chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs L.) typically selective training (song learning) of species specific song in sensitive (perceiving) period (Marler, 1956; Thorpe, 1958; Nottebohm, 1967). Therefore young birds do not learn songs of other species, and they are guided by a time-and-frequency range of songs of the own species. Probably, as a result of such rigid genetic determination of species specific song (Simkin, 1983) is observed small variability of the basic time-and-frequency parameters of its different dialect forms (even at the account of a wide variation of values).

By full dialect of chaffinch song (Fringilla coelebs L.) in the certain territory it would be more correct to account the presence of dialect forms on all song types known to us in a population (originally 22 song types have been found), that, likely, it is almost impossible because of limitation of a sample of songs and constant mixing of vocal traditions of birds in different populations as a result of migrations (Slater, Ince, 1979, 1980; Espmark et al., 1989).

Song type C (fig. 6) is the most widespread in all areas of the European Russia investigated by us. Probably, therefore the given song type has some updating (modifications, variants) in a manner of execution (performance) of phrases at singing. Nevertheless, all these variants of songs on hearing are perceived as similar: the started singing – as a number (line, row) of sharp (sometimes gnash or creaking) whistle sounds ("fuit-fuit-fuit"), a trill consist of two phrases – the first phrase is heard as a number (line) of more thin sounds, the second phrase – tone of a trill is more powerful ("til-til-til* tel-tel"), a final stroke - is short sharp rise and recession of a sound ("chi-kuik").

Fig. 6. Variants of song type C: 1 – song type С3 (record on Curonian spit, the Kaliningrad region); 2 – song type С3 and 6 – song type Со4 (record in Zvenigorod, the Moscow region); 3 – song type С21 (record in Michurinsk, the Tambov region); 4 – song type С7, 5 – song type C#11 (record in Moscow); 7 – song type С*11 (record on Curonian spit, the Kaliningrad region).

Whether it is possible these three forms of song type C (C, C#, C*) to account as dialect forms, even if they meet in one territory (for example, С7 and C#11 recorded in Moscow (fig. 6.4, 6.5), С3 and С*11 (fig. 6.1, 6.7) recorded on Curonian spit) – a complex (difficult) question. What origin of these variations (variants) of songs of one type – by wrong (incorrect) learning of birds and by further fastening of these songs in a population by training (song learning) of the following generations, or it is result of "introduction" of songs of migrants in local song culture - also it is possible to assume only. In Zvenigorod (the Moscow region) and Michurinsk (the Tambov region) there was a simplified variant of song type C (C0) (fig. 6.6) without the first phrase of a trill and having the simplified final stroke. Probably, it is result of improvisation at singing.

At comparison of the basic time-and-frequency parameters of local variants of song type C (tab. 3) the greatest difference had values of length of songs, the maximal frequency, number of syllables in song types, intervals between songs at singing (these parameters included rather wide range of distribution of the data). In other parameters (the minimal, average frequency, length of elements of a trill) come to light (are revealed) the most distinguished values (are allocated or signed by a font), but relative uniformity of the data nevertheless is observed.

Thus, similarity (in view of a variation of values in the certain range) of the basic time-and-frequency parameters of song type C (at presence of dialect forms) also can confirm their importance in transfer and maintenance (keeping, memory) of song traditions at chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs L.) in different populations of an area of distribution of this species.

3.3. Combined (Mixed) Song Types

Many types of chaffinch song (Fringilla coelebs L.) in samples of the central part of the European Russia were considered by us as combined phrases of already known types of the song, which have been recorded on Curonian spit (the Kaliningrad region), but their elements have been modified on sonograms. It is possible to result (to show) some examples.

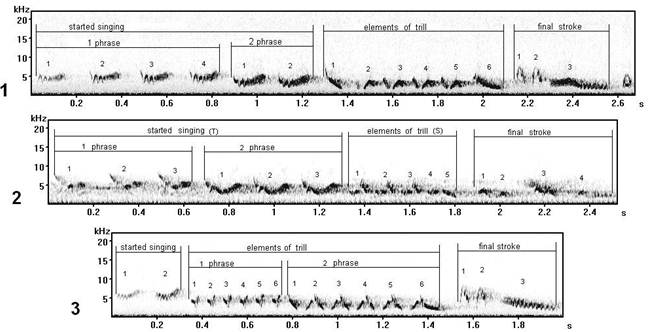

Fig. 7. Dialect phrases of song types Т and S: 1 – song type Т (record on Curonian spit, the Kaliningrad region); 2 - the combined song type ТS (record in Michurinsk, the Tambov region); song type S (record on Curonian spit, the Kaliningrad region).

Trill elements of song type TS (fig. 7.2) that also met in samples of the center of the European Russia are similar to trill of song type S (fig. 7.3.) and to started singing and to trill of song type Т (fig. 7.1) from a population on Curonian spit (but it is more similar – to a trill such as type S).

The started singing (whistle elements) and trill elements (the first phrase) of song type CМ 2 (fig. 8.2) are similar to song type С* (fig. 8.3) (to started singing and to the second phrase of a trill of "stick-similar" syllables). Elements of the second phrase of a trill of song type CM 2 are almost identical with a trill of song type M (fig. 8.1). The final stroke of song type CM has the general (common) structure both to song type M, and to song type С* (last element of which by "triangular" form, but it is not divided in subelements).

The started singing (whistle elements) and the trill of the combined song type GC (fig. 9.2) is similar to starting singing and to the trill of song type G (fig. 9.1), and the final stroke - similar to the final of song type С* (fig. 9.3) (but last element of this stroke of type GC hardly is separated on subelements).

Thus, in samples of different areas of Russia there can be the types of song combined from phrases of song patterns of other populations, but including the modified elements - it is possible to tell, their dialect forms. In samples of the central part of the European Russia the songs have been found which include phrases at once of two-three different types of song from other population of chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs L.) in the northwest of the European Russia. These phrases had a lot of similar in structure of elements, but nevertheless they differed in a manner of their execution (performance) at singing. If such songs of one type having the changed elements have the majority of individuals in a population, it is possible to assume about existence certain (determined) song cultures in these song types or in separate phrases.

Fig. 8. A combination of the dialect phrases: 1 – song type М2 (record on Curonian spit, the Kaliningrad region); 2 - the combined song type СM 2 (record in Michurinsk, the Tambov region); 3 – song type С*13 (record on Curonian spit, the Kaliningrad region). +

4. Conclusions

Many characteristics of singing of birds are precisely mentioned by social training traditions receiving their vocal patterns by species-specific imitation. Therefore the tradition, custom should be taken into account at the analysis of geographical variability of vocal behaviour.

In local populations are formed certain song cultures that are capable to change during time and can to make dialect forms on all area of distribution of a species. Steady song dialects during time – the phenomenon of conservatism of the vocal traditions, transmitted to the subsequent generations by means of vocal imitation. For many species the patterns of variability as purchases (changes) of vocal traditions are a product (result) of cultural evolution (Mundinger, 1980). Cultural evolution is a parameter for species with a historical variety of patterns of microgeographical variability, and also for species with differentiated syllables. But it is not a parameter in morphological variability (Lemon, 1975; Slater and Ince, 1979).

It is possible to allocate (to sign) 3 steps of vocal variability (by way of reduction of scale of a category) (Mundinger, 1982):

1. Vocal norms (installation) (song institute) – regional populations of lexical variants;

2. Dialects represent local populations of the phonetic variants limited by the main ''isophone bundles'' (set of different phonetic norms);

3. Subdialects are the next or neighbour (close to each other) populations of phonetic variants having small set of isophone (that is a small variety of forms).

We made song samples in different regions of the European Russia (northwest and the central part), it is possible to draw a conclusion that in some song types of chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs L.) exist subdialects (insignificant phonetic distinctions of syllables) – for example, on song types B, M, D, G, V, S, U, and dialects (different phonetic norms of types of song) – C, C# and C*, F, I, J, N, and there are also stable types of song (in samples of different regions are invariable) – song type A.

Vocal norms (installations), likely, can be judged by quantity of individuals in a population that adhere to those or others song cultures (ways of singing) of different song types. If the majority of males sing any song type such certain style (special manner of performance), then it is will be vocal norm (installation) in the given song type (or in type of a phrase) in the given population. But it is difficult to define vocal norms of a population at repertoires of great volume (when song types much) (Kroodsma, 1974). Thus, in twelve types of song at chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs L.) the dialect forms (B C D F G I J M N V S U) have been found. It is interesting to note, that the dialect forms of songs or separate phrases (in the "combined" songs) of one type can have been met within the limits of one local population.

The basic time-and-frequency parameters of local variants of song types of chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs L.) at the quantitative analysis had insignificant macrogeographical variability that can speak about their importance in transfer and maintenance (keeping, memory) of specific song traditions of this species. The most stable parameters of local variants of songs of one type are appeared minimal and average (median) frequency (KHz), values of length (sec) and intervals of elements of a trill (sec).

Fig. 9. Dialect phrases of song types G and C: 1 – song type G6 (record on Curonian spit, the Kaliningrad region); 2 – song type GC (record in Michurinsk, the Tambov region); 3 – song type С*11 (record on Curonian spit, the Kaliningrad region).

Acknowledgement

Authors express sincere gratitude for the help in gathering a field material to employees of biological station of Curonian spit and of Zvenigorod biological research station of the Moscow State University.

References

- Baker M. C. 1975. Song dialects and genetic differences in White-crowned Sparrows (Zonotrichia leucophrys) // Evolution. № 29. P. 226-241.

- Baptista L. F., King J. R. 1980. Geographical variation song and dialects of montane white-crowned sparrows // Condor. № 79. P. 356-370.

- Espmark Y. O., Lampe H. M., Bjerke T. K. 1989. Song conformity and continuity in song dialects of redwings Turdus iliacus and some ecological correlates // Ornis Scand.1989. № 20. P. 1-12.

- Kreutzer M. 1974. Stereotypie et varianttions dans les chants de proclamation territoriale chez le Troglodyte (Troglodytes troglodytes) // Rev. Comp.Anim. № 8. P. 270-286.

- Kroodsma D. E. 1974. Song learning, dialects, and dispersal in the Bewick`s Wren // Tierpsychol. № 35. P. 352-380.

- Kurath H. 1972. Studies in Areal Linguistics. Bloomington. Indiana University Press. 127 p.

- Lemon L. E. 1975. How birds develop song dialects // Condor. № 77. P. 385-406.

- Marler P. 1952. Variation in the song of the Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs // Ibis. № 94. P. 458-472.

- Marler P. 1956b. The voice of the chaffinch and its function as a language // Ibis. № 98. P. 231-261.

- Marler P., Tamura M. 1962. Song dialects in three populations of White-crowned Sparrows // Condor. № 64. P. 368-377.

- Mundinger P. C. 1980. Animal cultures and a general theory of cultural evolution // Ethol. Sociobiol. № 1. P. 183-223.

- Mundinger P. C. 1982. Microgeographic and macrogeographic variation in acquired vocalizations of birds // Acoustic communication in birds / Eds. D.E. Kroodsma, E.H. Miller. New York. P. 147-208.

- Nottebohm F. 1967. The role of sensory feedback in development of avian vocalizations // Proc. Int. Ornithol. Cong. 14. Oxford-Еdinburg: Blackwell scient. Publs. P. 265-280.

- Payne R. B. 1981. Population structure and social behavior: models for testing ecological significance of song dialects in birds. In "Natural Selection and Social Behavior: Recent Research and New Theory" / Eds R.D. Alexander, D.W. Tinkle. New York, Chiron. P. 108-119.

- Poulsen H. 1951. Inheritance and leaning in the song of the Chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs) // Behaviour. № 3. P. 216-228.

- Promptov A. N. 1930. Geographical variability of chaffinch song in connection with the common questions of seasonal flights of birds // Zool. journ. № 10 (3): 17-40.

- Simkin G. N. 1972. About biological value of bird singing // The Bulletin of the Moscow university. № 1. Moscow: 34-43.

- Simkin G. N. 1983. The typological organization and population phylogeny of bird’s songs // Bulletin of Moscow community investigators of nature. Section of biology. V. 88. № 1. Moscow: 15-27.

- Slater P. J. B., Ince S. A. 1979. Cultural evolution in chaffinch song // Behaviour. № 71. P. 146-166.

- Slater P. J., Ince S. A., Colgan P. W. 1980. Chaffinch song types: their frequencies in the population and distribution between repertoires of different individuals // Behaviour. № 75. P. 207-218.

- Slater P. J. B., Clement F. A., Goodfellow D. J. 1984. Local and regional variations in chaffinch song and the question of dialects // Behaviour. № 88. P. 76-97.

- Sick H. 1939. Ueber die Dialektbildung beirn Regenruf des Buchfinken // J. Ornit. № 87. P. 568-592.

- Thielcke G. 1961. Stammesgeschichte und geographische Variation des Gesanges unserer Baumläufer // Verh Ornithol. Ges Bayern. № 14. P. 39-74.

- Thielcke G. 1969. Geographic variation in bird vocalizations // Bird Vocalizations / Eds. R.A. Hinde. London, New York. P. 311-340.

- Thorpe W. H. 1958. The leaning of song patterns by birds, with especial reference to the song chaffinch Fringilla coelebs // Ibis. № 100. P. 535-570.